I Know Neither the Sea nor the Stars

Neil Philip finds himself lost in Narnia.

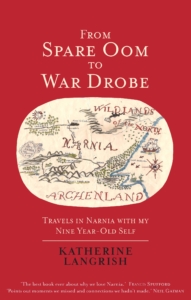

A year ago I was happily finishing an article for Books for Keeps. It was an extended review of a brilliant book by Katherine Langrish, From Spare Oom to War Drobe: Travels in Narnia with my Nine-year-old Self (Darton, Longman & Todd, £16.99, 978-1-913657-07-9).

I read that, and Laura Miller’s The Magician’s Book: A Skeptic’s Adventures in Narnia, and surrounded myself with other memoirs of childhood reading, by Alison Waller, Patricia Craig, Lucy Mangan, Francis Spufford. I re-read the first six Narnia chronicles, making copious notes on each. Everything was set fair.

I read that, and Laura Miller’s The Magician’s Book: A Skeptic’s Adventures in Narnia, and surrounded myself with other memoirs of childhood reading, by Alison Waller, Patricia Craig, Lucy Mangan, Francis Spufford. I re-read the first six Narnia chronicles, making copious notes on each. Everything was set fair.

And then, I found myself unable to open the seventh book, The Last Battle. The very thought of it made me feel shivery and sick.

How could the idea of re-reading a children’s book – a book I have read many times – trigger a kind of nervous collapse? The answer to that is complex, and it has to do with the circumstances in which I first read it, and my first response to it.

When I was nine to ten, I spent basically a whole year off primary school, struck down by a debilitating illness. I did go back into school to take the eleven-plus, but had to do so on my own, in a broom cupboard. In those days (I was born in 1955, the year before The Last Battle was published), if you were off school you were off school. There was no thought of sending work to do at home. So essentially I had a whole year living in my own imagination, and reading books that often seemed to be about boys recovering from mysterious illnesses and having transformative adventures, such as Meriol Trevor’s Arthurian time-slip novel Merlin’s Ring.

One of my refuges was the magical world of Narnia, created by C. S. Lewis, world in which, Lewis wrote, ‘images always come first.’ The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe was the first one I read, and the thought that just over there, so near you could almost touch it, was another world, transfixed me. In The Voyage of the Dawn Treader you could travel to ‘the Beginning of the End of the World’, and just keep going. And in The Magician’s Nephew, the mysterious Wood Between the Worlds contained portals to an infinite number of otherworlds.

These books were my first introduction to a genre of alternative-world fantasy to which I have remained attached all my life, and between them I owe C. S. Lewis and his friend J. R. R. Tolkien a huge debt of gratitude. Until later I came to the work of Alan Garner and Ursula le Guin, thus sparking my adult interest in children’s literature, Lewis and Tolkien seemed the undisputed masters of the genre.

There were elements in Lewis that I didn’t much like even as a child, such as the odd eruptions of snobbery and the occasional preachiness when he slips into ‘I’ mode to address the reader directly, but they were more than made up for by the sparkle of the language and the sense of rapt enchantment the texts offered.

Except, that is, for The Last Battle. It is a book that upset me profoundly. It is Lewis’s own anti-Narnia book, a book about sickness – a sickness of the mind, a sickness of the soul. As with Tolkien’s ‘The Scouring of the Shire’, the first intimation that anything is wrong is the felling of trees. I saw it as kind of despoiling of Narnia, a denial of magic itself. And last year I simply wasn’t ready to confront that childhood sense of bewilderment and anxiety, of betrayal, which I see has been lurking in my subconscious all these years, challenging me to come to terms with it.

Of course what worries adult readers most in The Last Battle is what has become known as the problem of Susan. How could Lewis dismiss  one of his central characters in such a cavalier fashion, merely because she was growing up? ‘She’s interested in nothing nowadays except nylons and lipstick and invitations. She always was a jolly sight too keen on being grown-up.’ But although that did bother me, it wasn’t the root of my dislike of the book, which was a sense of having been tricked and taken for a fool by an author I had inherently trusted.

one of his central characters in such a cavalier fashion, merely because she was growing up? ‘She’s interested in nothing nowadays except nylons and lipstick and invitations. She always was a jolly sight too keen on being grown-up.’ But although that did bother me, it wasn’t the root of my dislike of the book, which was a sense of having been tricked and taken for a fool by an author I had inherently trusted.

