This article is in the Beyond The Secret Garden Category

Beyond the Secret Garden: Gypsy, Roma and Traveller representation in Children’s Literature

In the latest in our Beyond the Secret Garden series, Darren Chetty and Karen Sands-O’Connor examine the way the Gypsy Roma and Traveller communities are represented in children’s literature.

Gypsy, Roma and Travellers are identified in Britain as minority ethnic groups in the Race Relations (Amendment) Act (2000). The Act places a general duty on all schools and public authorities to eliminate unlawful racial discrimination, promote equality of opportunity and promote good relations between people of different ‘racial groups’. Despite this, in April 2023, The Guardian reported that The Evidence for Equality National Survey showed that Gypsy Roma and Traveller groups experience ‘extremely high levels of racial assault, poor health, precarious employment and socioeconomic deprivation’.

In keeping with this, the national charity Friends, Families and Travellers identify their main areas of work as ‘Health, Hate, Accommodation and Education’. Gypsy Roma and Traveller History Month (GRTHM) was established nationally in June 2008 to raise awareness of the history and discrimination faced by Gypsy Roma and Travellers (GRT), celebrating their cultures and educating against negative stigmas. The term ‘Gypsy’ is contentious; often regarded as a slur when used from people outside the community, rejected by many Romani people, but used by some.

The ‘Gypsy Caravan’ has been used throughout children’s literature as a symbol of freedom and adventure, but also of being outside the law. Toad in Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows (1908) tries to lure Mole and Rat away from the river in his, a plan which ends in the double disaster of a crashed caravan and Toad’s obsession with (stolen) motor cars. The main character in Roald Dahl’s Danny, the Champion of the World (1975) lives with his father in a Gypsy caravan where they poach pheasants with drugged raisins from a nouveau-riche landowner. Neither Toad nor Danny’s father are on the right side of the law, but the magnificence of the Gypsy caravans lures the other characters—and readers—to a fascinated conspiracy with them.

Actual Romany/i people and Travellers are viewed with more suspicion in children’s literature, however. They are villains in Enid Blyton’s Five Go to Mystery Moor (orig. pub. 1954). Although the revised version, published in 1991 (Hodder), has exchanged the word ‘gypsy’ for the term ‘traveller’, the revision cannot erase the way that Blyton depicts them or the white, middle-class Famous Five react to them. Blyton depicts adult Traveller men (Traveller women only appear briefly) as abusers of children, horses, and dogs as well as thieves passing off forged American dollars. The one ‘good’ Traveller character, Sniffer, is described by tomboy George as ‘quite disgusting’ (p51) for not using a handkerchief, but he redeems himself by saving George and Anne from his father and the ‘gang’ of Travellers. George asks Sniffer what he wants in return, and Sniffer requests a bicycle, home, and a chance to go to school—in short, to leave the caravan life. For Sniffer, the caravan is not freedom but a prison, while true freedom can only be found in stable homes and educations.

In the 1960s and 1970s, a number of books featuring Traveller children were published, possibly in response to the Plowden Report (1967) which argued that Travellers were Britain’s most educationally deprived group. Roger Clive Kemp, a teacher educator, produced Derrick and Dora Visit Saint Ives (1967), which tells the story of Derrick and Dora Romany, two ‘very lucky children’ (p3) who live in a ‘grand, ornately decorated caravan’ that lets them travel the world. They go on their own adventure (without the caravan) to the seaside, and eat meat pies in Cornwall and buy a present for their parents. In 1973, the volunteer-run West Midlands Travellers’ School was formed; they created a series of reading books in consultation with members of the Traveller community. Stories such as ‘The Big Dog’ and ‘Help, help—Fire!’ (both 1976) centered on real-life concerns for Traveller children.

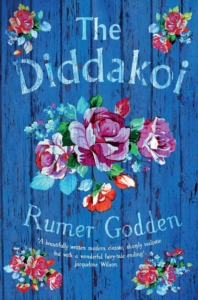

Accommodation has remained a focus for many white authors writing about Traveller children with plots framed around this perceived tension between caravan life and stability. Rumer Godden’s The Diddakoi (1972), which won the Whitbread Children’s Book Award, begins with Kizzy, a ‘half-gypsy’ or Diddakoi, living with her grandmother in an old-fashioned Gypsy wagon on the wealthy landowner’s paddock. She goes to school, but dislikes it because the children make fun of her and the adults mistrust her, calling her ‘wild’ and ‘savage’. When her grandmother dies, the wagon is burned as part of the funeral custom, and Kizzy must live in a house. Godden’s story is essentially a fairy tale; Kizzy ends up being adopted by the wealthy landowner who has rescued the gypsy wagon from complete destruction, repainting and furnishing it for her as a playhouse. Kizzy is thus given both worlds, a stable home and a caravan, a white upper-class life and a Gypsy one. Anthony Masters’ Travellers’ Tales (1990), which he wrote after working with Traveller children for many years in schools, depicts a girl who doesn’t have Kizzy’s choices. Prim, who (like Sniffer) longs for school, concludes that for girls, the ‘Travellers’ way of life … could also be a prison’ (p154) as her future was not in education but in marriage and motherhood.

