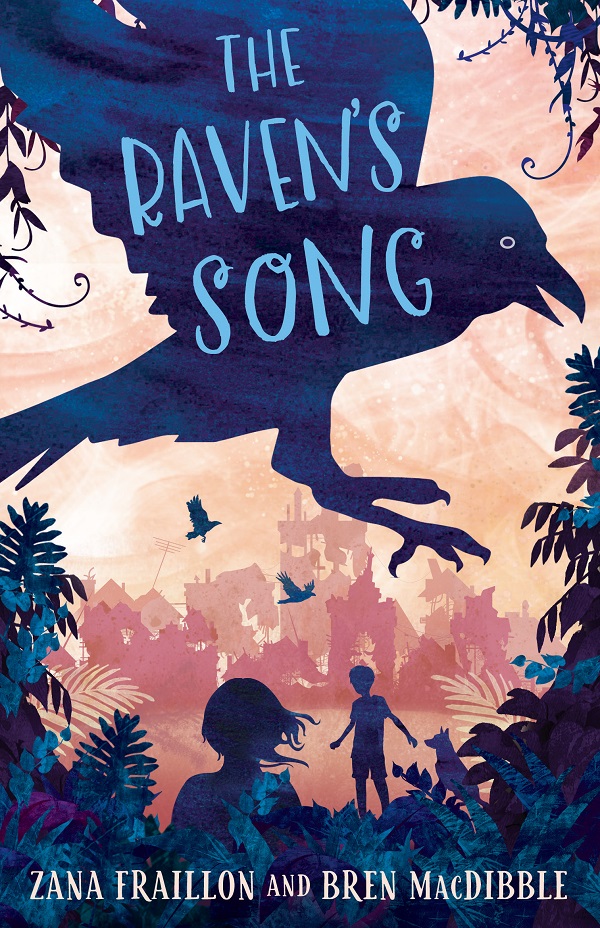

The Raven’s Song: an interview with Zana Fraillon and Bren MacDibble

Australian authors Zana Fraillon’s and Bren MacDibble’s dual-voice narrative The Raven’s Song alternates between the stories of Phoenix, who lives in a near-future world impacted by climate change and a devastating pandemic, and Shelby, who lives one hundred years in the future in a post-pandemic, post-pollution, post-city world. When their paths cross, they must work together to locate a cure for an infection endangering children and secure a path to a better future. Alison Brumwell interviewed Zana and Bren for Books for Keeps on UK paperback publication.

Did you always intend writing a novel that addressed environmental issues?

BM: I’ve been addressing environmental concerns all along and I know Zana is very knowledgeable about those, and also about history. The book was always going to have that environmental theme, then fitting that in with the history of the world which was what Zana brought to the project. I found it really expanded on my previous novels, having her tackle the historical element and then working in an environmental disaster.

BM: I’ve been addressing environmental concerns all along and I know Zana is very knowledgeable about those, and also about history. The book was always going to have that environmental theme, then fitting that in with the history of the world which was what Zana brought to the project. I found it really expanded on my previous novels, having her tackle the historical element and then working in an environmental disaster.

ZF: From my perspective most of my previous books have centred on human rights issues, but it’s incredibly clear that environmental issues are human rights issues. I knew Bren’s work was very environmentally focused and I was keen to work with someone who knew all the facets of the climate crisis and had thought carefully about what a future world might look like. The world building was instant and fantastic. It was well-timed for me because I’m doing my PhD which is on deep time, looking at the world through a gaze of geological time. I was grappling with academic research about climate crisis and what the future might look like, which is where all the future ancestor stuff came from. Having Bren there to show me how to do it was amazing.

How did you decide on the narrative structure of the novel and who would write each voice – Shelby, living in our future, and Phoenix, closer in time to us?

BM: We had read books by authors coming together to write different characters and a turnabout seemed to be the simplest way. Then we  always knew that our characters would meet at a certain point, so we actually went away to write them to that point. We planned together on Twitter, funnily enough, to create the story.

always knew that our characters would meet at a certain point, so we actually went away to write them to that point. We planned together on Twitter, funnily enough, to create the story.

