This article is in the Beyond The Secret Garden Category

Beyond the Secret Garden: Witness Literature

By Darren Chetty and Karen Sands-O’Connor.

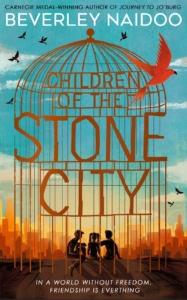

Writing for Books for Keeps (258) earlier this year, Beverley Naidoo shared how her visit to the Occupied Palestinian Territories and East Jerusalem in 2000 and 2016 informed her latest novel Children of the Stone City. Written as a work of fiction, her decision to name the city in the book ‘as simply ‘The Stone City’, with its inhabitants universalized as ‘Permitteds’ and ‘Nons’, would come later.’

Naidoo describes her approach to fiction as ‘witness literature’, a term she learnt from fellow South African Nadine Gordimer. Both writers grew up racialised as white by the Apartheid regime. Acknowledging that witnessing in fiction is matter of degree, Political Scientist Ian King suggests that ‘[a] radical literature of witness says, “Hey, look at this! Do you see what’s going on here? How are you going to react? Can you just stand by and shrug your shoulders?”’ King acknowledges that where writers are ‘witnessing’ rather merely ‘observing’ the writing ‘clearly has a (often brazenly didactic) “point” to it.’

Naidoo describes her approach to fiction as ‘witness literature’, a term she learnt from fellow South African Nadine Gordimer. Both writers grew up racialised as white by the Apartheid regime. Acknowledging that witnessing in fiction is matter of degree, Political Scientist Ian King suggests that ‘[a] radical literature of witness says, “Hey, look at this! Do you see what’s going on here? How are you going to react? Can you just stand by and shrug your shoulders?”’ King acknowledges that where writers are ‘witnessing’ rather merely ‘observing’ the writing ‘clearly has a (often brazenly didactic) “point” to it.’

This potential didacticism is one of the reasons that witness literature for children is sometimes a subject of debate. Concerns about a work of literature being propagandist should not be rejected out of hand, in our view. But we should also question any assumptions that literature and childhood can exist entirely independently of politics. A further reason for controversy is the increased attention to the identity of the author and a concern in promoting ‘own voices’ literature. Naidoo addresses this concern in a 2004 speech entitled ‘Out of Bounds: Witness Literature and the Challenge of Crossing Racial Boundaries’: ‘It is essential to be campaigning and promoting access for more black writers, illustrators, editors, publishers, designers – for more black participation in every area of production – but this political activity should not dictate creative activity. The work must stand or fall in terms of its own artistic merit. To judge work in terms of the so-called racial classification of the author is a backward step. It confirms the racialisation of experience and imagination.’

Naidoo offers a distinction – between political and creative activity – that makes demands of the witness author beyond the page, while also holding open the possibility for understanding. This is a position in keeping with the Anti-Apartheid struggle of which she was part.

In any violent incident, people can be positioned within that incident—as victims or aggressors—or they can be present but not directly involved. These outsiders have a potentially important role to play, bearing witness to the event and often speaking for or with the victim against the aggressor. When the violence is perpetrated by a nation or government against another nation or some of its own people, witnesses sometimes choose to become authors, telling the story of the atrocity so it can reach more people. Witness writing has been an important part of children’s literature for hundreds of years, and has motivated young people to take action. However, the way that the narrative is told and who it is told by has an effect on who benefits most from witness-bearing.

A prime historical example of this is the 18th and early 19th century abolitionist writing by British women authors like Amelia Opie. Opie wrote poetry, such as ‘The Black Man’s Lament: Or, how to make sugar’ (1826), to encourage white British child readers to participate in sugar boycotts and become part of the abolitionist movement. Using the power of sympathy, Opie addressed white British children in an effort to ‘move souls to pity’ the enslaved. This rhetorical technique empowered young people to take action, but also encouraged the continuance of power hierarchies which gave agency to white children rather than enslaved people. Claire Midgely points out that these boycotts had ‘no clear impact on West India sugar imports’ (‘Slave sugar boycotts and anti-slavery culture’ p. 155) and thus no direct influence on the enslaved people in the Caribbean. Opie was a ‘witness from a distance’—she never travelled to the West Indies and what she knew about enslavement came from her connections with Quakers and other religious groups that objected to the system of enslavement. This meant that Opie’s influence was felt mostly in Britain by unenfranchised British people—mostly women and children—who, despite their lack of voting ability, could have an impact on national politics through participation in sugar boycotts. Many supporters of women’s rights in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including Emmeline Pankhurst and Elizabeth Blackwell, credited childhood abolitionist literature for their activism later in life. Opie herself also increased her fame through her abolitionist poetry, and though there is nothing to suggest she did it for this reason, the fact remains that white women and children benefitted more directly from abolitionist writing for children than the enslaved people they were moved to help.

