Exploring Realms of Imagination at the British Library

A visit to the British Library’s new exhibition, Fantasy: Realms of Imagination will be a must for many Books for Keeps readers. Tanya Kirk, Lead Curator of the exhibition gives us a guided tour in this article.

Fantasy: Realms of Imagination is a major exhibition at the British Library, exploring the whole history of the Fantasy genre – from its origins in the oldest forms of storytelling right through to the proliferation of fan culture today. Although Fantasy is often thought of as a 19th- or 20th-century genre, the roots are far older and can be found in historic forms of storytelling, like fairy and folk tales, or epics and quest narratives. Modern Fantasy continues to draw on these narratives for inspiration, and to rework them in new and exciting ways. Our exhibition sheds light on the historic threads that run through Fantasy, but demonstrates that it is anything but stuck in the past. Whilst the core of our own collection is books and manuscripts, we were really keen to display many different formats to show the wide influence of Fantasy. Visitors will be able to see original artwork, film and TV props, costumes and clips, alongside tabletop and video games.

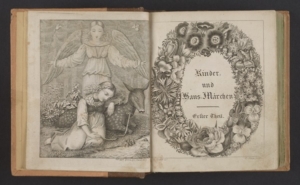

Fantasy is perennially popular as a children’s literature genre, and some of us will have been introduced to it via fairy and folk tales at a very young age. Many of their recurring themes – such as enchantments, transformations, wishes and the supernatural – anticipate later Fantasy writing. There is also plenty of mischievousness – and even darkness – in fairy stories which certainly inspired Fantasy creators. On display we have an early edition from 1819 of Kinder- und Haus-Märchen (Children and household tales) by the Brothers Grimm; a beautifully rich illustration of the Slavonic folkloric figure Baba Yaga by the artist Ivan Bilibin from 1901; and the manuscript of Alan Garner’s seminal 1967 novel The Owl Service, which draws on the early Welsh folk stories in the Mabinogion. We also feature documents from the archive of Jamaican writer James Berry, who penned a collection of stories called Anancy-Spiderman (1983) inspired by the tales he had heard in his childhood ‘in moonlight or in dim paraffin lamplight, during rain and storm winds’ of the trickster hero who could transform into a spider.

Another section of the exhibition looks at the history of world-building; the creation of detailed and believable imaginary worlds, by means of invented geographies, histories, languages, cultures, creatures and laws of physics. This features some of the British Library’s greatest treasures, including tiny books handwritten by the Brontë siblings in childhood, describing their imaginary land of Glass Town. Paracosms – invented childhood worlds of this nature – can be a fascinating outlet for creativity and pure imagination. The exhibition features Fantasy stories ‘The Spell’ and ‘The search after happiness’ by Charlotte Brontë – in which enchantments and magical portals play important roles – and a map and historical account of Glass Town by Branwell Brontë.

The manuscripts are shown together with E. Nesbit’s handwritten draft of her 1910 novel The Magic City, a perhaps lesser-known work by Nesbit in which the hero of the story, Philip, builds a tabletop city out of household objects and toys. Subsequently he and his friend Lucy find themselves inside the city itself where Philip assumes the role of the ‘Deliverer’, rescuing the city by taking on quests including slaying a clockwork dragon. The manuscript survived because a librarian at what was then Woolwich Public Library had written to Nesbit in 1913, expressing admiration for her work, and she had replied saying perhaps the Library would like to keep the manuscript of one of her novels. She wrote ‘This will probably be more interesting to the next generation than to this… If anyone ever should be interested in this M.S. [manuscript] the most interesting thing will be the comparison of the notes with the finished work. The comparison will show how a story develops itself, and how far it something travels from the author’s original intention.’

The exhibition features one section entirely given over to children’s literature, and this is called ‘Gateways and Thresholds’ – an exploration of

