This article is in the Beyond The Secret Garden Category

Beyond the Secret Garden: Magic

In the latest in their long-running Beyond the Secret Garden feature, examining the representation of black, Asian and minority ethnic voices in British children’s literature Darren Chetty and Karen Sands-O’Connor look at magic and who gets to wield it.

The first English translation of 1001 Nights (variously titled as Arabian Nights, Arabian Nights’ Entertainment, and 1001 Arabian Nights) appeared in 1706, based on the French version by Antoine Galland. Although published for adults, illustrated and pantomime versions quickly became part of British children’s experiences, ensuring that orientalist stereotypes of the magical, mysterious ‘East’ were ingrained in the British consciousness from childhood. In the early nineteenth century, for example, Charlotte Brontë’s juvenilia were peppered with magic carpets and genii, and reference to Arabian Nights can be found in her most famous novel, Jane Eyre (1847). Charles Dickens has Ebeneezer Scrooge envisioning Ali Baba when the Spirit of Christmas Past takes him back to his student days and favourite books. Later authors play on this sense of ‘the East’ as a magical and almost imaginary place—Kipling’s Just-So Stories (1902) is a prime example, with its camel whose hump is lifted ‘by the sun and the wind and the Djinn in the garden’ and its Parsee whose outfit reflects ‘more-than-oriental splendour’.

‘Oriental’ magic enters Britain in children’s books as well, perhaps most famously in Frances Hodgson Burnett’s A Little Princess (1905), where Sara Crewe’s miserable life as a servant in a girl’s boarding school is transformed by ‘the Magic’ of Ram Dass, an Indian servant who lives next door. Ram Dass’s magic is actually just the ability to move furniture and food from his attic dormer to Sara’s, but Sara insists on framing his kindness in terms of magical ability designed to restore her to her original status as ‘a little princess’. This hierarchy of white character served by magical ‘oriental’ figure would be revisited by the writer Robert Leeson in his Third-Class Genie (1975), in which Alec Bowden is happy to use a genie’s power until he realizes that he has enslaved Abu—who is not the ‘Arabian’ he expected but a Black African.

Although Abu is a genie, most magic connected with people of African origin in British children’s literature has historically been dark magic. H. Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines (1885) and She (1887) exemplify white versions of dark African magic. In the twentieth century, a Hollywood-inspired version of the African and Afro-Caribbean religion of Voodoo became a common feature—and, for British characters, fear—in children’s literature about the Caribbean. Following Hollywood movies such as White Zombie (1932), Black Moon (1934) and I Walked with a Zombie (1943), British children’s literature from comics (Tiger Tim’s 1948 annual had ‘Alan’s white magic’ saving white British Alan and his sister Sheila from violence and superstition of the Black ‘natives’ of Coral Isle) to novels. Philip Pullman’s Broken Bridge (1990) uses similar tropes; Ginny, the daughter of a white British father and Black Haitian mother, at first turns to Voodoo gods to find her mother, but eventually realizes that her true mission is to forget her mother and heal her white family who had become estranged because of Ginny’s father’s marriage.

The 21st century has seen Harry Potter become one of the highest grossing franchises of all time. The huge success of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone and the books and the eight films that followed, not only shaped the imagination of many young readers in the USA and elsewhere about life in Britain, it also shaped ideas about who did and did not get to be magical. In 2023 the video game Hogwarts Legacy was released onto the market. By 2016, the value of the franchise was estimated at $25 billion dollars. That same year, in his chapter in The Good Immigrant, Darren described the Potter series as; ‘a story that has so much to say about racism on an allegorical level at the same time depicts people of colour as marginal without exploring their marginalisation.’ This point was also made in the 2015 YouTube film Every Single Word Spoken by a Person of Color in the Entire ‘Harry Potter’ Film Series, made by Dylan Marron which runs to just 6 minutes and eighteen seconds. In a poem published in The Working Class (2018) Darren wrote, ‘I hope that someone / Opens a / Black Wizards’ Supplementary School / Very soon’ (p305), attempting to make connections between issues in the Potter books, the education system, and children’s publishing.

However, the last few years has seen an explosion of children’s and young adult fiction where Black and other racially minoritised people are depicted as magical – and in non-stereotypical ways.

The Jhalak prize shortlisted Mia and the Lightcasters (2022) by Janelle McCurdy is the first in a series in which Mia encounters the shadowy Reaper King – a creature of nightmares. Mia’s whole life changes when a mysterious cult captures the protectors of her city – including her parents and their magical creatures made of shadow and stars, the umbra. In The Thief of Farrowfell (2023) by Ravena Guron, twelve-year-old Jude Ripon, from a family of magic-stealing masterminds, decides to steal valuable magic to prove herself, leading to a series of comedic twists and turns.

