This article is in the Featured Author and Interviews Categories

An Interview with Costa Book Award winner author Manjeet Mann

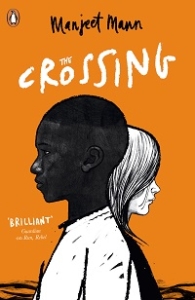

Manjeet Mann has won the 2022 Costa Children’s Book Award with her second verse novel, The Crossing; a profound story of hope, grief, and the very real tragedies of the refugee crisis. Manjeet talked to Charlotte Hacking about what inspired the story, the real stories beyond the pages, and why writing for young adults is so important to her.

Manjeet Mann has won the 2022 Costa Children’s Book Award with her second verse novel, The Crossing; a profound story of hope, grief, and the very real tragedies of the refugee crisis. Manjeet talked to Charlotte Hacking about what inspired the story, the real stories beyond the pages, and why writing for young adults is so important to her.

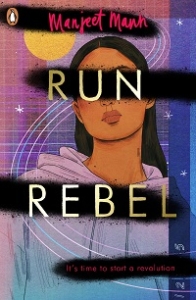

Manjeet Mann’s entry into the YA sphere has been nothing short of remarkable. Her first verse novel, Run, Rebel won the Carnegie Medal Shadowers’ Choice Award, a UKLA Book Award and the YA Sheffield Book Award and was shortlisted for the Branford Boase and the CLiPPA. The Crossing is only her second book, and was already receiving acclaim before winning the Costa Children’s Book Award. Mann is delighted, but surprised by the reactions. ‘I think I was ready for them both to tank, because they both came out during lockdowns. My schools’ tour got cancelled, and I wondered how anyone was going to hear about it. And now, I just have to keep asking myself if this is all real! I’m amazed at how well they were picked up, particularly by librarians and teachers and now I feel like I owe them my career.’

The idea for The Crossing actually came to her before the idea for Run, Rebel, back in 2014 or 15, when Mann had just moved with her partner – poet and author Joseph Coelho – to Folkstone. ‘I was interested in the themes first of all. The refugee crisis was literally on our doorstep, and there was also a real anti-refugee feeling in our town, but also anti-gentrification, there was just generally a lot of anger; you just felt it. I remember reading an article about the bodies of three men washing up on three different shores, Amsterdam, Calais and here in Dungeness. It was three men who had tried to swim the channel. And then at the same time there’s this Festival of the Sea happening in our town, with lots of talks by channel swimmers, swimming the channel for sport. There had also been a far-right demonstration in Dover, Nigel Farage wanted to stand for election in our town and we were protesting that he shouldn’t stand. Putting all of these things together I thought, there’s something here.’

At this point, Manjeet wasn’t actually writing, but acting, so her first thoughts were to make the idea into the basis for a play and she received funding from the Arts Council to do some research and development work to explore and expand on her ideas. She collected articles, read books, talked to various people, but the concept wasn’t quite coming together for her, so she put it to one side. At the same time, the book deal for Run, Rebel came along, and she concentrated her efforts into writing that. While writing, the idea occurred to her that perhaps all the research and work she’d done could be the perfect pitch for her next book. ‘I thought the best that I might do is write a play, because as an actor, that was the closest thing to me. And then when Run, Rebel was out and I pitched the idea, my editor was keen for it to be in verse, and I thought it probably could work like that, so that’s when it became a book.’

The story is told through the dual voices of Natalie (Nat), a schoolgirl from Dover, who follows in her late mother’s footsteps to swim the channel in support for refugees and Sammy, a refugee who makes the harrowing and life-threatening journey to the UK from Eritrea to escape persecution. ‘The book came to me very strongly through those two characters. And I knew the journey straight away, the beginning the middle and the end. It just landed with me one day, a little bit like divine intervention.’ The voices and stories of the two characters are cleverly linked, with the last word of one character’s voice in each verse being the first of the next character. ‘I wanted this metaphor of them being connected and being linked, even before they realise that they are. And I hadn’t seen it done before. When there have been two voices it’s been very separate and I just wanted it to flow, I wanted it to feel like a real continuous narrative.’

