This article is in the Category

Eleanor Farjeon’s ‘books for keeps’

Mystery persists in these rough times as to why the third in what is now a long string of British children’s book awards should be named after a writer whose work is largely forgotten – even by persons ‘in the trade’. (At one of the recent Eleanor Farjeon Award ceremonies, I believe that Farjeon’s literary executrix, Anne Harvey, was asked to explain to the attenders just who the good lady was.) Certainly there have been biographies, most notably by her friend, the librarian, Eileen Colwell, and her niece, Annabel Farjeon, but these tell us more about her character and the events of her long and ‘wide-hearted’ life than about how it manifested itself in the more than a hundred books that carry her name. I get the impression that investigating the bibliography is just too daunting for today’s critics who may excuse themselves the effort on the practical grounds that the children’s books of the first half of the twentieth century are of no consequence to our present enlightened times[1].

If you believe that ‘books are for keeps’ though, it is incumbent upon you to rescue each author – and especially one as prolific as Eleanor Farjeon – from generalised judgments as to their merit. Furthermore, given the growing diversity of design measures available to the makers of children’s books from as far back as the 1840s, the physical presence of an individual volume can play a part in its literary character. (We don’t need to go to the past for this – just look at a shelfful of Michael Rosen’s effusions – but editorial and production standards, including methods of illustration were far less homogenized in Farjeon’s days than now.)

