Classics in Short No.136: The Last of the Huggermuggers

Brian Alderson travels to Kobboltozo to assesses the first US fantasy adventure.

Anchored in the roads off Portland

Anchored in the roads off Portland

the good ship Nancy Johnson still awaits a signal to join the fleet of American children’s classics. Such forerunners as Hawthorne’s The Golden Age and Tanglewood Tales may have had a setting in the Adirondaks and a narrator at an Ivy League college but for American flavour might just as well have been somewhere like Llandrindod Wells. Certainly before Little Jacket (alias Jackie Cable) went a-sailing no American contemporary had ventured into the realm of fantasy.

Little Jacket

was ship’s boy on an American merchantman making for the East Indies, but after rounding the Cape she was caught in a storm and, like some memorable ships before her, was wrecked on an unknown island. This proved to be the homeland of a race of giants, the Huggermuggers, the last two members of which, childless, were living out the last of their days. Unaware of the kindly temperament of these huge creatures, the shipwrecked survivors took the chance to bring to an end what might have been a very short story by getting themselves providentially rescued by a passing vessel.

After landfall in Java,

Little Jacket meets Mr Zebedee Nabbum who is on commission from Mr P.T. Barnum to collect animals and other exotica for his circus and a plan is hatched to return to the island and abduct the giants. On arrival though the hunters are disarmed by the affability of their prey and foresee a possibility that the Huggermuggers will make a voluntary trip with them back to Portland, New Hampshire. But all is frustrated by a dwarf shoemaker on the island, Kobboltozo, who, hating the giants, is able to activate a curse which brings about their deaths.

The tragedy

(something of a surprise in the annals of fantasy) was delicately handled and prompted an immediate sequel. This was Kobboltozo in which Jackie and Zebedee return to the island a year or two later only to find its remaining dwarfish inhabitants also in a state of decline thanks to the dictatorly proclivities of the shoemaker. Much of the history of these later events is recounted to our heroes by Stitchkin the island’s tailor, and, later, by Hammawhaxo the carpenter, and they dwell on Kobboltozo’s fruitless endeavour to gain the stature of the vanished giants while, in fact, dwindling away to nothing.

The author

of these two engaging and original novellas was one Christopher Pearse Cranch, who confessedly ‘had been born (and educated) with a diversity of talents, wooing too many mistresses’. He was the middle child in a family of thirteen (one of his sisters was to become T.S.Eliot’s paternal grandmother) and early fell under the influence of Emerson. That detracted from his chances of being accepted as a Unitarian minister and he was drawn to both poetry and landscape painting. In both those capacities he resembled a lesser Edward Lear, turning out light verse and caricatures of genial freshness.