ZF: When our characters finally met, we got back in contact and worked together, sending the full manuscript back and forth from that point.

BM: We were working in isolation, just as our characters existed in isolation, then came together. There was a bit of to-ing and fro-ing because Shelby’s not a very thoughtful character. Phoenix was having all these emotions and that made hers seem a bit unemotional and flat. It needed work to keep Phoenix moving, even though he wasn’t super active within each scene, then to try and make Shelby more human or a little bit more thoughtful.

ZF: There was a magical moment where we’d been working separately on our own characters. When we got to the point where they’d meet, I sent Bren across my chapters, and she sent me hers. The idea was that she would see if they fit together. Apart from one chapter that needed to be split, they did, as if we’d planned it to a T, which of course we hadn’t. We’d only had vague ideas about what would happen, but that was all. The fact that each chapter complemented the other harmoniously, as well as the characters complementing each other, felt quite bizarre and miraculous.

BM: We were so in sync, but we were working separately, and our characters were hitting the right points at the right time. They were equally exciting.

BM: We were so in sync, but we were working separately, and our characters were hitting the right points at the right time. They were equally exciting.

ZF: It was buzzy: the writing process is different for everyone, and different for each project. But I have moments when I’m writing a book where I get super-excited by the idea. Then, as the project goes on and I get to the nitty-gritty, that excitement decreases. But this was a constant buzz.

There is a third voice which comes through in the song of the Ravened Girl of the Bog. Phoenix dreams about her, which prefaces the novel. The links between her sacrifice and Phoenix’s own experiences are beautifully integrated. How much research was involved and how did you manage to blend mythology and the science?

ZF: One of the things we brainstormed early on was what modern-day child sacrifice might look like. And that was where we got the idea from: there was a pandemic and the only way the children can be saved is by freezing them, effectively sacrificing those particular children. But when I sat down to write Phoenix, I got the very strong voice of The Ravened Girl in my head. I tried to ignore her as it wasn’t the right time frame, or the right sacrifice, but I couldn’t get rid of her. So I sat down, and I got this voice onto the page, which became the preface. Then I saw how beautifully she would actually fit with the narrative and how she could be this timeless conduit between the two kids. So, Bren kindly agreed to her staying, which was good, because instead of spanning 100 years now, it’s thousands. A lot of research was involved, but it was the sort I’d already done. I’ve had a long fascination with bog bodies and bog sacrifice, and I’ve got several books on the subject. It’s something which I knew I wanted to write about. I did go back and fact-check and I think Bren found an article that described discovering bodies of children who weren’t sacrificed in bogs, though they were sacrificed. They were wearing skull helmets of previous children who had been sacrificed. Little details like that were included.

It’s actually where I want to head with my writing, at least for the little bit in the future. I’ve always loved magic realism, then I came across the term ‘folk realism’ when someone was describing Lucy Woods’ short stories, which I adore. That blending of folklore and the real world is what I want to explore.

You’re writing about characters who were impacted on by an untreatable plague and also the consequences of that. How do you feel that affected you?

ZF: It was very close to home. As Bren said earlier, we wondered whether the book would be publishable because who would want to read about a pandemic having lived through a real one? There was a fear that we wouldn’t be able to continue our project together, which we were loving. But once we decided to go ahead it became an escape. We could enter this world that was going through, or had been through, a pandemic, and were emerging from that. It was almost a way of daydreaming a way out of it.

BM: I often want to just write stories where bad things happen, but people survive even though everything changes. I like survivors.

ZF: Especially for kids, who don’t know what’s going to happen to their world and their lives. To show that whatever happens you will find a way to survive is very important, and so uplifting and positive.

Both Shelby and Phoenix have a lot of responsibility in their family lives. I think that’s very relatable to children today, young carers, for instance. Was that intentional?

