Comics: The Answer to The UK’s Literacy Crisis?

Peter Kessler argues that they are.

We’re used to Spider-Man saving the world from the Green Goblin and a multiverse of masked miscreants. But new research suggests that he could have the super-powers to do something even more valuable – something our government has signally failed to do: turn us into a nation of readers again.

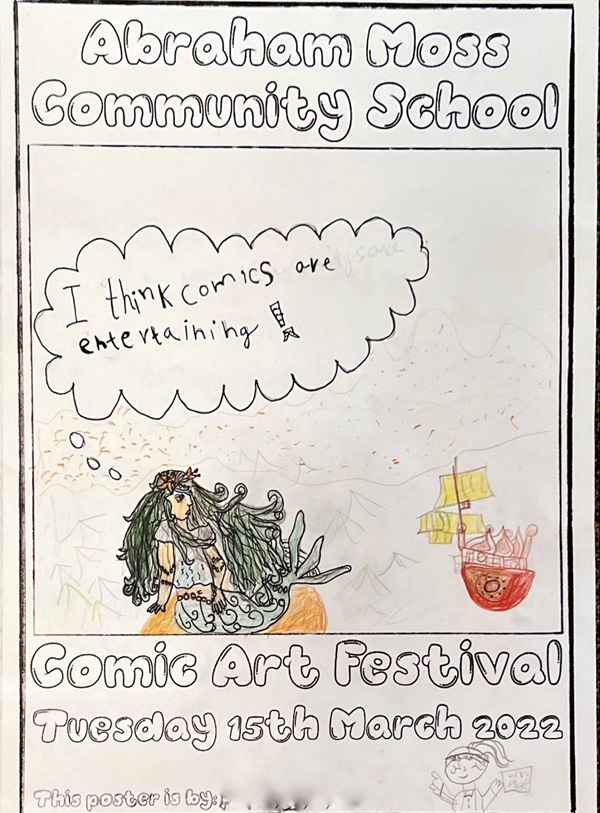

A unique project has been unfolding in a primary school in North Manchester. Abraham Moss is a typical, hard-working community school in an underprivileged area. Most of its students are from ethnic minority backgrounds, and it has a higher-than-average number in receipt of the Pupil Premium subsidy given to disadvantaged students. The school has spent two academic years participating in a Europe-wide research project entitled Comics and Literacy. The aim of the project: to analyse and quantify the impact of exposure to comics on young people.

The results are jaw-dropping.

Jaw-dropping but, for me at least, not surprising.

I used to work as an English teacher, and I saw first-hand how transformative comics can be for children disengaged from the written word. In my school the first five minutes of every English lesson were spent in silent reading. Everyone was expected to have a book. But of course there were some who never brought one along. For these defiant souls I kept a stash of graphic novels in Mr Kessler’s Cupboard. They ranged from the wordless (Shaun Tan’s The Arrival) to full Shakespeare adaptations (Ian Pollock’s King Lear). I witnessed young teenagers change from staring dumbly into the middle distance to shyly requesting the same book they had last time. I even witnessed pupils with learning difficulties increasing and improving their powers of description by adding speech-bubbles to comic-book pictures.

I used to work as an English teacher, and I saw first-hand how transformative comics can be for children disengaged from the written word. In my school the first five minutes of every English lesson were spent in silent reading. Everyone was expected to have a book. But of course there were some who never brought one along. For these defiant souls I kept a stash of graphic novels in Mr Kessler’s Cupboard. They ranged from the wordless (Shaun Tan’s The Arrival) to full Shakespeare adaptations (Ian Pollock’s King Lear). I witnessed young teenagers change from staring dumbly into the middle distance to shyly requesting the same book they had last time. I even witnessed pupils with learning difficulties increasing and improving their powers of description by adding speech-bubbles to comic-book pictures.

But this was all anecdotal, individual. The Comics and Literacy programme is different. It’s the first time a professional academic study has been conducted into the impact of comics on literacy.

Funded by Comic Art Europe, conducted by the Lakes International Comic Art Festival (LICAF), and overseen by Prof. Andrew Miles, Professor of Sociology at the University of Manchester, Comics in Literacy presents incontrovertible evidence that the combination of words and pictures produces hitherto unimaginable levels of enthusiasm, interest and dedication in young minds. In other words, comics are good for you.

During the project, 50 children in Year 3 to 4 participated in the comics programme. 50 children continued their regular syllabus, as a control and comparison group.

Here are some of the highlights from the final report:

- The average reading age of the class involved in the comics intervention rose by 18 months in the 12 months after the workshops started. The comparison group saw a rise of only 11 months.

- Two thirds of the parents of this group noted specific changes in reading habits in their children, including interest, independence and confidence in learning.

- The pupils spoke enthusiastically about receiving and reading The Phoenix comic at home, where it was often read also by participants’ siblings.

- By the end of the project, the number of students agreeing that being given a book as a gift would make them happy had risen by 13 percent while there was a decline of 14 percent among the comparison group.

- The number of children who listed reading as one of their favourite leisure activities doubled in the comics group, while it reduced in popularity among the comparison group.

These results are, self-evidently, spectacular. They suggest that comics have the power to unlock a love of reading. That in turn leads to a love of learning. And that in turn leads to better educational outcomes for our society. And when I say better education, I don’t just mean better OFSTED reports or higher percentages of grades 9 to 5 at GCSE. I mean a deep, ingrained, generational appreciation of the value of education.

So what exactly was going on in those comic-based sessions at Abraham Moss?