A lot of research went into pulling the story together. Covering so many complex themes and issues, and events that were so real for  many people in the world, carried a weight of responsibility to make the characters and events authentic and to ensure that the book truthfully represented those affected. Sammy’s story is pieced together from the very real stories of child and adult refugees, who have made the same journey for the same reasons. Over the course of three or four years she worked diligently to research and collect the stories that helped her to shape the narrative. ‘I always try to do tons of research, that’s why it always takes me such a long time to get an initial idea on to the page. It’s always quite a few years, because that’s what I feel I need. The first couple of years, when I didn’t really know what it was, it was literally reading article after article, then I made some friends in Folkstone. A lot of them worked with refugee charities and I started to get first-hand experience from them. The lady who became my sensitivity reader was on it from the very beginning, she herself is a refugee from Eritrea. She did her research and put me in touch with people who were willing to talk to me, because you don’t want to re-traumatise people.’ At the end of the process, these were the people she went back to again and again to make sure that her words rang true. ‘I needed to make sure that everything was right and everyone was happy. Especially with my sensitivity reader, I kept going back to her and asking her to tell me if anything wasn’t right. I didn’t want her to worry about my feelings, or about my art, I wanted her to tell me and tell me bluntly. She was really great at telling me when something didn’t feel right or when it wasn’t quite the right journey.’

many people in the world, carried a weight of responsibility to make the characters and events authentic and to ensure that the book truthfully represented those affected. Sammy’s story is pieced together from the very real stories of child and adult refugees, who have made the same journey for the same reasons. Over the course of three or four years she worked diligently to research and collect the stories that helped her to shape the narrative. ‘I always try to do tons of research, that’s why it always takes me such a long time to get an initial idea on to the page. It’s always quite a few years, because that’s what I feel I need. The first couple of years, when I didn’t really know what it was, it was literally reading article after article, then I made some friends in Folkstone. A lot of them worked with refugee charities and I started to get first-hand experience from them. The lady who became my sensitivity reader was on it from the very beginning, she herself is a refugee from Eritrea. She did her research and put me in touch with people who were willing to talk to me, because you don’t want to re-traumatise people.’ At the end of the process, these were the people she went back to again and again to make sure that her words rang true. ‘I needed to make sure that everything was right and everyone was happy. Especially with my sensitivity reader, I kept going back to her and asking her to tell me if anything wasn’t right. I didn’t want her to worry about my feelings, or about my art, I wanted her to tell me and tell me bluntly. She was really great at telling me when something didn’t feel right or when it wasn’t quite the right journey.’

Nat’s brother Ryan also features heavily in the storyline, as Nat watches him drawn into a far-right group, still grieving the loss of his mother and becoming increasingly disaffected by his inability to get a job, with the family about to lose their home. ‘There was a moment when I wondered whether Ryan needed a bigger part and whether he’d be a third character, but as I was working with it, it just didn’t feel right.’ She knew that his was an important story to follow though, as these were the very real experiences of people on her own doorstep. As part of the ongoing research, she sat in on workshops and took in the experiences of people in similar situations. ‘I was very aware of Ryan, and that I didn’t just want him to be this big bad wolf-like character. I wanted people to also have sympathy for him, and to be able to understand where he was coming from, because I don’t want to vilify anybody. It was one of the bits of the story that I was most scared about. Because fundamentally I don’t think people are evil, I think we’re all a product of our circumstance. I’m never excusing people for their actions, but I don’t believe people are black or white and I do try and work that into the story.’

All these issues are deeply affecting for readers of the book, and I wonder about the toll that researching and writing about such topics has on her. ‘When I was doing the interviews or reading the first-hand accounts given to support workers, I was quite affected. I remember Joe actually telling me how difficult it was to hear these stories, because I’d told him so many. As part of my process, I needed to share. He was really concerned that I should take some breaks, because I wasn’t, I was just so immersed in it. When I was reading my journal for Run, Rebel, I realised how much I was crying. I think I’d put it down to my lack of confidence in myself as a writer and a fear of embarrassing myself; that’s constantly going through my head, all the time. But actually I think it was that the subject matter was really getting to me. And I realised that through The Crossing, I was crying a lot as well. So I think it did affect me more than I realised. But I kept questioning who I was to get upset, realising what a privilege it was for me to get upset, that’s what made me carry on. But they’re hard stories, really hard stories.’

What makes her persist is the overriding feeling that these are stories which need to be told, and the impact that sharing these stories might have on their readers. ‘If it changes some minds, that’s powerful, right? Art has the ability to change minds and hearts, which is why people, especially people at the top, have always been really scared of it, so if it can change some minds, that would really be the best thing ever.’ When the book first came out, she received Arts Council funding to do some virtual visits with some schools in Kent, throughout Folkstone and Dover primarily. ‘It was sometimes quite prickly. I know it was only on Zoom, but the faces were of thunder sometimes, really not liking what I was saying. Perhaps some of it reflected what they were hearing at home and they felt I was coming into their classroom like this do-gooder artist, but I got a couple of really nice emails from teachers who said “After your Zoom, some of the kids went away and they read the books you gave them. These two lads who were pretty anti what you were saying have really come round.” That’s the best review I can get. If there are a couple of kids who thought one way and their minds have been changed, then that’s all I need.’

Charlotte Hacking is Central Learning Programmes Leader at CLPE. Prior to that she was a teacher and senior leader and taught across the primary years.

The Crossing and Run, Rebel are published by Penguin, £7.99 pbk.

David Boni

David Boni