An Interview with Alex Wheatle

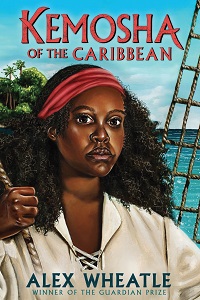

Alex Wheatle’s latest book, Kemosha of the Caribbean, is set in Jamaica in 1668, and features a bold, curious heroine who never lets injustice pass unchallenged. Born into slavery, Kemosha learns sword-fighting and wins her freedom, then takes to the seas as ship’s cook with the notorious pirate Captain Morgan – but wherever she travels, she is determined to find peaceful refuge for herself and the people she loves.

What drew you towards historical fiction, after so much success writing contemporary YA?

What drew you towards historical fiction, after so much success writing contemporary YA?

I’ve always been interested in Caribbean history, from the time that I was in prison at 18 – I read The Black Jacobeans by the great C.L.R James, and about the Haitian revolution in 1791. That really planted a seed. Years later, I was reunited with my father in Jamaica, and he took me out to see Port Royal. Most of it had been destroyed by an earthquake in 1692, but they still have a museum there which relays the story of the pirates: Calico Jack, Anne Bonny, Mary Read, and Captain Morgan. That fascinated me, and urged me to dig into it further – but it’s always been there.

In your book, the charismatic swordfighter Ravenhide mentions his West African birthplace as ‘A place where we have our own black history…tell black stories’. Is now, finally, the time to tell Black stories?

Yes, it is. It’s about time that the Black narrative was out there, in all its guises – not just about Black pain, but also Black joy. And these stories have been hidden for so long – finally they are emerging, especially from the Caribbean, the UK, and from Africa, the motherland. There’s so much to unearth about the narrative tradition of Africa and the Caribbean and of course the Atlantic Passage, and what happened prior to it…There is a lot of storytelling to be done.

What sort of research did you do to evoke the seventeenth century settings – the sugar plantation, Port Royal, Captain Morgan’s ship?

I wanted to get the basics of the history right. Jamaica in 1668 was in transition – the Spanish had been in control for 12 or so years [before the story begins]. So obviously the slaves might know some words of Spanish – many of them were captured by the Spanish – and I wanted to reference that. And I wanted to get the details about Captain Morgan’s ship, the Satisfaction, correct, as well – I had to do research on what type of ship it was, where the cabins were, where Kemosha was likely to work, being a cook. All those little fine details are very important, because I’m sure there are historians out there who might point out ‘Oh, Alex, you got this wrong!’ So those were the parameters. I wanted to get the basic things right, and then I could build my story amid them.

The language you use in the book is – as usual! – complex: the Spanish words you mentioned, the patois Kemosha and her family speak, your own invented epithets and a unique, poetic first-person narrative register. How did you make those choices?

I guess I just tried to make a balance – an educated guess at what they might have sounded like. Obviously, I can’t be transported back to seventeenth century Jamaica; so just an educated, calculated guess, with a bit of flourish from my own self to brighten it up when I deemed necessary. I had fun with that, because I love the way language is used in narrative fiction. Language is always evolving, and I feel that, especially when writing historically, language is a way of defining your characters. It sticks in the mind that bit longer. And I cannot have my characters, for example, speaking in modern-day Queen’s English; that would seem absurd. I have to marry the language with the time, the location: the Jamaica at that point of history.

You walk a very careful line between acknowledging the historical realities of violence against Black women and not putting too much overt trauma on the page. How challenging was it to find that balance?

Obviously I want to empower Kemosha, so I don’t want to concentrate too much on her being a victim, I want to empower her to have agency in her outcome, rather than wallowing in self-pity and ‘woe is me.’ Sometimes, when I read a narrative like that, I think ‘Oh no, not again – what’s this person going to do about this?’ It was important to me to put that in Kemosha’s character; that even though she’s been through so much, she still gets up and thinks about ‘OK, what can I do to change my situation?’

Kemosha functions as everybody’s conscience, too, doesn’t she – shaming the people who need shaming?

Hopefully Kemosha provides the conscience that I feel a narrative like this deserves. For me, it was one of the most important parts of the book when she lands on the Spanish Main, and discovers the village where all the people have been slaughtered. Sometimes we glamourise pirates, and Captain Morgan and the privateers, and we have a laugh about it; we see Johnny Depp playing the fool [in Pirates of the Caribbean]; but the reality was that sometimes it was very cruel, and innocent people were slaughtered. It’s so easy to forget those who have been killed over the centuries, and their lives dismissed as not important – like those people living on the Spanish Main; did they deserve what happened to them? Of course they didn’t. There’s a big debate that Kemosha has with [her friend] Tenoka: ‘Why does one nation want to batter another? Why do they want more than the other? Why can’t they live together? Why can’t there be some kind of equality?’ For me, you could use the same arguments today.

Tell me about the decision to make Kemosha a queer character.

I didn’t think ‘I’ve got to make Kemosha gay’; it was something that was organic. It’s not a massive part of the story – it’s just who she loves, who she falls for, who she feels comfortable with. To me, it’s perfectly natural for her to have this fantastic relationship with Isabella – why not? They’ve both suffered in the same kind of way. Would it be a big deal if I had her fall in love with a guy? Probably not. So it should not be made a big deal that she fell in love with a girl. Everyone is entitled to some kind of joy, some kind of living, to live a little – and if that means to love the one you want to love, then so be it.

Do you think you’ll return to this place and time in subsequent stories?

I’m sure I will at some point – I’ve just got to let the story brew in my head. But I’m sure she will return – to Jamaica, the Spanish Main, or another island…Kemosha will sail the high seas again, adventuring wherever that takes her.

Imogen Russell Williams is a journalist and editorial consultant specialising in children’s literature and YA.

Kemosha of the Caribbean is published by Andersen Press, 978-1839131219, £7.99 pbk.

David Boni

David Boni