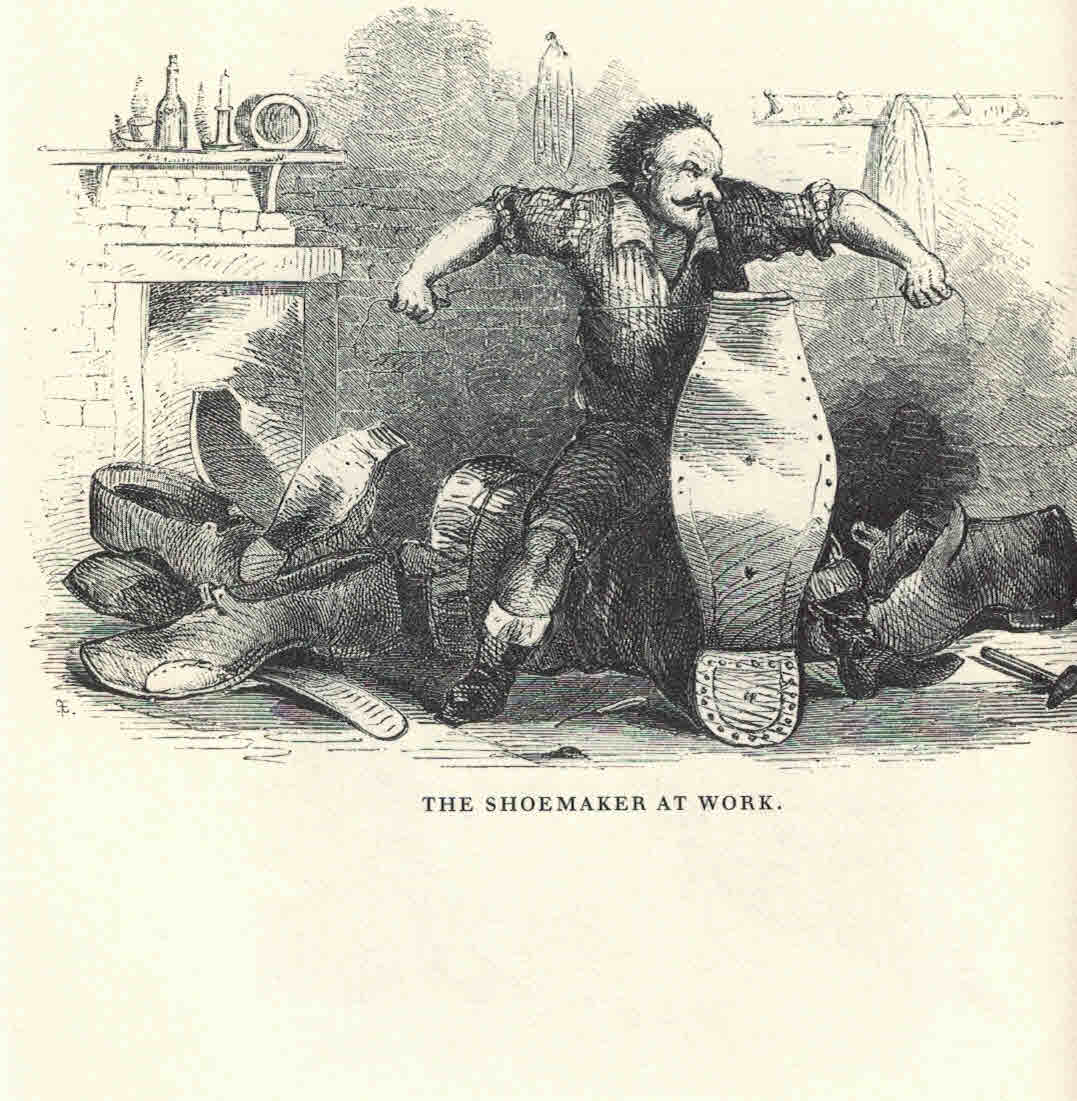

His two children’s books

appeared in 1855 and 1856 and stemmed from a lengthy stay in Europe, where he got to know the Brownings and Thackeray, and they originated as stories told to two of his own four children which gives them a natural storytelling timbre. Good humour abounds (Kobboltozo is but the best of his gift for inventing names); there is no attempt at a crashing moral lesson; and the pathos in depicting the passing of his kindly giants is truer than the factitious deaths so common in Victorian literature. It should also be noted that, like its near contemporary, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, it is one of the first to replicate a distinctive American vernacular, especially in the ruminations of Mr Nabbum. (Here is Zebedee reflecting on a means to possibly pacify a captive giant by giving the critter Rum: ‘I guess he don’t know nothin’ of ardent sperits – [we can] obfuscate his wits – and get him reglar boozy…’) Both books are also illustrated with Cranch’s own excellent illustrations and pictorial initials all of which he drew on the wood, the blocks being shipped home for the American engravers. He seems to have had a hope for publication in England since a footnote in the first book gives a definition of clams ‘for the benefit of little English boys and girls if it should chance that this story should find its way to their country’.

Alas, it did not.

Note:

The Last of the Huggermuggers (but not Kobboltozo) gets only two lines as a ‘border-line’ case in Jacob Blanck’s bibliography Peter Parley to Penrod (1938) and the claim that such fantasy stories were not encouraged by American publishers is borne out by the fact that there are but three entries for such things in Blanck before we get to The Wizard of Oz in 1900. The stories were reprinted on a few occasions but had only a short life and Cranch’s poetry for children found place only in the pages of the periodical St Nicholas. A projected collection, ‘Father Gander’s Rhymes’ (a pre-echo of Denslow’s Father Goose) never materialised. He did attempt to get one other story published: The Legend of Dr Theophilus but that disappeared from view only to re-emerge in the 1980s. It was edited and published alongside its predecessors in Three Children’s Novels by Christopher Pearse Cranch ed. Greta D. Little and Joel Myerson (University of Georgia Press, 1993) , a scholarly edition but one which did no justice to Cranch’s fine illustrations.

Brian Alderson is founder of the Children’s Books History Society and a former Children’s Books Editor for The Times. His book The Ladybird Story: Children’s Books for Everyone, The British Library, 978-0-7123-5728-9, £25.00 hbk, is out now.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin is published by Wordsworth Classics, 978-1840224023, £2.50 pbk