This article is in the Beyond The Secret Garden Category

Beyond the Secret Garden: Science and Science-Fiction

In the latest in their Beyond the Secret Garden series examining representations of Black and racially minoritized people in children’s literature, Darren Chetty and Karen Sands-O’Connor seek out universal access in science-fiction writing for children.

Writing in 2004, Farah Mendlesohn argued that there was a ‘paucity of fiction for children which fits the definition of science fiction as commonly accepted by adult science fiction readers’ (‘Is there any such thing as children’s science fiction?’); she went on to suggest that there was almost no children’s science fiction with characters from a racially minoritised background. Mendlesohn’s definition was too rigid to accept writers such as Andre Norton, whose Star Ka’at series appeared as early as the mid-1970s, or Virginia Hamilton (Justice and her Brothers) or K.A. Applegate (whose Animorphs series had a multiracial cast of characters), even though Karen had included all of these in her 1999 critical study, Back in the Spaceship Again (Greenwood Press), co-written with Marietta Frank. The fundamental argument for many scholars about what constitutes children’s science fiction is the purpose or aim of a text. Mendlesohn suggests it must create cognitive dissonance for the reader by changing (and often destabilizing) the rules of the universe, and that most children’s literature does not (want to) do this for a readership that is only just learning the rules and wants to believe the universe is fair and just. Other scholars, including Karen, suggest that children’s science fiction is about the ‘willingness to meet aliens, to travel and visit new galaxies, and to consider science not yet discovered and technology not yet invented’ (Back in the Spaceship Again p. 9) – activities which often require both author and reader to accept a blend of Mendlesohn’s cognitive dissonance with a belief in the possible that might appear to be as much fantasy as science fiction. Yet, however science fiction for children has been defined, the universe(s) portrayed were often dominated by white earthlings throughout most of children’s literary history. That the whiteness of the universe is connected to colonialism has been noted by many, including Ebony Elizabeth Thomas in The Dark Fantastic (2019). But alternative traditions have always existed, and science fiction with global majority characters, often imbued with myths, traditions, and references from cultures beyond Europe, are becoming more readily available.

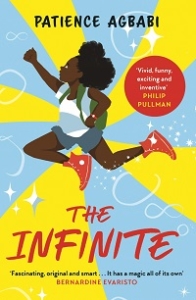

Patience Agbabi’s Leap Cycle series, beginning with The Infinite (Canongate 2020) is a good example of this. Elle, the protagonist, has a Nigerian grandmother, and Nigerian food, African hair products, and Nigerian cultural values are found throughout the novels. Because the novels are about time travel (to the past and the future), they also include historical Black figures including Francis Barber and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. Agbabi’s books are not science fiction in the sense that the mechanism for time travel is a ‘gift’ that Elle has, one that she recognizes but could not necessarily explain scientifically. However, the plot of time travel, and the emphasis on the science and mathematics of time, are attributes that encourage readers to explore the possible – including the possibility that an African British girl with autism might be an excellent scientific practitioner.

Patience Agbabi’s Leap Cycle series, beginning with The Infinite (Canongate 2020) is a good example of this. Elle, the protagonist, has a Nigerian grandmother, and Nigerian food, African hair products, and Nigerian cultural values are found throughout the novels. Because the novels are about time travel (to the past and the future), they also include historical Black figures including Francis Barber and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. Agbabi’s books are not science fiction in the sense that the mechanism for time travel is a ‘gift’ that Elle has, one that she recognizes but could not necessarily explain scientifically. However, the plot of time travel, and the emphasis on the science and mathematics of time, are attributes that encourage readers to explore the possible – including the possibility that an African British girl with autism might be an excellent scientific practitioner.

Malorie Blackman once wrote that as a kid, she ‘searched out books about alien life forms on other planets and longed to meet some. Maybe they held answers that we on earth were still striving to find’ (Just Sayin’ 26). Her science fiction books, including Robot Girl (Barrington Stoke 2015) and Hacker (Corgi 1992), depict both the dangers of technology and the benefits. In Robot Girl, Claire has to decide what to do about Maisie, her father’s AI creation using Claire’s memories; in Hacker, Vicky has to use her computer hacking skills to save her father from prison. Although Blackman uses her background in computer science to give the stories realistic detail, the plots revolve around scientific ethics. For Blackman, science is neither inherently good nor bad, but she does believe in the power of children to address and act on the moral questions that new technology raises.