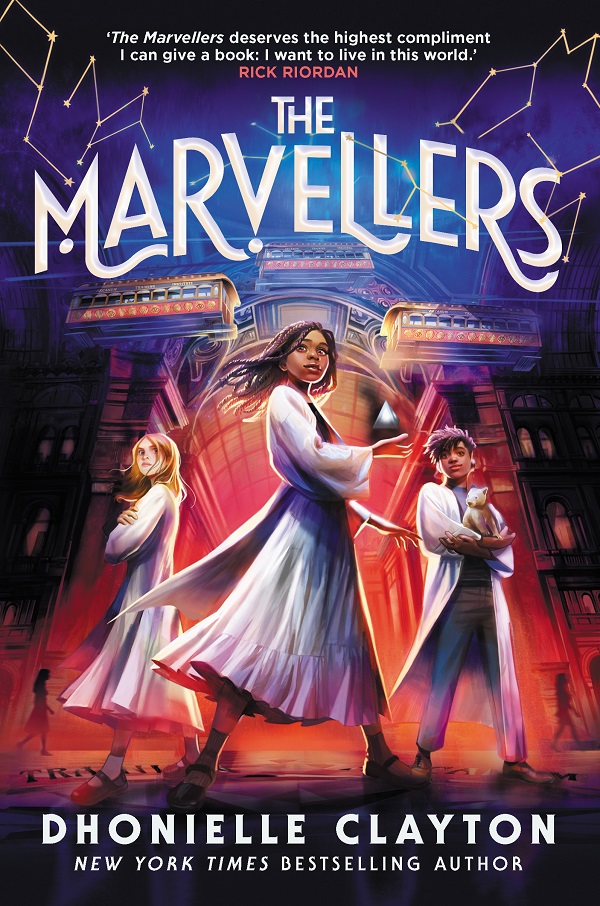

Many of the other recent magical books have continued the long tradition of stories set in fantasy worlds but speaking to real-world events. In B.B. Alston’s Amari and the Night Brothers (2021) Amari learns of her own magical powers as she searches for her brother Quinton who has disappeared from their home in the low-income housing projects, after receiving full scholarship offers to two different Ivy League schools. The Marvellers (2022) shows a diverse cast of characters attending a school of magic in the clouds. In a recent interview with Darren, author Dhonielle Clayton said, ‘Publishing The Marvellers could be seen as an act of aggression and critical commentary on the Harry Potter universe because it includes all the children J.K. Rowling marginalized, stereotyped, and frankly, forgot. But I’m not writing to be in conversation with her or her world, though it may seem like it and I can’t seem to escape the comparisons. I’m writing for the children that are not seen by her, and that are not seen in general.’ There are clear echoes of the Jim Crow era and the school desegregation that followed the landmark Brown vs Board of Education case. Angie Thomas’ Nic Blake and The Remarkables (2023) draws on historical events, including the Atlantic slave trade as well as elements of African American folklore.

City of Stolen Magic by Nazneen Ahmed Pathak (2023) set in 1855, explores the British rule of India. Indian magic is being stamped out and people born with magic are being taken across the sea by the ‘Company’. Cultural imperialism and the system of indentureship are explored, while the action shifts from Bengal to London. Gita Ralleigh’s middle-grade novel The Destiny of Minou Moonshine (2023) is set in the Queendom of Moonlally, an alternate Colonial India that is ruled by a tyrant.

Tọlá Okogwu’s Onyeka and the Rise of the Rebels (2023) continues the series that began with Onyeka and the Academy of the Sun (2022). Onyeka is a British-Nigerian girl who discovers her curls have psychokinetic abilities and is sent to the Academy of the Sun, a school in Nigeria where Solari – children with superpowers – are trained.

E.L Norry’s Fable House (2023) is set in a children’s home for many of Britain’s ‘Brown Babies’ – children born to African-American GIs and white British women following the Second World War. Emma Norry, who herself grew up in the care system in Wales, combines this historical story with Arthurian legend in a narrative that sees Heather set off on a quest to rescue the children of Fablehouse.

Future Hero: Race to Fire Mountain (2022) is the first in an Afrofuturist series by Remi Blackwood, the name of a team of writers led by Jasmine Richards. Jarell finds a magical mirror and an exiled God working as a barber in his cousin’s barbershop, and discovers that he is the hero that those in a distant land called Ulfrika have been waiting for.

Karen Sands-O’Connor is the British Academy Global Professor for Children’s Literature at Newcastle University. Her books include Children’s Publishing and Black Britain 1965-2015 (Palgrave Macmillan 2017).

Darren Chetty is a teacher, doctoral researcher and writer with research interests in education, philosophy, racism, children’s literature and hip-hop culture. He is a contributor to The Good Immigrant, edited by Nikesh Shukla and the author, with Jeffrey Boakye, of What Is Masculinity? Why Does It Matter? And Other Big Questions. He tweets at @rapclassroom.

Books mentioned:

Mia and the Lightcasters by Janelle McCurdy, Faber & Faber, 978-0571368433, £7.99 pbk

The Thief of Farrowfell by Ravena Guron, Faber & Faber, 978-0571371174, £7.99 pbk

Amari and the Night Brothers by B.B. Alston, Farshore, 978-1405298193, £7.99 pbk

The Marvellers by Dhonielle Clayton, Piccadilly Press, 978-1800785472, £7.99 pbk

Nic Blake and The Remarkables by Angie Thomas, Walker Books, 978-1529506549, £7.99 pbk

City of Stolen Magic by Nazneen Ahmed Pathak, Puffin, 978-0241567487, £7.99 pbk

The Destiny of Minou Moonshine by Gita Ralleigh, Zephyr, 978-1804545478, £14.99 hbk

Onyeka and the Academy of the Sun by Tolá Okogwu, Simon and Schuster, 978-1398505087, £7.99 pbk

Fable House by E.L Norry, Bloomsbury, 978-1526649539, £7.99 pbk