This article is in the Category

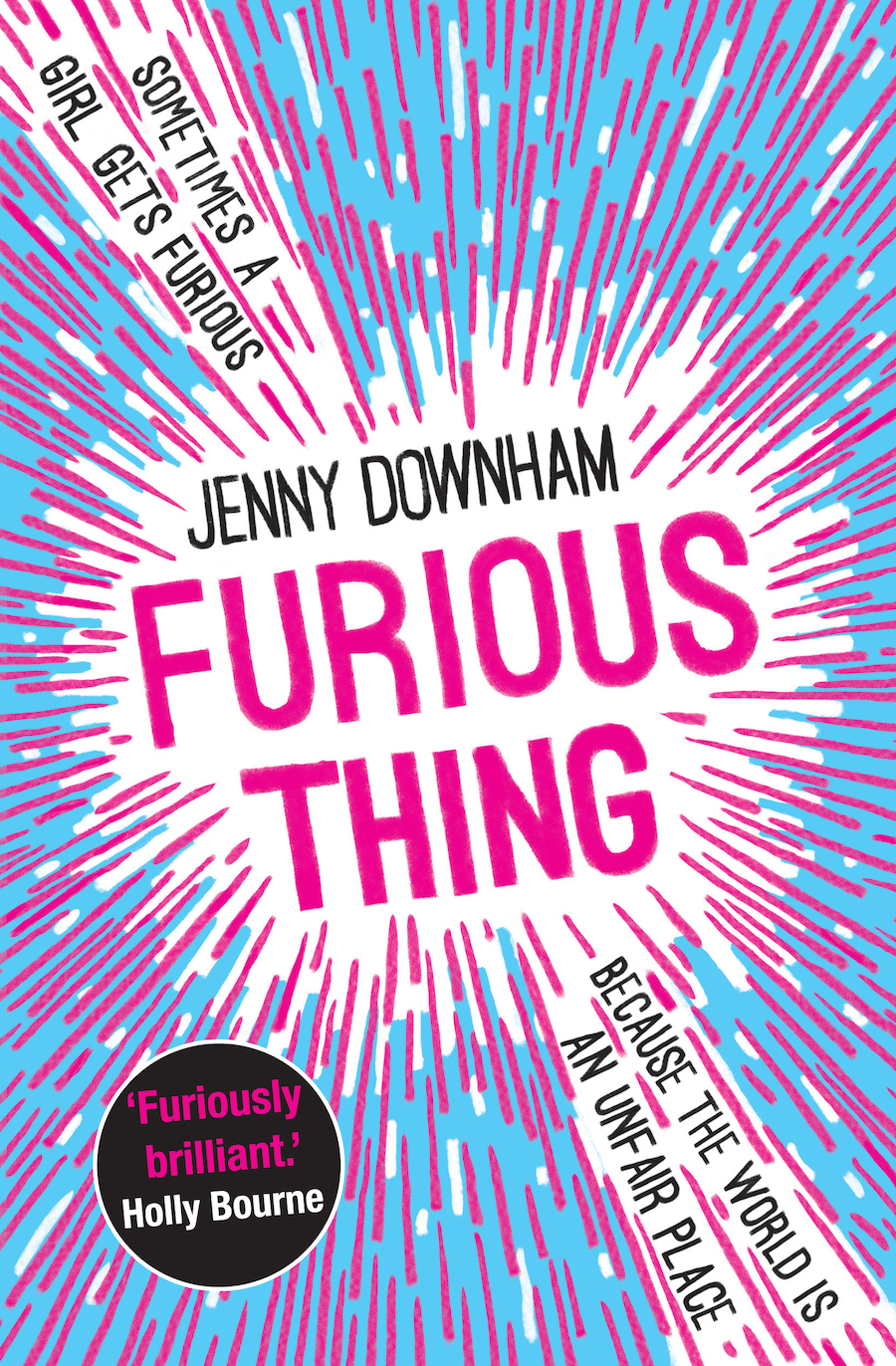

Furious Thing

Jenny Downham is one of our finest YA authors. She won the Branford Boase Award with her debut, Before I Die, and picked up more plaudits and awards for the subsequent You Against Me and Unbecoming. Her novels are often described as ‘brave’ or ‘powerful’ and Furious Thing explores a topical and troubling issue. She explains the background and her writing process.