The problem of Susan implies an inherent misogyny, which becomes obvious and offensive in Lewis short stories such as ‘Ministering Angels’ and ‘The Shoddy Lands’. But as Katherine Langrish ably shows, in the Chronicles of Narnia, Lewis drew his female characters with deft sympathy, and gave them active roles unusual for the children’s novels of the 1950s. It all makes the problem of Susan even more problematic.

‘The Problem of Susan’ is the title of a piercing short story by Neil Gaiman, in which he examines the loneliness and loss that beset Susan when she was abandoned in our world and her siblings were all killed in a train crash and whisked off to the true Narnia. Laura Miller quotes Gaiman, ‘I would read other books, of course, but in my heart I knew that I read them only because there wasn’t an infinite number of Narnia books.’ This desire to add to the Narnia chronicles existed as soon as the books existed: Roger Lancelyn Green (whose unpublished The Land That Time Forgot influenced Lewis) features both the ‘Queen of Narnia’ and a Narnia railway station in his 1958 novel The Land of the Lord High Tiger.

An infinite number of Narnia books. Plenty of children must have wished for that. At nine, Katherine Langrish adored them so much she wrote her own book of Narnia stories, as to get more ‘the only thing to do was to try and write some of my own.’ She is very good at singling out the crucial moments in each book, those transcendent passages the give the reader that ‘stab of joy’ that Lewis aimed for. The moment when Lucy first steps into Narnia in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. Prince Rilian’s agonising return to sanity in the silver chair. Susan’s discovery of the golden chess piece in the ruins of Cair Paravel, just as in Norse myth the children of the gods find the golden chessmen of the Aesir in the grass where Asgard once stood.

From Spare Oom to War Drobe is a kind of love letter to Narnia, which both celebrates the books and forensically examines them. Langrish is able to tease out all kinds of obscure sources and references that underpin Lewis’s creation, from Milton to Plato and Bunyan and well beyond. The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, for instance, echoes the Irish immrama, voyage tales.

In her detailed discussion of The Last Battle, Katherine Langrish points out its deep affinities with an obscure satire by Edmund Spenser, Mother Hubberd’s Tale, in which ‘the Ape steals the lionskin, dresses in it and masquerades as King, despoiling the land.’ The fact that in The Last Battle it is Puzzle the donkey, rather than Shift the Ape, who wears the lionskin is in turn traced back to Aesop’s fable, ‘The Ass in the Lionskin’. This kind of archaeological excavation of layers of meaning and allusion is done so expertly you are swept along as if reading a new Narnia story.

Langrish is fascinated by the repeated ‘imagery of labyrinthine houses, passages, secret rooms and doorways into Elsewhere’ in the Narnia series, and connects this with Lewis’s childhood home. Making these kinds of connections is her essential tool of undertanding Lewis and his texts.

From Spare Oom to War Drobe is one of the most insightful and beautifully crafted books ever written about a children’s author or about childhood reading, even if it does not convince me to like The Last Battle any more than I did sixty years ago. Langrish acutely balances her vivid memories of her own first readings against her adult perspective. She sums up what the stories gave her as their lasting legacy: ‘the colour, richness and beauty, the breadth, depth and glory of the world.’

The special gift of the books, for children, is the way they transport you from the humdrum world you know, into uncharted waters under strange skies. You can sail, like Perceval in the Grail romance Perlesvaus, ‘so far that I know neither the sea nor the stars.’

Neil Philip is a writer, folklorist and poet and a longtime contributor to Books for Keeps. His collection of English folktales, The Watkins Book of English Folktales is published by Watkins Publishing, 978-1786787095, £14.99 hbk.

From Spare Oom to Ward Drobe by Katherine Langrish is published by Darton, Longman and Todd Ltd, 978-1913657079, £16.99 hbk.