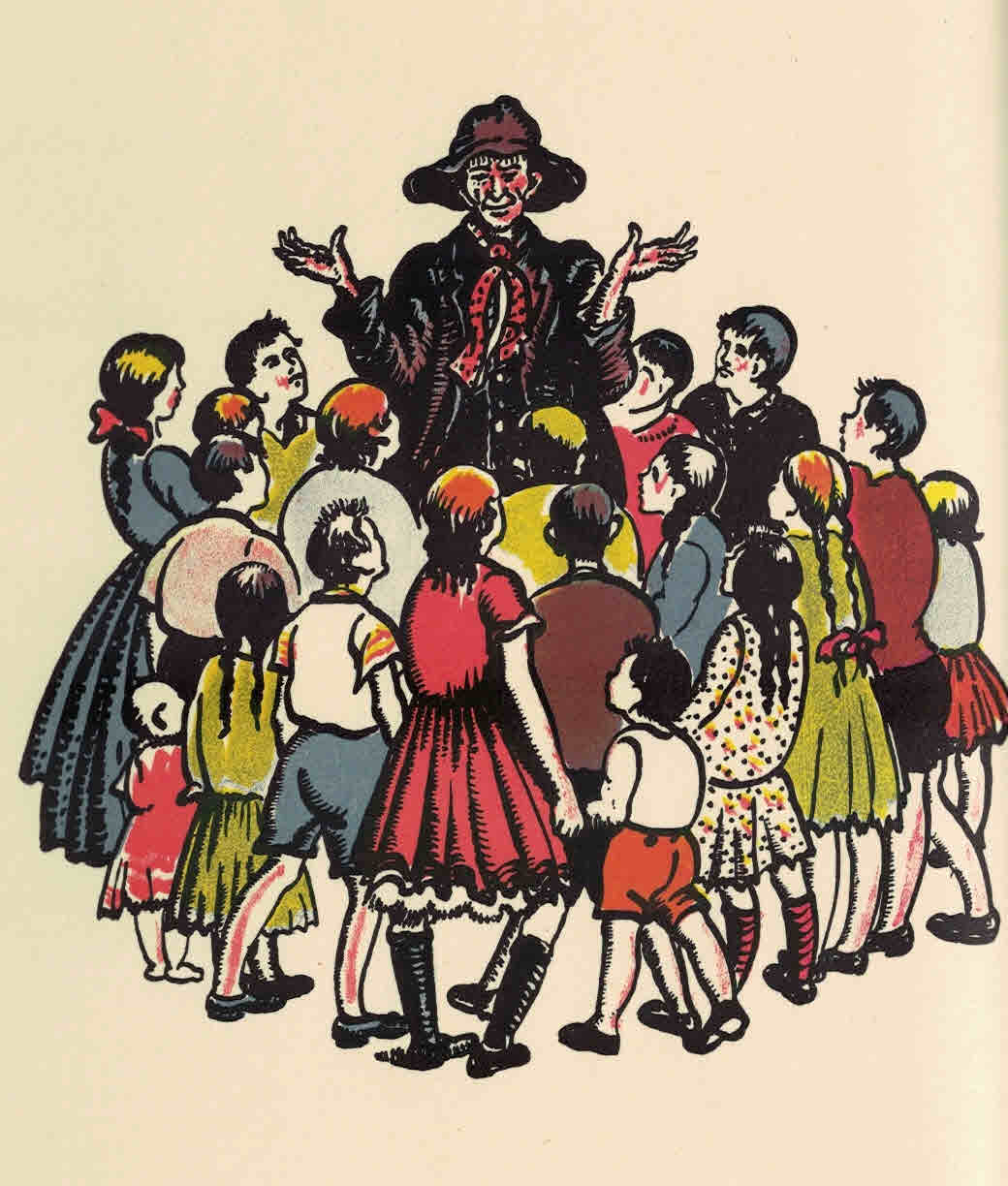

Thus it is that, looking at her verses, selections of which have been occasionally reissued down to the present, we find more than a dozen original garnerings, each with a character of its own. The first significant volumes, some of whose contents were, like those later about Christopher Robin, from Punch came as the two books of Nursery Rhymes of London Town (1916-7) with chunky line drawings for child readers by Macdonald Gill. These often punning verses contrast in their topographical knowingness with two ventures that take us back to almost Victorian party-games with a Chap-Book of Rounds, in two parts, with music by her brother Harry, and Singing Games for Children (all 1919) which exhibit the whimsy that has always bedevilled her reputation (‘self-conscious and insipid’ said Iona Opie of the singing games).

At the same time , with All the Way to Alfriston (1918), there emerged a slim volume of six poems, steeped in a Georgian pastoralism, that set a course for much of the verse that was to follow and finds echoes down to the post (second) World War poems of such as James Reeves. ‘Nursery rhymes of the Sussex Downs’ were a favoured theme of much of this writing, owing much to a faux-ballad tradition. But the writing was, as Humphrey Carpenter said, ‘deft’ and the distinctive single volumes in which it appeared , along with their illustrations, allow a discrimination to be made between treatments of themes that may be soppy or repetitive or (much-loved word) ‘retreatist’ and their origin in an immediacy of feeling.

Space forbids an analysis, but a mere listing of stages in the oeuvre indicates the varietyof impulses behind the whole. There were alphabet picture books, one of which, The Town Child’s Alphabet (1924) was illustrated by David Jones, and another, Perkin the Pedlar (1932), combined verses and invented anecdotes about places from Appledore to Zeal Monarcorum and had striking lithographs [?] by Clare Leighton. There was Joan’s Door (1926), one of the many examples of those collections that set out to imitate the Christopher Robin craze. There was the seasonal Come Christmas volume with wood engravings by Mollie McArthur (1927), whose utilitarian reprint in a larger format in 2000 shows how a reprint may suffer from re origination. In the later, more extensive assemblages that followed, such as Over the Garden Wall, with its drawings by Gwen Raverat (1933) there is a more complete establishment of the ‘Farjeon voice’, while the sequence of verse-books Cherrystones (1942), The Mulberry Bush (1945), and The Starry Floor (1949), have fluent whispy drawings by Isobel and John Morton-Sale that add a rich suggestiveness to the implications of the texts.

1925 saw the emergence of Farjeon as storyteller for children with the first tale in Blackwell’s new and intentionally ‘superior’ annual Joy Street. ‘Tom Cobble’ proved to be one of her best-known stories and may stand as an example of the wholesale use and re-use of many of the texts that followed. It was re-published by Blackwell as the first of their Jolly Books, a series (never I think examined) amounting to about seventy books, almost all being reprints in book-form of other stories from Joy Street. It also turned up as ‘Tom Cobble and Ooney’ as the first item in the daisy-chain of tales in Martin Pippin in the Daisy-Field (1937).

Grouping the tales, however disparate, within a frame, as being told by a central figure – an old nurse, say, or a sailor – was a favourite device. It allowed for second use of individual tales, either before or after the compilation, and for the preservation of texts in volume form, as, famously, with The Little Book-Room (1955), which drew upon several collections from the past. (Contrariwise, the stories for Italian Peepshow all first appeared together in the rare miscellany Nuts and May, worked on during her flight to Italy after the sadness of her miscarriage in 1925.)

These often inter-related bundles of verses and stories form a publishing continuum within which other individual successes stand out: the ever-popular verses of Kings and Queens which she wrote with her brother Herbert (1936), the 400 page New Book of Days with its fine decorations by Philip Gough (1941 – a war-time marvel), and the Anglo-American collaboration with Helen Sewell on Ten Saints (1936 and 1953). The career was certainly distinctive of its time, and, given the praise that continued after The Little Book Room won both the Carnegie Medal and the first Hans Christian Andersen Award, her many admirers among the children’s book editors must have had her much in mind when, after her death in 1965, they considered the naming of an award for a contribution to children’s literature. I wonder if the name of her near contemporary Walter de la Mare ever crossed their minds?

Brian Alderson‘s interest in children’s books began in 1954. He went on to teach Children’s Literature in London for many years and is the former children’s books editor of The Times (1967 – 1996). He founded the Children’s Books History Society in 1969 and is the current President of the Beatrix Potter Society as well as a regular contributor to Books for Keeps. Brian won the Eleanor Farjeon Award in 1969 for his outstanding contribution to children’s literature.

This article is based on an illustrated talk given at Newcastle University in 2017.

[1]An exception, confined to a now-vanished magazine, is Anne Harvey’s authoritative. 13 page survey and bibliography in Book and Magazine Collector circa 1983