This article is in the Beyond The Secret Garden Category

Beyond the Secret Garden: Listen to This Story! From Archive to Exhibition

For this issue of BfK’s long-running series Beyond the Secret Garden, Darren Chetty and Karen Sands-O’Connor offer a different kind of column, about the importance of preserving and celebrating children’s books in a national institution. Listen to this story about an exhibition, the first exhibition entirely focused on the history of children’s literature by and about Black Britons.

Like many stories, this one begins before the exhibition was born, in the archive of Seven Stories, the UK’s National Centre for Children’s Books in Newcastle. In 2014, Seven Stories began a project to expand their archival holdings. The organization, which includes materials from hundreds of children’s authors, illustrators and publishers, primarily from the 1930s onwards, wanted to ‘ensure our Collection tells fully the story of British children’s literature’ (Seven Stories) including reflecting social and cultural diversity. The Collecting Cultures project at Seven Stories produced many outcomes, not least of which was bringing several authors and scholars together in a one-day symposium in November 2017. The Diverse Voices symposium, whose participants included Patrice Lawrence, Catherine Johnson, Verna Wilkins, and Alex Wheatle, allowed space for authors to talk about the difficulties of getting—and staying—published in the British children’s book world. Seven Stories’ initiatives over the next five years led to the acquisition of material from John Agard, Grace Nichols, Valerie Bloom, Verna Wilkins, Errol Lloyd, and Ken Wilson-Max.

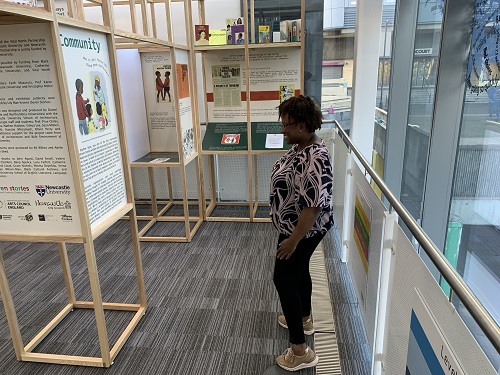

But while it is important to collect the work of these authors, preserving history is not enough if it means that their work is filed away in archives, traditionally places that are inaccessible to the general public. Ensuring that authors are in the public record is not the same as getting the public excited about their work, and it is not the same as recognising those authors’ struggles and successes. Archives provide the material for telling something about history, but someone has to decide that a story is worth telling. By working in collaboration with Newcastle University and the City Library in Newcastle, Seven Stories was able to bring Listen to This Story! An exhibition about children’s books and Black Britain to life.

The exhibition organisers (like any good storytellers) had to consider how best to balance their main subjects’ passion and persistence against the difficulties and barriers they faced. Publishing for Black British authors has often been a labour of love—with emphasis on both labour and love, as authors struggled to find recognition in a very white British publishing industry. But the audience for the exhibition (as for any good children’s story) also had to be a consideration. This was the first time that Seven Stories set a major exhibition in the centrally-located Newcastle City Library rather than the Seven Stories Visitor Centre. The change in venue has advantages—a wide range of people in terms of age and other demographics visit the library—but these advantages also mean that the exhibition had to speak to all of those people. Community was, therefore, key to this story. The exhibition looks at the importance of community to Black British authors. This includes communities of Black activists who demanded reading materials like Bernard and Phyllis Coard’s Getting to Know Ourselves (Bogle L’Ouverture 1972) for Black children being failed by the British educational system. It also includes community publishers, from the independent Black publishers such as New Beacon and Bogle L’Ouverture to community centres like Centerprise in Hackney that became publishers for the young Black people in their writing groups. Publications like Talking Blues (Centerprise 1976) allowed young Black Britons to imagine themselves as writers.

