Illustrating Pippi

By Holly Fulbrook, Head of Design, Oxford University Press, and illustrator Mini Grey.

When I heard about the anniversary of Pippi a couple of years ago I knew there would be exciting opportunities ahead in the OUP design studio. Pippi had long been a favourite of mine and like Mini, I was introduced to her by Lauren Child ‘s sumptuous gift edition. I was also a fan of the well-known and hugely popular Tony Ross illustrated versions too, so I knew it was going to be hard to find somebody to equal the humour and energy he bought to the series.

We spent a lot of time in the studio debating. We wanted somebody feisty, somebody who understood what Astrid Lindgren stood for and had built into Pippi’s character, somebody that would bring something fresh and perhaps unexpected to a familiar character. After much exhaustive discussion I happened to be reading Mini’s picture book The Last Wolf and had a eureka moment. I hadn’t seen much of Mini’s black and white work, was mostly familiar with her beautiful picture books but there was something in that Little Red character that made me think she’d be the perfect fit.

Once we met up to discuss, that was it! She arrived at the Oxford office clutching an original version with Ingrid Vang Nyman’s illustrations and a host of sketches before we’d even discussed what was involved. We couldn’t have made a better choice – we practically had to stop her from drawing Mr Nilsson for every chapter head (which she did regardless, and for which I couldn’t be happier).

Once we met up to discuss, that was it! She arrived at the Oxford office clutching an original version with Ingrid Vang Nyman’s illustrations and a host of sketches before we’d even discussed what was involved. We couldn’t have made a better choice – we practically had to stop her from drawing Mr Nilsson for every chapter head (which she did regardless, and for which I couldn’t be happier).

Mini Grey, illustrator

When I was a child I didn’t meet Pippi Longstocking. She just didn’t cross my path, which was generally wandering in the direction of the Moomins. My first Pippi encounter was acquiring a copy of the beautifully illustrated Lauren Child edition, in around 2009 I think.

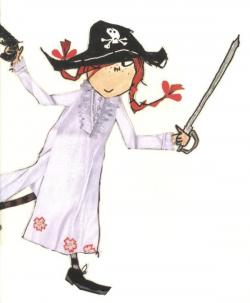

Here she is in bonkers style and wearing her father’s old nightshirt, waving sword and pistol, vowing to become a pirate.

Here she is in bonkers style and wearing her father’s old nightshirt, waving sword and pistol, vowing to become a pirate.

Later I read it to my young son Herbie, but we weren’t entirely sure about it – a bit too much horse-lifting for us. Pippi seemed impossibly strong, in a world that was otherwise fairly realistic.

But then last year I was invited by Oxford University Press to illustrate new versions of Astrid Lindgren’s books for the 2020 75th anniversary editions. My friend Niki who lives down the road is Swedish, and when I mentioned the Astrid Lindgren commission she immediately brought over her entire Astrid  Collection (and it is quite a huge collection) to properly show me just how important an institution Astrid Lindgren is in Sweden, and what an honour illustrating Pippi was. (Incidentally, Niki also makes very fine cinnamon buns and gingerbread, so I love it when these pop up in the Pippi books.)

Collection (and it is quite a huge collection) to properly show me just how important an institution Astrid Lindgren is in Sweden, and what an honour illustrating Pippi was. (Incidentally, Niki also makes very fine cinnamon buns and gingerbread, so I love it when these pop up in the Pippi books.)

In the original editions, Pippi is intrinsically linked with the illustrations of Ingrid Vang Nyman. Here’s Niki’s own copy of Pippi Goes Aboard.

To the modern (and un-Swedish) eye, Pippi looks pretty strange. I saw weird slightly alien eyes, anti-gravity hair, anatomically puzzling legs, possibly suspenders. And was she all of nine years old?

Here’s Pippi grinning at her garden gate, and rolling out gingerbread with Mr Nilsson, her monkey.

Here’s Pippi grinning at her garden gate, and rolling out gingerbread with Mr Nilsson, her monkey.

In Sweden, these images are an inseparable part of Pippi Longstocking. I started to see how strange and gutsy they were, and appreciate the pared-back lines, and limited colours that have become so emblematic of Pippi now that she has her own set of pantones.