This is also the theme of Chanté Timothy’s humorous graphic novel for young readers, Supa Nova (Nosy Crow 2025). Nova is a young scientist who tries to create a plastic-eating creature to benefit the environment. Unfortunately, Nova succeeds too well, and the monster grows to gigantic proportions feeding on more than just discarded plastic. Although Nova is somewhat impulsive in her scientific endeavours, her parents (who are also scientists) have taught her how to think through a problem, and with the help of her sister she is able to shrink the creature down again.

Many children’s science fiction stories do include some kind of non-human being, and Zanib Mian’s My Friend the Alien (illustrated by  Sernur Isik, Bloomsbury 2020) uses the character of the alien to encourage readers to think about the racism and bullying that comes from ‘othering’ people. The story is told from the point of view of Maxx from the planet Zerg who comes to study humans on earth. He meets Jibreel, whose classmates call him an alien because he is a refugee. Although the story deals with racism and bullying more than with space travel or technology, Mian does not leave science out altogether. Jibreel, who had won a science award in his former home country, is able to help fix Maxx’s spaceship so that (ultimately – after a rather large hiccup) Maxx can return home.

Sernur Isik, Bloomsbury 2020) uses the character of the alien to encourage readers to think about the racism and bullying that comes from ‘othering’ people. The story is told from the point of view of Maxx from the planet Zerg who comes to study humans on earth. He meets Jibreel, whose classmates call him an alien because he is a refugee. Although the story deals with racism and bullying more than with space travel or technology, Mian does not leave science out altogether. Jibreel, who had won a science award in his former home country, is able to help fix Maxx’s spaceship so that (ultimately – after a rather large hiccup) Maxx can return home.

In contrast in Kenechi Udogu’s Augmented (Faber & Faber 2025) science is central to the story, but racism has only a subtle presence. Akaego is a British Nigerian Londoner in a world where extreme weather has made plant life and food scarce. Society is stratified – people are given levels which indicate the type of work they can do – and sixteen-year-olds must have one socially useful ability surgically augmented. Akaego’s ability involves her voice which can produce a frequency that accelerates plant growth.

Augmented takes place in a familiar multicultural London. Akaego’s friend Jaden is Black and her love interest Joon, son of the mayor, has South Korean family. Akaego’s father has a North London accent and her mother switches between English and Igbo. The family eat plantain and ‘more Igbo-influenced dishes than some people who lived in Nigeria’, (p147) and Akaego has items of clothing made from adire fabric. Akaego is portrayed as confident and secure in her sense of cultural background.

As we encounter a rebel group named the Freestakers, we learn of the possibility that the powers to be are in fact restricting the amount of food available. As one character puts it, ‘If you control the food supply, you control the people’ (p72). Political questions, such as the ethics of direct action and the limits of governmental power emerge. Yet though we are told that immigration has been ended, we do not encounter anti-immigrant sentiment or a sense of heightened racism in the world of Augmented. One reading would be that Udogu doesn’t believe this to be likely in a world of diminished resources. Another is the she wishes to emphasise the agency of her young characters in difficult circumstances and offer a narrative that affirms racially minoritised youths.

Dr Darren Chetty is a writer and a lecturer at UCL with research interests in education, philosophy, racism, children’s literature and hip-hop culture. He contributed to The Good Immigrant, edited by Nikesh Shukla, and has since published five books as co-author and co-editor. He tweets at @rapclassroom.

Karen Sands-O’Connor is a Visiting Professor of Education at the University of Sheffield. Her book British Activist Authors Addressing Children of Colour (Bloomsbury 2022) won the 2024 Children’s Literature Association Honor Book Award.

Darren and Karen’s book Beyond the Secret Garden: Racially Minoritised People in British Children’s Books is out now, published by English Media Centre.

Books mentioned:

Back in the Spaceship Again, Karen Sands-O’Connor, Marietta Frank, O/P

The Leap Cycle, Patience Agbabi, Canongate, various, £7.99 pbk

Just Sayin’, Malorie Blackman, Merky Books, 978-1529118698, £10.99 pbk

Robot Girl, Malorie Blackman, Barrington Stoke, 978-1781124598, £7.99pbk

Hacker, Malorie Blackman, Corgi, 978-0195631951, £6.99pbk

Supa Nova, Chanté Timothy, Nosy Crow, 978-1805130666, £8.99 pbk

My Friend the Alien, Zanib Mian, illus Sernur Isik, Bloomsbury Readers, 978-1472973900, £6.99 pbk

Augmented, Kenechi Udogu, Faber & Faber, 978-0571385843, £8.99pbk