This article is in the Category

A Story from the Archive: The Queen’s Knickers and Other Stories

Sarah Lawrance returns to the Seven Stories archives to examine The Queen’s Knickers.

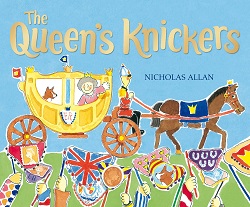

Amid the tidal wave of press coverage of the Platinum Jubilee, a curious snippet put me in mind of Nicholas Allan’s 1993 picturebook The Queen’s Knickers: apparently, the committee tasked with approving official memorabilia for the Coronation ‘unanimously agreed to reject an application for crown-embroidered knickers’. Elsewhere I read that, in 2015, a pair of Queen Victoria’s cotton knickers with a 45” waistband fetched £12,090 at auction. Clearly the public fascination with royalty and underwear has quite a history.

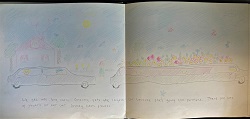

Yet this was not in fact the genesis of Nicholas Allan’s story. A dummy book in Allan’s archive at Seven Stories which pre-dates The Queen’s Knickers tells a rather more complicated tale. Granny’s Longest Holiday is a 32-page picturebook draft with text and full-sized illustrations drawn in coloured pencil. At the beginning (Tuesday) we see Granny sitting up in bed, welcoming her affectionate granddaughter with open arms; but on the next page Granny has disappeared – in her place is a pink coffin on a wooden stand, with the text ‘here she is on Friday, all packed up for her longest holiday’. The granddaughter throws herself enthusiastically into the whole process of ‘saying goodbye’: dressing up smartly (she wants to wear her flowery dress but has to compromise with flower knickers under a sober black outfit); riding in the  funeral cortège (‘Granny gets the longest car because she’s going the furthest’), singing loudly at the service (‘so Granny can hear me in her box’), and peering curiously into the grave (‘It’s funny granny’s going down when heaven is up. She must be going by tube.’) The climax is a magnificent tea back at

funeral cortège (‘Granny gets the longest car because she’s going the furthest’), singing loudly at the service (‘so Granny can hear me in her box’), and peering curiously into the grave (‘It’s funny granny’s going down when heaven is up. She must be going by tube.’) The climax is a magnificent tea back at  granny’s house – a double page spread of sausages, sandwiches, crisps and cake, as in all the best children’s stories. At bedtime, the little girl asks her mother when granny will be coming back and is told ‘Granny’s gone on her longest holiday, dear, so she won’t be back;’ yet the girl has the last laugh

granny’s house – a double page spread of sausages, sandwiches, crisps and cake, as in all the best children’s stories. At bedtime, the little girl asks her mother when granny will be coming back and is told ‘Granny’s gone on her longest holiday, dear, so she won’t be back;’ yet the girl has the last laugh  because that very night granny appears beside her bed to say thank you for seeing her off, for singing so nicely, dancing so well, and most of all for wearing her flower knickers.

because that very night granny appears beside her bed to say thank you for seeing her off, for singing so nicely, dancing so well, and most of all for wearing her flower knickers.

Clearly Allan (who has lived from birth with a serious heart condition and has spent long periods in hospital) wanted to make a point about the need for adults to talk honestly with children about death. There are some successful visual jokes – like the huge hearse which stretches across the double page spread – but overall the story doesn’t quite work as a book for children. However, it was the beginning of something: as Allan’s editor said to him at the time ‘What you really want to do is write a book about knickers…’