ZF: Children and those sorts of family situations tend to be what I write. I was a teacher before I got into writing, and before that an integration aide in schools. I worked with a lot of kids who had incredibly hard home lives, but they didn’t see it. That was just their reality. Possibly, Bren’s and my childhood reflect that too. We didn’t really talk about who the characters would be at all.

BM: I’m a very independent person, which apparently comes from never being able to depend on people, but I wanted Shelby to be part of this community where everyone provides food and work. I made the school days shorter, where they finish at lunch, and they only go to school four days a week. Children are busy working the rest of the time. Shelby looks forward to running the egg farm, but she plans to get an apprenticeship because children are needed to do all sorts of jobs. I wanted to make her keen to be part of the community and live within a safe society.

ZF: Also having independent kids with responsibility, you can do a lot more with them in terms of story writing.

Do you think the writing experience would have been any different if you’d had the chance to meet in person, or if you’d known each other before?

ZF: There was a benefit to knowing each other through our books and writing. Possibly there was less pressure by being so far away. Collaborating was like having a second brain because we knew the book intimately like no one else could. At any time of day or night I could send Bren a message and when she woke up she responded, so it was very quick for me. Whereas if I knew we were going to meet in a week, I might have held back those thoughts until then and lost something essential.

BM: I’ve got a bit of a slow brain, so I like to consider my answers. Zana’s message would arrive and I didn’t have to respond immediately. I could reflect about what she meant and then decide yes, actually, that is a good idea and could work. I think it was beneficial having that break.

ZF: I love the collaboration process. The closest I’ve come to it is with my picture books. Writing with Bren makes me wonder what the publishing world would be like if we could find a way of doing this more often. I couldn’t have got close to this sort of writing without Bren. We just seem to fit.

BM: We have the same morals and Zana’s got this huge background knowledge. I’ve got some science fiction knowledge and our values and writing styles just seem to be at the same pace.

How do you both feel a year on since publication? A lot has changed in terms of world events, but The Raven’s Song is a very hopeful book.

ZF: Progress is too slow, and I don’t know what will motivate governments to step in and move. A lot of individuals are taking action which is hopeful.

BM: I think we always have to be hopeful; it’s part of the human condition. I do feel we’re moving too slowly, although we can make changes if we just commit to them. It’s important to do everything we can and encourage others.

ZF: That’s where the idea of that being a future ancestor brought me hope. I hadn’t come across that before so, when I discovered it, it filled me with a sense of purpose. Once you start to see your own individual action as that of a future ancestor to people thousands and thousands of years distant it suddenly clarifies what you do. It’s got nothing to do with blood ties, it’s thinking of what on this earth can we not bear to lose and trying to preserve those things.

Your book itself is an eloquent message but if you have one piece of advice or guidance for young readers, what would it be?

ZF: I recently read a fantastic article by Rebecca Solnit, about a gas company coining the term your climate footprint, to take the pressure off them as an oil and petrol company and to place it on the individual. Statistics indicate that in the last 20 to 30 years, the richest 10 % of the world’s population have been responsible for 50% or 52% of climate change and the poorest 50% contributed 7% of total emissions. I think it was Žižek who said that it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than it is to imagine the end of capitalism. So for me, start to imagine what the world might look like when that layer doesn’t exist anymore. We can do as much as we can individually, and we can be good future ancestors, but the real power will come then.

BM: I think individual action is still good. So a lot of people doing a lot of small things can add up to a significant thing.

Finally, I wonder if you’ve had any thoughts about writing together in the future?

ZF: Bren and I were recently texting each other as we do have plans to collaborate again. It’s on hold for a bit, and we haven’t shared this until now. My character is living in Doggerland which was between mainland Europe and the UK in the Mesolithic period, so 10,000 years ago when that area was all land. Bren’s character lives in the future UK, London probably, which is entirely underwater. That’s what we’ve got so far.

BM: We may have to travel to the UK.

Alison Brumwell is education and literacy consultant and chartered librarian.

The Raven’s Song is published by Old Barn Books, 978-1910646854, £7.99 pbk.