Witness literature for children does not always benefit the author who writes it. Anthony Delius, a white South African journalist, spent his entire career writing against the Nationalist party in South Africa which, in 1948, made racial segregation and economic oppression of Black South Africans legal under apartheid. Among his published works was a volume of The Young Traveller series from the publishing house of J. M. Dent. Delius’s The Young Traveller in South Africa (1947), like other books in the series, involved British children visiting a country and meeting its people, learning its industries, and observing its culture. Although Dick Wisley, the main British protagonist, stays with white South African relations, Delius ensures that Dick meets many Black individuals and communities, and he uses these encounters to comment negatively on the South African government. When, for example, Dick visits a Bantu township and is shocked by the poverty and the fact that families are torn apart by the system, his cousin Alice says that ‘Johannesburg is responsible and so is the rest of South Africa’ (52). Delius also points out how white South Africans deem the Black South Africans uncivilised, but that the Bantu had produced sophisticated irrigation systems and folk-lore that Dick recognized as the origin of Brer Rabbit stories. Whereas Amelia Opie’s abolitionist writing earned her renown and success, Delius was exiled for his anti-government writing and a subsequent edition of his Young Traveller in South Africa, published in 1959, was edited to soften Delius’ criticism of the South African government and its people.

Writing about apartheid proved difficult for many authors while they were in South Africa. Toeckey Jones attended the University of Witwatersrand, known for its anti-apartheid protests and activities; he became a journalist after university but left the country in 1971 rather than remain under the apartheid system. This was a choice many white activists made, as they had the freedom to travel that nearly all of their Black counterparts did not. Jones wrote about South Africa under apartheid in Go Well, Stay Well (1979), told from the viewpoint of white teenager Candy, who befriends a Black teenager, Becky, from Soweto. Candy struggles with the resistance she faces from her liberal but cautious parents, and with her own fears—she admits to Becky that she doesn’t want to see a Black government in power, because she thinks they would take revenge on white people (156). Becky appreciates her honesty, and somehow the two remain friends. The book ends with the two going on holiday in Swaziland—Candy tells her mother that she ‘needs it, to help me find out what I really think and feel’ (189). Jones suggests that it is impossible for white people to escape the normality of apartheid while under the system itself. This is something that Beverley Naidoo discusses in the 1995 edition of her first novel, Journey to Jo’burg, about Black South African children living under apartheid. Naidoo based the story in part on the experience of the woman who looked after her while her own children lived (and eventually died) far away in a township. Looking back, Naidoo commented, ‘I still feel very angry about how the racism of the white society stopped me and other white children from really seeing and understanding what was going on’ (142). Her book, unlike Toecky Jones’, focuses on the experience of Black South Africans to create empathy in the reader, but it does not (except in her additional commentary, outside the main narrative) suggest the complexities of a white writer telling the story of Black characters to readers who have no direct experience of the situation described. Naidoo’s book successfully contributed to raising awareness about the apartheid system for young British readers, but as with abolition this awareness was from a distance, and the book was banned in South Africa itself until the fall of apartheid. It was not until 2000 that Naidoo wrote a story about injustice that was published in the country of the injustice; The Other Side of Truth exposed the corrupt government in Nigeria, but also the problematic refugee and asylum system in the UK. This book won the Carnegie Medal in 2001.

