Picture This: Interior with Woman

In the second of a new Books for Keeps series putting picture book illustration in the spotlight, Nicolette Jones discusses three interior scenes.

Pam Smy has emerged from my #NewIllustrationoftheDay Tweets as the Illustrators’ Illustrator. She teaches on the celebrated illustration MA course at Cambridge School of Art, and the image I posted, from Neil Gaiman’s picturebook/poem, What You Need to be Warm, received more Likes than any other by quite a margin.

Gaiman’s text was a composite of responses he received on social media when he asked for memories of being warm, and it is published by Bloomsbury, with 13 illustrators, each embellishing a spread, in aid of the UN Refugee Agency, UNHCR, to whom Gaiman gave the poem.

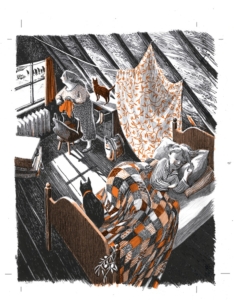

Smy’s image accompanied this section:

The tink tink tink of

iron radiators

waking in an old house.

To surface from dreams in a bed,

burrowed beneath blankets

and comforters,

the change of state from cold to warm

is all that matters, and you think

just one more minute

snuggled here

before you face the chill.

Just one.

The colours – orange and black – were a given for all the illustrations in the book, combining warmth and cold. Smy’s image is open to

What You Need to be Warm is written by Neil Gaiman. This illustration by Pam Smy. Reproduced by permission of Bloomsbury Children’s Books.

several interpretations. The text suggests a childhood memory of staying in a family house in pre-duvet days, with old-fashioned comforters, blankets and iron radiators. My own speculation to begin with was that this might be a child in a grandmother’s spare room, or part of it, where his belongings are being unpacked while he stays for the winter holiday. But the boy and his mother could be refugees who have been housed in someone’s attic with a makeshift curtain? Or is a mother/grandmother packing possessions (a comfort blanket?) for a child who is about to emerge from the cosiness of bed to the chill of having to leave home, as others, seen from the window in the snowy landscape, are already doing. Is the expression of concern on the woman’s face one of compassion for others, or anxiety about having to share their journey?

A vignette on the other half of the spread, below the text, shows the adult and child at the door, hailing the people who have passed by. To wish them well? To say goodbye? To join them? The cleverness of this image is that it merges the two possibilities: of the childhood memory of warmth in a safe home, and the experience of those who have to leave.

There is so much more storytelling in the picture. The patchwork comforter is evocative. A handmade, old-school object. Which implies another kind of warmth: the patient, loving creation of a gift to keep a child snug. It is also made of scraps of fabric that reflect the maker’s own history. Patchwork itself has an element of narrative.

The pets suggest cosiness. Two cats? Or possibly the animal on the bed is a dog (are the ears a slightly different shape?). Ambiguity like this in illustration opens up the possibility of a conversation when reading to a child. Where does the child think this is? Who is in the picture? What are the animals? It allows room for the options that mean the most to each observer. And meanwhile the essence of the text – that last moment of warmth before you get out of bed on a cold morning – is communicated whatever the particular circumstances.

Then I checked with Pam Smy about which of the interpretations above was intended. She said:

‘All of these! The image was made as the war in Ukraine was breaking out, and there were so many people being displaced. I wanted to show a mother packing up somewhere that was already makeshift, a hurried home that was made with strung curtains and belongings that were never fully unpacked, already preparing to move on as her child slept those last few delicious moments of snuggled warmth. I wanted to show the mother being aware of what was happening outside, and the child unaware.’

Smy also told me about the technique by which the image was made.

‘In this particular illustration I drew the black layer directly onto a type of plastic with a textured surface called True Grain. This holds a waxy black crayon like a Chinagraph and a dip pen and ink and a wash in a way that can replicate the feel of lithograph printing, so I was able to make a tonal textured layer on it. I painted the orange layer separately and scanned them together in Photoshop to make the two layers Bloomsbury needed for the book.’

Pam Smy’s website says she has a passion for observational drawing and sketchbooks. This image is a fine example of how traditional skills can be used with new technology without losing the precious evidence of the human hand.

It is also clear, in the line and the perspective, that Ravilious is an influence. Smy tells me more: ‘I love Ravilious, and Ardizzone and Piper – lots of those mid-century illustrators. I find the compositions of William Stobbs breathtaking.’ Smy belongs to a noble tradition.

My Baba’s Garden is written by Jordan Scott. Illustration by Sydney Smith. Reproduced with permission of Walker Books.

I wanted to choose for this piece three images whose subjects have something in common, in order to explore how differently a scene can be depicted by different artists, and therefore how many possibilities can be added to the text by an illustration. Canadian illustrator and 2024 Hans Christian Andersen Award winner Sydney Smith’s image is also a childhood memory, involving a grandmother and another room with light coming through the window, this time a kitchen: from My Baba’s Garden by Jordan Scott (Walker Books).