Furious Thing took three years to write. I wish I could write quickly, but I seem unable to. I get bored if I plan, so I use free-writing techniques and that makes for slow progress. Freewriting is where you write continuously for a set period without worrying about the rules or your inner critic. So, I might open a book and put my finger on a word and write for twenty minutes. Then I might look out the window and write for another twenty minutes about the first thing I see. Do enough free writing in enough locations over enough weeks and months and a story begins to emerge. It’s a great way of working with energy and gathering lots of material. Themes, characters, location, all begin to clarify.

With Furious Thing a golden family came first – they were smart, good-looking and seemed to have everything. But among their number was someone who didn’t fit – 15yr old Lexi. Not as attractive as the rest of them, not popular or academic. Wildly rude. Always in trouble.

Her family tell her that fury is unpleasant in girls, that it’s better to be nurturing, sweet and dutiful if you want people to like you. But despite her best intentions, Lexi loses her temper over and over.

Her anger was clearly an expression of something wrong in her life. She was letting people know that her feelings mattered. But female rage is often dismissed or pathologized and instead of listening, her family chose to blame her and view her as irrational.

I realised at this point that Lexi was a scapegoat – someone who is held culpable for the things that go wrong. I was fascinated by an entire family failing to recognise this as a tactic for maintaining the image of a perfect façade and keeping their dysfunction masked. I was also fascinated by what might happen if the scapegoated child refused to accept this toxic pattern.

I had more fun writing Lexi than any other character I’ve written. She’s brave and funny and hopelessly in love and not afraid to show it. She doesn’t consider outcomes before she acts and it was enormously freeing. Her fury kept spilling and the boundaries imposed upon her kept tightening and sometimes I’d get stuck, wondering how she was ever going to get out of a particular scrape, but all I needed to do was ask, ‘So, what are you going to do about this, then?’ She’d always have something up her sleeve.

I was about a year into the project when I began to focus more on the relationship between Lexi and the person in her life who wielded the most power. She dropped things when they were around – lost her words, felt stupid, forgot stuff. She didn’t do those things on purpose. Or with anyone else. It was as if this person took away everything good in her and replaced it with fear.

And then I knew exactly the book’s direction. This was going to be a story about controlling and coercive behaviour. I knew it would be a challenge. It’s such a slippery thing to describe. We don’t really talk about it. We find it hard to see in our own lives, almost impossible to see in others’ lives and yet it’s everywhere. Someone in Lexi’s life was using abusive behaviour to dominate her. Yet she’d never heard the phrase ‘controlling and coercive’ and had no idea what was happening to her and when she did begin to see it, she didn’t have words to express it.

This type of abuse only became illegal in England and Wales in December 2015. Before that, if you’d gone to the police to report it, the perpetrator needed to have committed a violent offence such as assault to be charged. But now the law recognises that abuse that happens over time – a repeated pattern of humiliation, intimidation and threats that erodes the sense of self – is also a crime.

I was excited to write about a teenager who trusts her own instincts about what is right and wrong and who uses anger as an appropriate response to injustice. It was also a challenge to write a book that contains a lot of love, light and laughter, despite the difficult subject matter.

There are lots of girls and women in the world with real and justifiable cause to be angry. If I had one wish for this book, it would be that some of them feel heard and are able to voice their experience and find validation. Anger can be an eloquent expression of passion and a transforming force.

As Lexi tells us at the end of the book: ‘Joy exists in the world. And you deserve it.’

Furious Thing is published by David Fickling Books, 978-1788450980, £12.99 hbk.