between caravan life and stability. Rumer Godden’s The Diddakoi (1972), which won the Whitbread Children’s Book Award, begins with Kizzy, a ‘half-gypsy’ or Diddakoi, living with her grandmother in an old-fashioned Gypsy wagon on the wealthy landowner’s paddock. She goes to school, but dislikes it because the children make fun of her and the adults mistrust her, calling her ‘wild’ and ‘savage’. When her grandmother dies, the wagon is burned as part of the funeral custom, and Kizzy must live in a house. Godden’s story is essentially a fairy tale; Kizzy ends up being adopted by the wealthy landowner who has rescued the gypsy wagon from complete destruction, repainting and furnishing it for her as a playhouse. Kizzy is thus given both worlds, a stable home and a caravan, a white upper-class life and a Gypsy one. Anthony Masters’ Travellers’ Tales (1990), which he wrote after working with Traveller children for many years in schools, depicts a girl who doesn’t have Kizzy’s choices. Prim, who (like Sniffer) longs for school, concludes that for girls, the ‘Travellers’ way of life … could also be a prison’ (p154) as her future was not in education but in marriage and motherhood.

More recent books by white authors speculated on what being a part of GRT culture means; we often see characters who are either exotic and mysterious or tragic and trapped; or a combination of both of these tropes. Elizabeth Arnold’s Gypsy Girl Trilogy (1995-7) makes Freya, the main character, a magical twelve-year-old loved by all, who can use charms and spells; it was made into a CITV series in 2001. In Gaye Hiçyilmaz’s Girl in Red (2000) Emilia, is a Romanian Gypsy who has arrived in the UK as a refugee. It is striking that she is not heard for the first half of the book. Instead, we see her through the eyes of Frankie, a Year 9 boy who is entranced by her long blonde plaits, and long red skirt. Frankie’s mother leads a campaign to protest the arrival of the Roma people in their working-class community. Though Frankie learns something of the history of discrimination and oppression toward Roma people and rejects his mother’s views, his concern for Emilia does not appear to extend toward the rest of her community. Emilia, he says, ‘wasn’t like the others’ (p135). Indeed, he and his classmates view her as like ‘a princess or a super model’ (p95).

Pavee and the Buffer Girl (2017) is a story for teenagers written by Siobhan Dowd and illustrated by Emma Shoard and originally appeared as a short story in Skin Deep, a 2004 anthology published by Puffin and edited by Tony Bradman. Set in Ireland, the story includes racial abuse and racial violence towards Jim, a Traveller accused by classmates of stealing a CD. Jim meets Kit, who ‘takes him under her wing’, teaching him how to read. The story ends with Jim’s family fleeing Ireland. Dowd writes as an outsider but one with some knowledge of Irish Traveller communities gained through her postgraduate research.

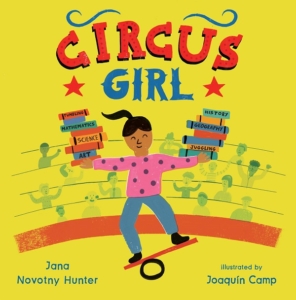

The theme of education appears in a number of picture books with Traveller characters. Tom’s Sunflower (2015), written by Hilary Robinson and illustrated by Mandy Stanley, focuses on dealing with parental break-up. The book is part of the Copper Street series of books dealing with issues and reviewed by experts. The story also includes Skye and Amber who ‘move about a lot with a travelling theatre’. Their bedroom is shown to be colourful and cosy but, we are told, Amber ‘always had a wobbly tummy … when she had to start a new school again.’ In Circus Girl (2019), written by Jana Novotny Hunter and illustrated by Joaquin Camp, Sky combines her love of learning circus skills with her love of learning at school and doing her homework.