As in Smy’s picture, there seems to be a narrative underlying this one, even though it focuses so much on the moment – on the effect of the light, and the haze of the steam. The text encounters Grandma (‘Baba’) ‘hidden in the steam/ of boiling potatoes,/ dancing between the/ sink, fridge and stove’. We learn elsewhere that Baba picks up dropped food and grows vegetables in her garden because she had nothing to eat for a long, long time. The brightness, like Smy’s cosiness, is part of painful history. This kitchen is the happy place of a person who once starved. In the story, as in the image, there is shadow as well as light.

Smith has said he likes to create one big image on a spread when there is a big feeling it conveys or something for the reader to meditate on. This scene, with neutral colours splashed with red, loose brushstrokes, light glancing off the jars of home-made jellies, white haloes, assorted decorative kitchenware, the red heat under the pan, and detail that is sumptuous to look at without suggesting grandeur, all express the warmth of the child’s relationship with his Polish granny. There’s an empty stool in the picture that looks like an invitation to come and sit and watch Baba cook.

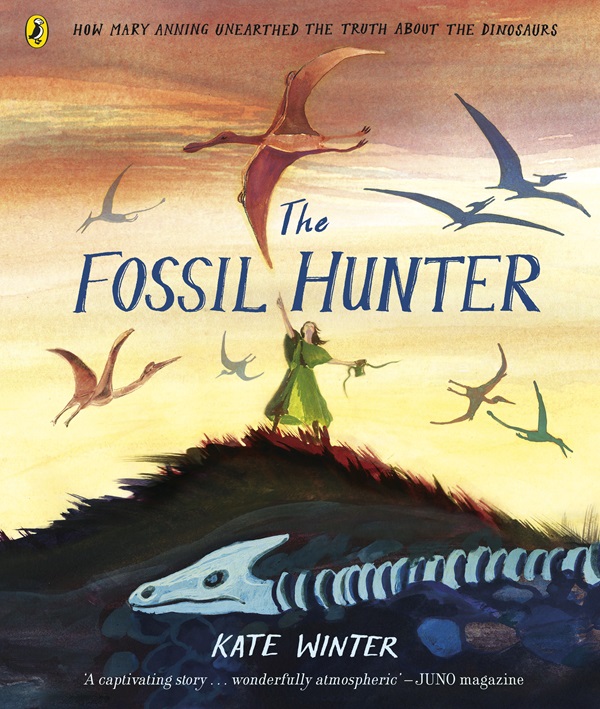

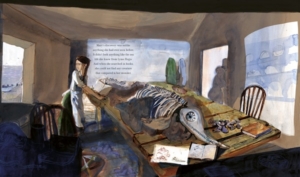

There’s an empty chair too in another inviting scene of a room with a window: in Kate Winter’s Klaus Flugge Prize-shortlisted The Fossil Hunter: How Mary Anning Unearthed the Truth About Dinosaurs (Puffin). Winter has said she originally depicted Mary’s brother sitting at the table, but removed him digitally. (Mary after all deserves the focus.) Again, technology is a tool in work that looks very much hand-made, with Winter’s loose use of ink and watercolour. The quality of light, as in Smith’s work, is very specific. Smith’s felt like sunshine coming into the room. Winter’s has the cool of seaside light, shining on her face, as we see boats on the shore through the window. Light also comes in from the other side, where passers-by look in on Mary. The sharpest detail is of Mary, of her dinosaur skeleton, and her sketchbooks. These are the most important elements of the story: the girl, and her discovery, and her recording of it.

There’s an empty chair too in another inviting scene of a room with a window: in Kate Winter’s Klaus Flugge Prize-shortlisted The Fossil Hunter: How Mary Anning Unearthed the Truth About Dinosaurs (Puffin). Winter has said she originally depicted Mary’s brother sitting at the table, but removed him digitally. (Mary after all deserves the focus.) Again, technology is a tool in work that looks very much hand-made, with Winter’s loose use of ink and watercolour. The quality of light, as in Smith’s work, is very specific. Smith’s felt like sunshine coming into the room. Winter’s has the cool of seaside light, shining on her face, as we see boats on the shore through the window. Light also comes in from the other side, where passers-by look in on Mary. The sharpest detail is of Mary, of her dinosaur skeleton, and her sketchbooks. These are the most important elements of the story: the girl, and her discovery, and her recording of it.

These three images, I hope, underline the impact of technique and imagination in illustration. The basic content is a small part. Each of these pictures involves a woman in a room with a window. But the stories they tell, and the places they take us, are so much more than that.

Nicolette Jones writes about children’s books for the Sunday Times, and is the author of The Illustrators: Raymond Briggs (Thames & Hudson); The American Art Tapes: Voices of Twentieth Century Art (Tate Publishing) and Writes of Passage: Words to Read Before You Turn 13 (Nosy Crow).

Books mentioned:

What You Need to be Warm, Neil Gaiman, various illustrators, Bloomsbury, 978-1526660619, £12.99 hbk

My Baba’s Garden, Jordan Scott, illus Sydney Smith, Walker Books, 978-1529515565, £7.99 pbk

The Fossil Hunter: How Mary Anning Unearthed the Truth About Dinosaurs, Kate Winter, Puffin, 978-0241469897, £8.99 pbk