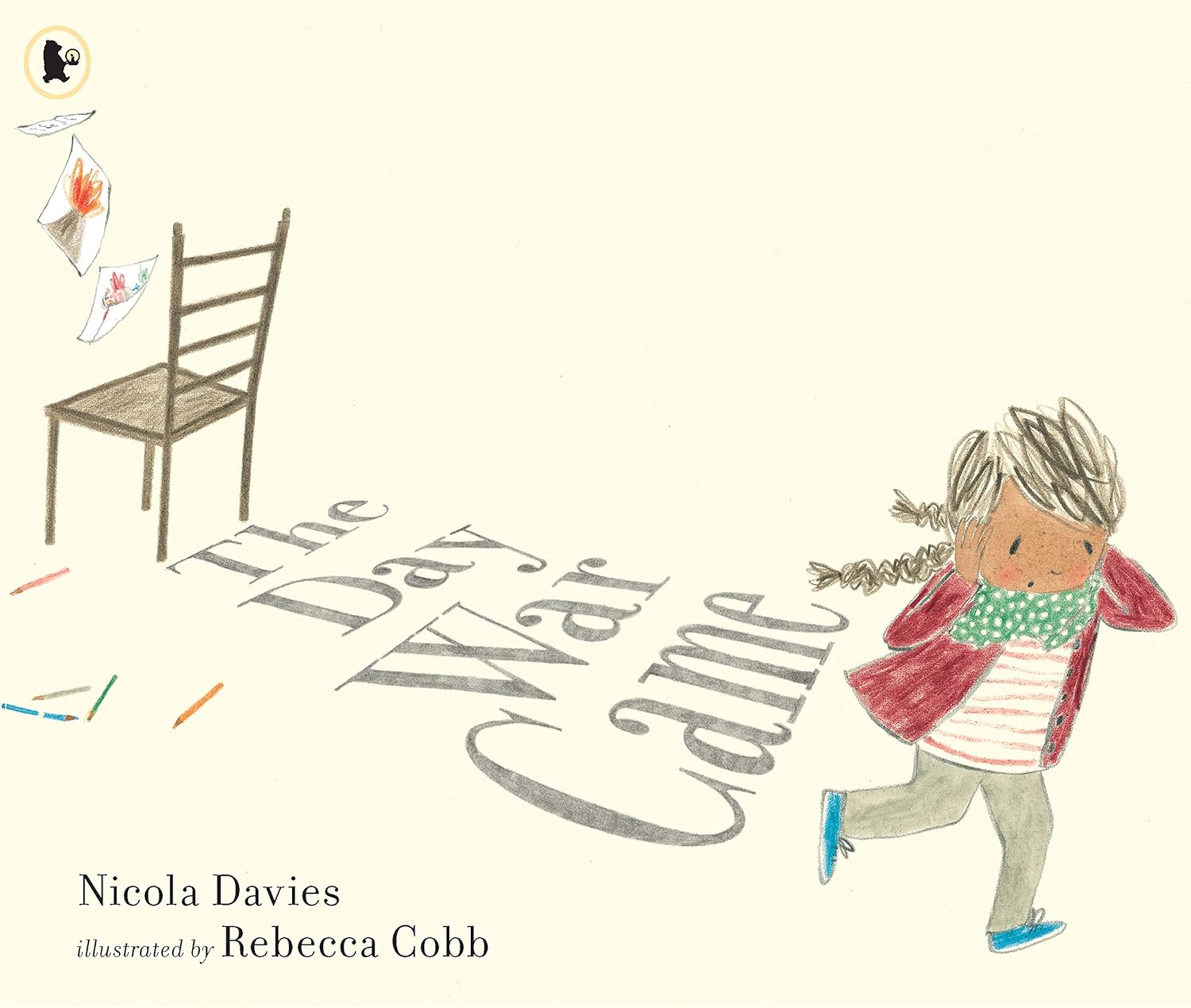

The Day The War Came (2019), written by Nicola Davies and illustrated by Rebecca Cobb is a recent picturebook, endorsed by Amnesty International UK, that can be said to be an example of witness literature. As an afterword explains, Davies initially wrote the text as a poem in response to the UK government’s 2016 refusal to give sanctuary to 3,000 unaccompanied child refugees. We see both the effects of war and the indifference of adults towards refugees from the point of view of the child protagonist. It is children who bring chairs from home to accommodate the child refugees; their chairs represent a warmth and sense of home that the adults of the story were reluctant to offer.

In Four Feet, Two Sandals (2007), written by Karen Lynn Williams and Khadra Mohammed and illustrated by Doug Chayka, it is the sharing of sandals in a refugee camp on the Afghanistan-Pakistan border that is the motif of care and hope. When Lina’s name appears on the list of people granted access to America, and Feroza’s does not, they take one sandal each and vow to be reunited. The story ends on a note of hope, tempered with realism.

In My Garden Over Gaza (2022), written by Sarah Musa and illustrated by Bazlamit, Noura’s commitment to her father’s rooftop garden, in the face of drones spraying herbicides, again offers a tale of hopeful witnessing. Noura expresses fear and anxiety but also warmth and resilience. We witness her struggle to maintain a garden, so often employed as a symbol of childhood flourishing.

Karen Sands-O’Connor is the British Academy Global Professor for Children’s Literature Newcastle University. Her books include Children’s Publishing and Black Britain 1965-2015 (Palgrave Macmillan 2017).

Darren Chetty is a teacher, doctoral researcher and writer with research interests in education, philosophy, racism, children’s literature and hip-hop culture. He is a contributor to The Good Immigrant, edited by Nikesh Shukla, and the author, with Jeffrey Boakye, of What Is Masculinity? Why Does It Matter? And Other Big Questions. He tweets at @rapclassroom.

Books mentioned:

Children of the Stone City, Beverley Naidoo, HarperCollins Children’s Books, 978-0008471774, £7.99 pbk

Go Well, Stay Well, Toeckey Jones, PublishNation, 978-1916696532, £10.99 pbk

Journey to Jo’burg, Beverley Naidoo, HarperCollins Children’s Books, 978-0007263509, £7.99 pbk

The Other Side of Truth, Beverley Naidoo, Puffin, 978-0141377353, £7.99 pbk

The Day The War Came, Nicola Davies, illus Rebecca Cobb, Walker Books, 978-1406382938, £7.99 pbk

Four Feet, Two Sandals, Karen Lynn Williams, Khadra Mohammed, illus Doug Chayka, Eerdmans Books for Young Readers, 978-0802852960, £10.99

My Garden Over Gaza, Sarah Musa, illus Saffia Bazlamit, 9781989079256, £10.99

**

Nadine Gardimer, (2002) Testament of the Word

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2002/jun/15/fiction.nadinegordimer

Ian King, (2007) What is Literature of Witness? https://www.awpwriter.org/magazine_media/writers_notebook_view/66/what_is_literature_of_witness

Beverley Naidoo, (2004), Out of Bounds: ‘Witness Literature’ and the Challenge of Crossing Racialised Boundaries,

https://beverleynaidoo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/boundsWitnessLiterature-1.pdf

Beverley Naidoo, (2023) https://booksforkeeps.co.uk/article/witness-literature/