The theme of education appears in a number of picture books with Traveller characters. Tom’s Sunflower (2015), written by Hilary Robinson and illustrated by Mandy Stanley, focuses on dealing with parental break-up. The book is part of the Copper Street series of books dealing with issues and reviewed by experts. The story also includes Skye and Amber who ‘move about a lot with a travelling theatre’. Their bedroom is shown to be colourful and cosy but, we are told, Amber ‘always had a wobbly tummy … when she had to start a new school again.’ In Circus Girl (2019), written by Jana Novotny Hunter and illustrated by Joaquin Camp, Sky combines her love of learning circus skills with her love of learning at school and doing her homework.

Informed, rounded depictions of Gypsy Roma Traveller characters are still too rare in children’s literature in the UK. The work of Richard O’Neill, often in collaboration with other writers and illustrators, deserves special mention for changing the literary landscape in this regard. O’Neill, his website tells us, ‘was born and brought up in large traditional, fully nomadic Romani Gypsy family, travelling throughout the North of England and Scotland. His roots are also to be found in the coal mining communities of the North East having family mem bers who worked down the pits.’ This heritage is explored in Polonius the Pit Pony (2018), illustrated by Feronia Parker Thomas and published by Child’s Play, in which Polonius meets horses that are part of a Traveller family, and ultimately helps them, showing that being small is not a disadvantage when you are determined.

bers who worked down the pits.’ This heritage is explored in Polonius the Pit Pony (2018), illustrated by Feronia Parker Thomas and published by Child’s Play, in which Polonius meets horses that are part of a Traveller family, and ultimately helps them, showing that being small is not a disadvantage when you are determined.

O’Neill’s work also engages with the theme of education but avoids contributing to existing negative stereotypes. In The Lost Homework (2019), illustrated by Kirsti Beautyman, Sonny lives on a Traveller site, described as a ‘kushti atchin tan’ (Romany for ‘good stopping place’). He travels with his family to attend a cousin’s wedding, but loses his homework book. Sonny’s world is both traditional – his Aunt teaches him to sew pinnies for market and the local community group are restoring his Grandma’s old vardo, and modern – he teaches a neighbour how to send an email. When he tells the story of the weekend to his class in school, his teacher points out that he covered all the school subjects. O’Neill presents school as very important for Sonny and his family, while highlighting that it is not the only place where learning takes place. Sonny’s teacher believes him, offers him space to tell his story, and makes connections between his life inside and outside school.

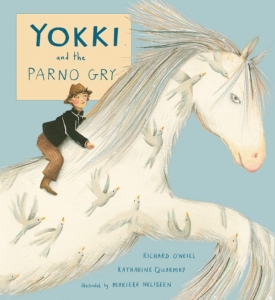

Yokki and the Parno Gry (2016), written by O’Neill and Katharine Quarmby, and illustrated by Marieke Nelissen, explores how Industrialisation has impacted Traveller communities; ‘since we got these new machines I don’t need so many extra hands’ Farmer Tom tells Yokki’s father. The usual camping ground is now fenced off. Yokki is a ‘Traveller boy’. His community live in caravans and tents and keep alive traditions such as spoon-making, paper flower-making, storytelling, and trading and mending kitchen utensils.

In The Can Caravan (2022), illustrated by Cindy Kang, O’Neill celebrates Traveller resilience and independence while showing the whole community, Traveller and non-Traveller, working together. Janie visits a recycling plant with her class and later repairs a neighbour’s caravan using aluminium cans with the help of her classmates and their parents. We are reminded that ‘Travellers have been recycling for centuries’.

In Ossiri and the Bala Mengro (2016) by Richard O’Neill and Katharine Quarmby and illustrated by Hannah Tolson, Ossiri and her family ‘worked hard as “Tattin Folki”, or rag-and-bone people, as the settled people called them.’ Ossiri dreams of being a musician, and though she is discouraged, she makes her own musical instrument. At first the community complain about the noise so she decides to practice. She awakens the ogre, Bala Mengro, ‘huge and as hairy as a Shire horse’. However, the ogre enjoys the music and offers Ossiri first a silver, then a gold chain. A stranger steals the Tattin Folki, but it is found along with the stranger’s boots. O’Neill again celebrates the imagination and creativity of Traveller children.