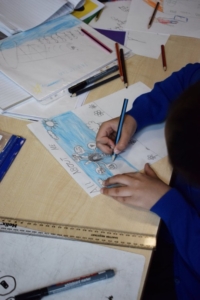

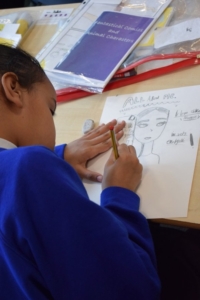

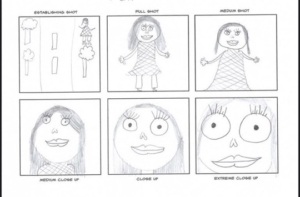

The LICAF team (Hester Harrington and Sim Leech, both experienced teachers who also work in the comics field) ran a series of ten full-day workshops with the children, focusing on both making and reading comics. The making element was a crucial part of the process, as it helped the students understand the comics format and how it can be used to tell a story.

The LICAF team (Hester Harrington and Sim Leech, both experienced teachers who also work in the comics field) ran a series of ten full-day workshops with the children, focusing on both making and reading comics. The making element was a crucial part of the process, as it helped the students understand the comics format and how it can be used to tell a story.

To help with this, they were joined by a series of professional comic artists. Marc Jackson (marcmakescomics.co.uk) ran a session called Confidence in Drawing, encouraging children to draw big, bold pictures (the only rule being that no crossing out was allowed). Sim Leech recalls the impact on a seven-year-old boy: ‘He started off saying he couldn’t draw, and he didn’t want to join in. Two hours later he was standing at the front of the class waving a huge picture he’d created, proud and happy.’

Artist Sayra Begum (sayra.co.uk) whose breakthrough graphic novel Mongrel is an unflinching account of a young Muslim woman growing up in the UK, worked with the group on autobiographical storytelling through pictures. The class’s regular Year 3 teacher commented that these workshops didn’t just improve the children’s storytelling and confidence: they also helped them understand sequencing of events and narratives. She later found that the children who had participated in the comics programme more easily grasped a lesson on first aid than those in the non-comics group.

Occasionally the impact of the programme surprised even the workshop runners themselves. Sim arrived at one session to find the children had  created a wall display about Anglo-Saxon life. With no input from the teacher, several pupils had drawn figures outside their primitive homes, with speech-bubbles talking about their lives. And as for the guided reading sessions, Sim said, ‘I’ve never known a group of seven-year-old kids sit and share books for 25 minutes without mucking about before.’ Hester Harrington recalls one boy with behavioural issues who found a particular comic which appealed to him (Strange Skies over East Berlin by Jeff Loveness and Lisandro Estherren). ‘He kept it on his desk all day, and in the end we let him keep it. It made him engage in the workshop, and he found a way to put his energy into his learning through comics.’

created a wall display about Anglo-Saxon life. With no input from the teacher, several pupils had drawn figures outside their primitive homes, with speech-bubbles talking about their lives. And as for the guided reading sessions, Sim said, ‘I’ve never known a group of seven-year-old kids sit and share books for 25 minutes without mucking about before.’ Hester Harrington recalls one boy with behavioural issues who found a particular comic which appealed to him (Strange Skies over East Berlin by Jeff Loveness and Lisandro Estherren). ‘He kept it on his desk all day, and in the end we let him keep it. It made him engage in the workshop, and he found a way to put his energy into his learning through comics.’

At the same time, all the pupils were receiving a weekly copy of The Phoenix comic, posted directly to their homes. As well as sharing the comic with their family members, this meant the reading at school could continue at home – and getting their own comic delivered personally made the children feel valued and special.

All this positivity is against a particularly gloomy background for literacy standards in British schools. Last September the National Literacy Trust published their latest report on children’s and young people’s reading. It was a depressing summary: 56% of 8- to 18-year-olds don’t enjoy reading in their free time – an all-time low statistic. And levels of reading enjoyment were found to be weakest for children from disadvantaged backgrounds. Our programme didn’t just buck that trend. It obliterated it.

All this positivity is against a particularly gloomy background for literacy standards in British schools. Last September the National Literacy Trust published their latest report on children’s and young people’s reading. It was a depressing summary: 56% of 8- to 18-year-olds don’t enjoy reading in their free time – an all-time low statistic. And levels of reading enjoyment were found to be weakest for children from disadvantaged backgrounds. Our programme didn’t just buck that trend. It obliterated it.

So, Comics in Literacy was a success. But it would mean nothing if it ended there.

Under the leadership of its director Julie Tait, LICAF is continuing its work with a new project, funded by the Paul Hamlyn Foundation. Called Comic Potential, it is expanding the workshops into several primary schools and special schools in Barrow and Kendal. On top of that, the team is working on a suite of online resources that can be rolled out across the country and used by any school, anywhere.

We have also run a similar project in a remand centre, showing how comics can promote literacy with offenders – and the results were again impressive. A parallel project, From Ink to Action, is using comics to promote awareness of climate change. And LICAF is also busy creating touring exhibitions and activities across library consortia, engaging children in manga and comics with participatory work curated by young people.

The overall slogan is Comics Can Change the World. And, despite a long history of sniffy disregard, the data is telling us that it might actually be true

Peter Kessler is a former TV producer, English teacher and the author of The Complete Guide to Asterix. He is the Chair of the Lakes International Comic Art Festival board, and he also runs the Oxford Comics Network, devoted to promoting the academic study of comics at Oxford University.