Classics in Short No.142: Walkabout

Brian Alderson goes down under to explore James Vance Marshall’s classic Walkabout.

The upbringing of children

in the deserts of Northern Australia went to a set pattern. First you were in arms, then you were weaned, then you walked with the tribe, learning the features of your land, and then you went walkabout. This was a journey lasting six months or more when you took yourself off alone, learning self-sufficiency among the water-holes and the slim provender that it was needful to find if you were ever to return to the tribe to fulfil the demands of manhood.

It was on such a trip

that the bush-boy of our story (he is given no name) encounters two wholly mysterious beings. They have a whiteish skin colour, unlike his own jet black, and parts of them are draped with garments where he is naked. They are engaged in an incompetent plucking of fruit from quandong trees which they are ravenously eating, but once he has assured himself that they are not ghosts or dangerous he leaves them to their strange devices. Only when they chase after him does he recognize that they do not know what they are doing.

They do know some things though.

They know they are Pete (8) and his sister Mary (13) and that they were on the way from their home in Charleston, South Carolina to Adelaide when their plane crashed and was immolated, killing its pilot and navigator. They know too that Adelaide was to the south of their present position and had just decided to try to walk there. But they did not know that it was 1400 miles away across an unforgiving desert.

In the unlikely event

that the bureaucracy of aborigine tribes appoints assessors of its walkabout candidates, the bush-boy who was meant to be travelling alone, ought to have received extra commendation for now suddenly having to shepherd two human encumbrances, ignorant of his world and of his language, on a trail that was demanding enough for him on his own. The boy Peter though is quick to catch on both to a form of communication and to the foraging arts so that progress is slow but steady.

Calamity arrives

through the veneer of Western ‘civilised’ values with which Mary is imbued. From their first meeting, she has been troubled that their companion is naked and, recalling missionary lectures in South Carolina, she makes a vain effort to persuade him to wear her panties. Acceding to this with some puzzlement the boy decides that it must preparation for some kind of jamboree and, abetted by Pete, he engages in some wild and hilarious dancing. The pants cannot help but suffer and when, as the jamboree ends, the boy confronts Mary he suddenly realizes that she is a lubra, a female, while Mary, in her turn, is terrified to recognize that it is a fact he has only just discovered. For the Aborigine however the sight of Mary’s terror can mean only one thing: that she has seen in his face the terror of Death and that the fates have doomed him to die.

Such is the more than millennial strength

of his culture that there can be no escape for him from the knowledge that his Death is travelling with him. The journey continues, but it is a faltering one, riven by the boy taking a cold which almost seems to confirm the inescapability of his doom. Before he dies though he is able to ‘explain’ to Pete the route that they are following and direction to distant hills where will be the-valley-of-waters-under-the-earth.

The turning point of the novella

comes with the death of the bush boy. The children know no better than to give him a Christian burial far from the customs of his tribe. (In his last days he wondered if they would know to build him a burial platform above the reaches of the beasts of the desert.) Then they set off on the track to the distant hills where the boy had promised they would find food and water.

It is a tough walkabout for them

but Pete trusts the boy’s directions to a given line of hills and there they do find almost as golden a valley as Gluck’s in The King of the Golden River. Ever more skilled in looking after themselves – with Mary now herself accommodated to living naked – there would seem no reason why they might not abandon facing whatever terrible journey might lead them from this place to distant Adelaide and continue living in comparative comfort. Coincidence though will have its way.

Among their recreations

had been the discovery that there was a pipe clay in their valley that, when moistened, could be used to make drawings on rock surfaces along the lakeside. Peter drew some of the wildlife around them but Mary made pictures from her American past, including a very simple four-square house with a door and a window. Peter rather scorned it, but one day, to their astonishment, an Aborigine family came to the other side of the lake and swam across to greet them. It was as friendly a meeting as it was surprising but the paterfamilias spotted the drawing of the house. Apparently a travelled man, he recognised it for what it was and in the sign conversations at which Peter too was adept he explained to the children how they might travel a route to just such a dwelling.

The story leaves them

setting out to what may be their salvation although one must wonder whether the deserts of the bush might not have more to offer than those of the ‘civilisation’ ahead, pants or no pants.

Brian Alderson is founder of the Children’s Books History Society and a former Children’s Books Editor for The Times. His latest book The 100 Best Children’s Books, Galileo Publishing, 978-1903385982, £14.99 hbk, is out now.

Walkabout by James Vance Marshall is published by Puffin, 978-0141359427, £6.99 pbk.

__________

Note: Walkabout was originally published by Michael Joseph in 1959 as a novel, The Children, by James Vance Marshall who also wrote as Donald G.Payne. Its fame spread after the success of a refashioned movie in 1971, where the crux of the story, the boy’s nakedness, was modified. Wouldn’t happen now though, would it?

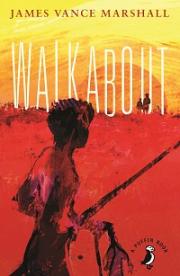

[the accompanying pic by Richard Kennedy is the front wrapper of the Peacock edition of 1963]