There could be a Japanese influence to Vang Nyman’s pictures, with their lack of shadows, flat colour, and unusual diagrammatic perspectives. She made everything really clear, and worked out all the details.

Pippi Longstocking came out in 1945 and was the first work of acclaim for both author and illustrator. Is it important that the irrepressible character of Pippi emerges from five years of wartime lockdown, like a spring bursting out of a box?

So I thought I’d better properly meet Pippi.

Meet Pippi Longstocking

When we first meet Pippi, her appearance is very definitely described:

Pippi is also tremendously strong, the strongest girl in the world.

I still had problems with the impossibility and with the horse-lifting; and the excessiveness; smashing things up, being a bit too violent to a bull and breaking its horns off. There was also a view of the world that was of its time, especially the  South Sea islanders.

South Sea islanders.

More Meetings with Pippi

OK, she’s the strongest girl in the world, and is indestructible with the constitution of an ox (she eats poisonous mushrooms and she drinks random mixtures of medicines).

But as I met Pippi properly I found out how much about her I’d missed in that first brief reading aloud. I made discoveries: Pippi’s kindness and her fairness. Pippi knows what’s going on, even though it seems she doesn’t. You can be safe with Pippi. When Astrid Lindgren’s characters get really upset there’s usually a big unfairness going on.

There’s also Nature, lovingly described, especially Pippi’s wild garden, and also food, which Pippi enthusiastically creates.

To Pippi, everything’s an opportunity.

Pippi is funny.

‘Who tells you when it’s time to go to bed?’ Tommy asks. ‘I do that myself,’ said Pippi. ‘First I tell myself once, very nicely, and if I don’t obey I tell myself again, quite crossly, and if I still don’t obey, well, then there’s trouble, I can tell you.’

Pippi has a way of turning the world upside down, upending convention, and using words however she likes. She is a master of the bizarre and surreal monologue. She is a Teller of Tall Tales. She is wild and unpredictable, with the destructive potential of an unexploded bomb.

She is able to take care of herself and other people: to cook, to clean, to camp, to feed everybody, and to organise. Pippi is generous in every way. She has independent means of finance – an endless bag of gold coins. Pippi is not scared of ANYONE, no matter how important they think they are. Pippi gently perplexes those who are trying to educate her or make her do things like ‘multikipperation,’ by possibly deliberately misunderstanding things. Pippi is an uncontainable force: when she tries going to school, Pippi’s drawing of a horse refuses to be restricted to a piece of paper and is happening on the floor: she explains: ‘I’m in the middle of doing the front legs now, but when I get to the tail most likely I’ll have to go out into the corridor.’

She is able to take care of herself and other people: to cook, to clean, to camp, to feed everybody, and to organise. Pippi is generous in every way. She has independent means of finance – an endless bag of gold coins. Pippi is not scared of ANYONE, no matter how important they think they are. Pippi gently perplexes those who are trying to educate her or make her do things like ‘multikipperation,’ by possibly deliberately misunderstanding things. Pippi is an uncontainable force: when she tries going to school, Pippi’s drawing of a horse refuses to be restricted to a piece of paper and is happening on the floor: she explains: ‘I’m in the middle of doing the front legs now, but when I get to the tail most likely I’ll have to go out into the corridor.’

There’s joy in language: looking through a telescope Pippi says: ‘I can practically see the fleas in South America with this.’

There’s joy in language: looking through a telescope Pippi says: ‘I can practically see the fleas in South America with this.’

Under it all there is understated heart from Astrid Lindgren. In Pippi Goes Aboard the threat of Pippi going away looms. Here’s when Pippi is just about to leave and board her father’s ship:

She turned to Tommy and Annika and looked at them.

She turned to Tommy and Annika and looked at them.

What a strange look, thought Tommy. It was exactly the same look Tommy’s mum had on her face once when he was very, very ill.

And what is that look?

Astrid Lindgren leaves you to work that one out for yourself.

And lastly, here’s my favourite character, Mr Nilsson. I did love drawing all those Mr Nilssons.

And lastly, here’s my favourite character, Mr Nilsson. I did love drawing all those Mr Nilssons.

OUP’s new editions of Astrid Lindgren’s Pippi Longstocking books with Mini Grey’s illustrations are available now, £5.99 pbk.