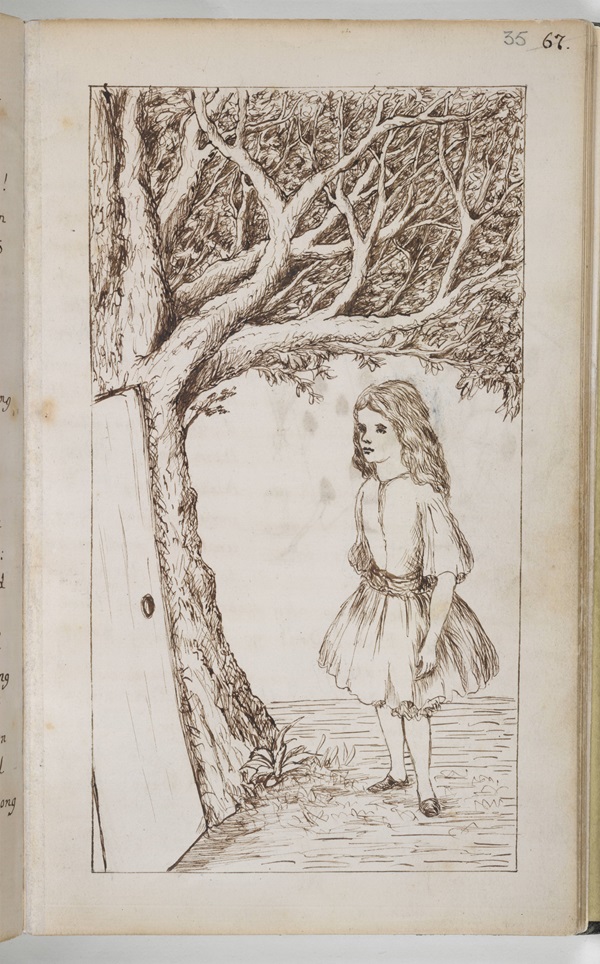

portals. Portals allow the reader to experience an imagined world through the eyes of a protagonist and compare it with our own. Perhaps that is why they are particularly popular in children’s fiction, firing the imaginations of young readers for whom the discovery of a doorway into another reality seems a real possibility. Portals first appeared in children’s books in the 19th century, with writers such as George MacDonald, Charles Kingsley and E. Nesbit all early adopters of the trope. At the British Library we are lucky enough to hold in our collection the original manuscript of Alice’s Adventures Under Ground (1864), the handwritten story that would eventually be published as Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) – sometimes called the first children’s portal Fantasy. The author’s original illustrations may be unexpected for those who grew up with the distinctive Tenniel version – and perhaps even more surprising are the pen-and-ink artworks by Mervyn Peake for his illustrated version of the Alice books, which we show alongside. Peake’s grumpily surreal White Rabbit, depicted marching down the rabbit hole, is extremely characterful.In early portal stories, the portal was often a straightforward gateway to a different world, appealing to the child reader’s sense of adventure and their desire to explore, or, in the case of the Alice books, occasionally as a mechanism for reflecting and mocking the ‘silly rules’ of adult society. But in the 20th century and beyond, portals have often acted as metaphors, with thresholds representing stages of growing up. We are delighted to have borrowed from Neil Gaiman for the exhibition his original manuscript for the novel Coraline (2002). The young heroine of the story finds a passage into a sinister alternative version of her own reality, ruled over by the terrifying ‘Other Mother’, who has black buttons for eyes. Like Lewis Carroll in the Alice books, Gaiman makes the world beyond the portal a twisted version of our own – but far more than Carroll does with Alice, Coraline’s courage is emphasised as she overcomes her fears and enters the realm of the Other Mother to rescue her real parents.

As a librarian, I was delighted to be able to display volumes from the Japanese manga series Honzuki no gekokuj.: Shisho ni naru tame ni wa shudan o erande iraremasen. (Ascendance of a Bookworm: I’ll Stop at Nothing to Become a Librarian), by Kazuki Miya and Suzuka in 2013-17. This is an example of a subgenre of Fantasy called isekai: stories in which the main protagonist, often a teenager, becomes trapped in another world, sometimes by dying and being reborn. Ascendance of a Bookworm follows the adventures of Urano Motosu. In the story she is crushed to death under a pile of books and reborn into a world where books are extremely scarce and has to recreate them herself. The roots of isekai lie in Japanese folk tales, but they sometimes feature a quest narrative similar to the plotline of a video game – a clear demonstration of how Fantasy is constantly drawing on influences old and new to create something transformative.

There can also be a bittersweet element to portal Fantasy – such as in Philippa Pearce’s Tom’s Midnight Garden (1958), a ‘timeslip’ story in which the portal takes the protagonist into a different period of history – a popular trope from the mid-20th century onwards. The exhibition includes an original illustration by Susan Einzig, as reproduced in the first edition of the novel. It shows the main character Tom entering a magical garden when a clock strikes 13. He befriends a girl whom he discovers is from the Victorian period, coming to the poignant realisation as he witnesses her ageing over repeated visits that we do not stay children forever.

A similar sense of loss and poignancy can be found in Seanan McGuire’s Wayward Children series, the first volume of which is Every Heart a Doorway (2016). The books are set in a special boarding school for children who have previously travelled to other worlds via portals. On returning to our world, they often mourn the other realities where they felt able to be their true selves, and long to return. McGuire uses the idea of the portal and the children’s reactions to explore the trauma of growing up and learning to fit in with our peers.

Of course, we couldn’t have a Fantasy exhibition without featuring Diana Wynne Jones, who returned to the idea of a multiverse and the portals within it many times in her books. On display in the exhibition we have the first pages of the original manuscript of her great comic novel The Dark Lord of Derkholm (1998), which satirises portal Fantasy. The story is set in a High Fantasy world besieged by groups of tourists travelling from our world. Expecting the full Fantasy experience, they force the inhabitants to take turns playing stereotypical roles. In an attempt to bring about the end of the tours, senior officials appoint the seemingly incompetent wizard Derk to play that year’s Dark Lord. The novel is filled with Wynne Jones’ wonderfully idiosyncratic touches – several of Derk’s children are griffins, for example, although he is human– and it draws on her own earlier satirical Fantasy travel book The Tough Guide to Fantasyland (1996), which uproariously yet fondly sends up clichés of the genre.

The exhibition runs at the British Library in London to 25 February 2024, and is accompanied by an events programme featuring children’s authors including Philip Pullman and Susan Cooper, and by satellite exhibitions and events programmes in public libraries that are part of the Living Knowledge Network, all across the UK. A book of essays inspired by the exhibition’s themes will be available from the British Library’s shop and other retailers (Realms of Imagination: Essays from the Wide Worlds of Fantasy). It features 20 different perspectives on the genre, including many that will be of interest to children’s literature enthusiasts.