But – partly as a nod to the many communities in Newcastle who may experience the exhibition—the global and the present-day local community are also critical. The idea for the exhibition started with African-Caribbean authors, illustrators and publishers who created books for children in the 1970s. But then and now, the Black British community has been wider than this, and the exhibition celebrates the work of British African authors including Ifeoma Onyefulu and Ken Wilson-Max. Like Britain, the Black British community is not a single voice but many. Newcastle’s community is also made up of many people from all walks of life, and the exhibition has a full programme of author and storytelling events to bring different communities together with the common goal of learning about Black British history and culture. Black British literature and history is British literature and history, and all children can and should experience it.

Voice is another main theme of the exhibition, because ‘having a voice’ doesn’t just mean speaking (or writing) but being heard. British children’s literature has not always made room for Black voices, but many artists and writers kept speaking until they were heard. The exhibition celebrates the patois of the Caribbean through Valerie Bloom’s prominently displayed quotation from the poem Show Dem (Touch Mi, Tell Mi Bogle L’Ouverture 1983) and the manuscript page from John Agard’s Calypso Alphabet (Collins 1989). It also indicates the ways that Black authors use their voice to counter stereotypes of Black people, as Ifeoma Onyefulu does in her discussion and creation of A is for Africa (Frances Lincoln 1993). And it celebrates children’s voices—through publications like Talking Blues, but also through the letters children write to authors. Designed by architect Daniel Goodricke, Listen to This Story! includes an interactive space for workshops, with display space for children’s drawings and stories: their voices matter too.

These two elements, having a supportive community and being able to speak and be heard, help children build strong identities, and identity is the third theme of the exhibition. Petronella Breinburg’s and Errol Lloyd’s character Sean, in My Brother Sean (Bodley Head 1973) is a classic and important story of Sean’s first day at school. Afraid of not being accepted, he uses his voice—Lloyd depicts him with mouth wide open and in tears. The community of the classroom steps in and steps up, and makes Sean feel secure. Lloyd wanted to depict Black Britishness as ‘ordinary’ at a time when Black children often suffered both institutional and individual racism, but his books suggest that feeling ordinary, and having a sense of belonging, requires a community in which your voice matters.

The author Grace Nichols’ novel, Leslyn in London (Hodder and Stoughton 1984) is about a girl from Guyana moving to Britain, and the feeling of belonging to two places—a duality which is shown positively in the exhibition by a letter from the National Library of Jamaica accepting Nichols’ novel into the collection. The explanatory blurb notes that Nichols’ work is part of the British Library as well. Identity can be multiple and fluid, changing and adapting. And just as the community centre Centerprise valued the voices of young writers enough to publish their work and let them—literally—see themselves as writers, books like Ken Wilson-Max’s Eco Girl (Otter-Barry 2022) allow readers to see themselves as activists with agency, caring for the planet that we all share. The exhibition’s featuring of Wilson-Max’s bold artwork from Eco Girl is a celebration of Black agency—but also of children’s agency, no matter what their background. Strong communities can build identities, but strong individuals build communities as well.

Listen to This Story! tells a narrative of Black British history and children’s book publishing through community, voice and identity. But the exhibition tells other stories too. By highlighting illustrations, letters and drafts from the archival collections alongside children’s books, the culture and history of the books and their creators are valued as having national significance. This significance is not hidden away, but celebrated by turning archive documents and collections into a narrative that can change people’s thinking, add to their understanding, and above all increase their enjoyment of Black British children’s literature for all British readers.

Listen to This Story: An exhibition of children’s books and Black Britain is on display through 30 November, 2022, at Newcastle’s City Library, after which a national tour is planned.

Karen Sands-O’Connor is the British Academy Global Professor for Children’s Literature at Newcastle University. Her books include Children’s Publishing and Black Britain 1965-2015 (Palgrave Macmillan 2017).

Darren Chetty is a teacher, doctoral researcher and writer with research interests in education, philosophy, racism, children’s literature and hip-hop culture. He is a contributor to The Good Immigrant, edited by Nikesh Shukla and the author, with Jeffrey Boakye, of What Is Masculinity? Why Does It Matter? And Other Big Questions. He tweets at @rapclassroom.