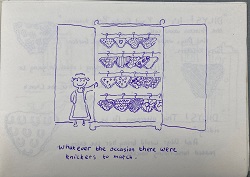

The Queen’s Knickers came next in order of composition, but at first there seemed little hope of the book ever being published, on account of the lead character being so recognisably not just any queen but HM Queen Elizabeth II. In an attempt to circumvent this issue, Allan drafted The Princess’s Knickers, with a generic fussy princess character in place of the Queen. The Princess has the largest collection of knickers in the world, kept in a huge wardrobe, under the watchful eye of her maid Dilys – motifs which will be familiar to readers of The Queen’s Knickers. Then the story takes another turn – an invitation to the Prince’s Birthday Ball throws the Princess into a fit of despair when she is quite unable to find a pair of knickers that she is happy to wear. In the end, she passes the invitation on to Dilys, who has no such qualms; Dilys has a wonderful time at the ball and ends up marrying the prince and having three children. Meanwhile the fussy princess continues to dress more elegantly than anyone else, and, when she dies, is laid out in her coffin wearing the most exquisite pair of jewel-encrusted white satin knickers ever made, though of course nobody ever sees them: a sorry end for a decidedly unsympathetic character. Not surprisingly, this version was abandoned when The Queen’s Knickers was finally – happily – published.

The Queen’s Knickers came next in order of composition, but at first there seemed little hope of the book ever being published, on account of the lead character being so recognisably not just any queen but HM Queen Elizabeth II. In an attempt to circumvent this issue, Allan drafted The Princess’s Knickers, with a generic fussy princess character in place of the Queen. The Princess has the largest collection of knickers in the world, kept in a huge wardrobe, under the watchful eye of her maid Dilys – motifs which will be familiar to readers of The Queen’s Knickers. Then the story takes another turn – an invitation to the Prince’s Birthday Ball throws the Princess into a fit of despair when she is quite unable to find a pair of knickers that she is happy to wear. In the end, she passes the invitation on to Dilys, who has no such qualms; Dilys has a wonderful time at the ball and ends up marrying the prince and having three children. Meanwhile the fussy princess continues to dress more elegantly than anyone else, and, when she dies, is laid out in her coffin wearing the most exquisite pair of jewel-encrusted white satin knickers ever made, though of course nobody ever sees them: a sorry end for a decidedly unsympathetic character. Not surprisingly, this version was abandoned when The Queen’s Knickers was finally – happily – published.

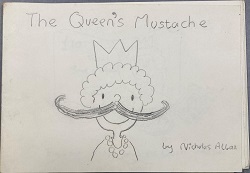

In another, later, unpublished story, The Queen’s Mustache, we meet the Queen again, but this time there are no knickers. The Queen gets  tired of always being recognised and likes to go about in disguise – as a horse, as a postman, and as a lavatory attendant (the lavatory being another signature Allan motif). She foils a horse theft, is nearly locked out of the palace, and enters a Queen Lookalike competition in which she wins only third prize; after this she decides it’s probably best just to be herself, even if she is the Queen.

tired of always being recognised and likes to go about in disguise – as a horse, as a postman, and as a lavatory attendant (the lavatory being another signature Allan motif). She foils a horse theft, is nearly locked out of the palace, and enters a Queen Lookalike competition in which she wins only third prize; after this she decides it’s probably best just to be herself, even if she is the Queen.

Nicholas Allan’s scatological humour may be more universally appreciated by children than adults, but – as his archive shows – striking the right balance between pushing the boundaries and being un-funnily crass – or downright bizarre – is a hard act to pull off. The Queen’s Knickers, first published in 1993, works because its juxtaposition of HM the Queen and Knickers feels just a little naughty, without being actually rude; its portrayal of the Queen is affectionate, relatable and joyful – and she even gets to dive out of a plane long before her famous meeting with James Bond at London 2012.

In 2020 the Society of Authors launched The Queen’s Knickers Award, generously endowed by Nicholas Allan, for an illustrated book ‘that strikes a quirky, new note and grabs the attention of a child, whether this be in the form of curiosity, amusement, horror or excitement’. The 2022 award, announced in June, was to Inch and Grub, a Story about Cavemen, written by Alastair Chisholm and illustrated by David Roberts. Nominations for the 2023 award open in August.