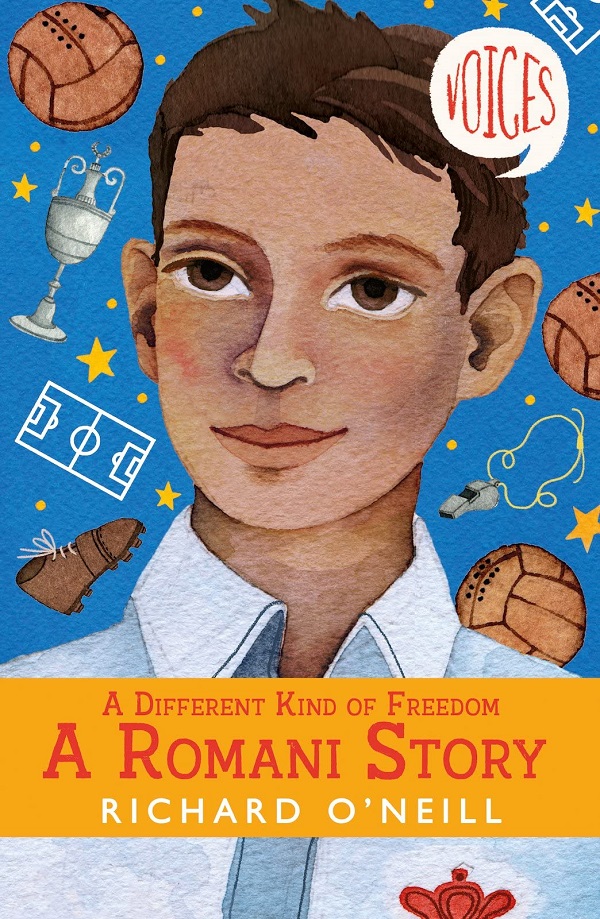

Most recently, Richard O’Neill’s A Different Kind of Freedom: A Romani Story (2023) is the seventh book in the Voices series from Scholastic and is told through the eyes of young Lijah, as he navigates life and discovers football and Rab Howell, who in 1895 became the first Romani footballer to represent England.

O’Neill’s books provide readers with depictions of Romani people who are distinct but not isolated; connected to their heritage and language and viewing both as empowering. He situates innovation within a traditional context where change and continuity are shown to coexist. Romani Traveller people, often absent presences in the earlier examples we have discussed, are shown to be alive and thriving, often in challenging circumstances.

Thanks to teacher and writer, Gemma Bagnall (@MissBprimary), who has done considerable work in raising awareness of the work still to be done in GRT representations in children’s literature.

Karen Sands-O’Connor is the British Academy Global Professor for Children’s Literature at Newcastle University. Her books include Children’s Publishing and Black Britain 1965-2015 (Palgrave Macmillan 2017).

Darren Chetty is a teacher, doctoral researcher and writer with research interests in education, philosophy, racism, children’s literature and hip-hop culture. He is a contributor to The Good Immigrant, edited by Nikesh Shukla, and the author, with Jeffrey Boakye, of What Is Masculinity? Why Does It Matter? And Other Big Questions. He tweets at @rapclassroom.

Books mentioned:

The Wind in the Willows, Kenneth Grahame (1908), various editions

Danny, the Champion of the World, Roald Dahl (1975), Puffin, 978-0141365411, £7.99 pbk

Five Go to Mystery Moor, Enid Blyton (1954/91), Hodder Children’s Books, 978-0340681183, £6.99 pbk

Derrick and Dora Visit Saint Ives, Clive Kemp (1967), O/P

The Diddakoi, Rumer Godden (1972), Macmillan, 978-0230769892, £6.99 pbk

Travellers’ Tales, Anthony Masters (1990), O/P

Gypsy Girl Trilogy, Elizabeth Arnold (1995-7), O/P

Girl in Red, Gaye Hiçyilmaz (2000), O/P

Pavee and the Buffer Girl, Siobhan Dowd, ill. Emma Shoard (2017), Barrington Stoke, 978-1781128794, £7.99 pbk

Tom’s Sunflower, Hilary Robinson, ill. Mandy Stanley (2015), Strauss House, 978-0957124547, £6.99 pbk

Circus Girl, Jana Novotny Hunter, ill. Joaquin Camp (2019), Child’s Play, 978-1786282972, £7.99 pbk

Polonius the Pit Pony, Richard O’Neill, ill. Feronia Parker Thomas (2018), Child’s Play, 978-1786281852, £7.99 pbk

The Lost Homework, Richard O’Neill, ill. Kirsti Beautyman (2019), Child’s Play, 978-1786283450, £7.99 pbk

Yokki and the Parno Gry, Richard O’Neill and Katharine Quarmby, ill. Marieke Nelissen (2016), Child’s Play, 978-1846439261, £7.99 pbk

The Can Caravan, Richard O’Neill, ill. Cindy Kang (2022), Child’s Play, 978-1786286147, £7.99 pbk

Ossiri and the Bala Mengro, Richard O’Neill and Katharine Quarmby, ill. Hannah Tolson (2016), Child’s Play, 978-1846439247, £7.99 pbk

A Different Kind of Freedom: A Romani Story, Richard O’Neill (2023), Scholastic, 978-1407199580, £6.99 pbk