Murder-mystery shenanigans: an interview with Beth Lincoln about The Swifts

Michelle Pauli interviews Beth Lincoln, author of The Swifts.

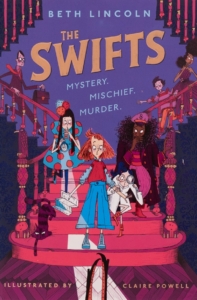

Take a classic house-based murder mystery, give it a Gothic tinge and introduce a fantastically eccentric extended family and a hunt for a long-hidden hoard of treasure. Then throw in a Scrabble duel to the death, aunts who rehearse their own funeral weekly, a boobytrapped library, endless wordplay and…no, even then you’d be barely a bubkes towards capturing the wild, comic inventiveness of The Swifts.

The New York Times bestselling, Nero award-shortlisted, Carnegie Medal-nominated middle grade debut from Beth Lincoln burst onto the children’s books scene last year with utter glee. Its original concept – a family given names at birth that are selected at random from a sacred dictionary and which they must then live up to – is compounded by a captivating central character in Shenanigan Swift who is desperate to live a life not predetermined by her name, and a gripping murder mystery plot that hurtles along, tossing bodies in its wake.

The New York Times bestselling, Nero award-shortlisted, Carnegie Medal-nominated middle grade debut from Beth Lincoln burst onto the children’s books scene last year with utter glee. Its original concept – a family given names at birth that are selected at random from a sacred dictionary and which they must then live up to – is compounded by a captivating central character in Shenanigan Swift who is desperate to live a life not predetermined by her name, and a gripping murder mystery plot that hurtles along, tossing bodies in its wake.

However, despite the urgency of the writing on the page, the novel was written in anything but a rush.

‘It’s been in my head for so long now, percolating,’ says Beth Lincoln. ‘As writers know, you’ll come up with ideas and they’ll just sort of sit there in the back of your mind growing roots or getting out of control, like mould or fungi, until they take over everything.’

It all began, some years ago, with a writing exercise that produced Shenanigan Swift – arguably one of the best named characters of any children’s book (though her Uncle Maelstrom and Arch-Aunt Schadenfreude come close seconds).

‘I’ve always been really terrible at figuring out names for people,’ Beth explains. ‘So I started doing an exercise where I’d open the dictionary at random and pick a word that I liked and then think, well, how could I make a character who would match that sort of definition? And then, how would I subvert it? For a couple of years, whenever I was bored or thinking about something else, I’d make one up. I ended up with a whole little booklet full of these random people – but it started with Shenanigan.’

The breakthrough with the wider story came when Beth allied her name game with her love-hate feelings towards Christie-esque whodunnits. While she’d always been a fan of the country house murder mystery genre, she was also frustrated by their authors’ tendency to focus on the investigation to the detriment of character and the overload of ‘really quite galling, stiff upper lip Britishness’.

As a result, Beth decided to have some fun with the genre, playing with the tropes, picking the bits she liked and putting them together in a new way and, crucially, modernising the characters. The Swifts is deliberately populated by a varied cast, created to better reflect the different identities and values of today’s young readers.

‘The genre is so often steeped in sexism, misogyny, colonialism, all of the unpleasant aspects of British culture that’s been stuck onto everything since we’ve been a country. I wanted to write something with the cosy vibe, but which was much more friendly to people like me – so, queer people. And to have that be a completely normal part of life for these characters. It’s the kind of family that I have accumulated myself, not just the people that I’m related to but the people who are close to me in my life.’

For example, there’s Shenanigan’s cousin Erf, a non-binary child who’s a dab hand at knitting their own jumpers, as well as other queer characters, but their identity is always presented simply as one facet of character rather than being a central preoccupation of the story. For Lincoln, the two strands of the tale – the metaphor about definitions and Shenanigan’s own struggle not to be defined by her name and her family’s expectations around her personality, as well as wider questions of identity – weave together neatly.

‘Erf’s journey is about being able to use their real name and not have to use their dead name anymore. That’s really relevant to a growing number of kids: how do I assert myself and my identity in the way that I feel and the way that I experience the world to a person who is an authority figure or just to other people in my life? It was nice to have that metaphor of the dictionary and dictionary definitions as something that’s so concrete and immovable and to play around with it and go, well actually language is changeable and the way that we describe ourselves and the world around us is so changeable that there isn’t such a thing as a rigid definition for anything. And that’s quite freeing.’

Another character that shines through story is the Swifts’ grand but dilapidated old house, complete with turrets, secret rooms, mazes, statues and lakes. Being brought up in an old Victorian railway station house, on a small coal route railway line between two villages near Durham, ‘that creaked and talked to you and would randomly turn off electricity and the boiler and that kind of haphazard nature’ left Beth with a fine appreciation of how buildings can shape the personalities of the people who live within them.

‘The ‘capital H House’ in The Swifts was very much born out of my love for these ridiculous old buildings that are sagging under the weight of their own history and have been added to and taken from over a long period of time,’ she explains.

Beth’s own history is filled with the joy of words and language. She describes rifling through her grandfather’s old leatherbound dictionary as a child, discovering new, unpronounceable words, and she brings that playfulness to her school visits, putting up lists of archaic words on a PowerPoint slide behind her and relishing the sight of a class of children whispering ‘snollygoster’ and ‘bumbershoot’ under their breaths to themselves, playing with the sounds.

Her love of reading and books led her to a degree in English Literature, even as an anxiety disorder stopped her from writing her own stories in her teens. She returned to it when she applied for an MA in Creative Writing at Newcastle University ‘on a whim’ and wrote the first five chapters of The Swifts as her dissertation. Shortly after, in 2017, she was one of 12 aspiring writers selected from thousands for the Penguin Random House’s WriteNow scheme, an editorial programme for new writers from underrepresented communities. A book deal with Puffin for two books followed, which was then matched this year with a six-figure two-book deal. Swifts fans can look forward to at least two more books in the series, with the next one, A Gallery of Rogues, due out later this year.

However, Beth also has ‘a million other ideas’ for stories she wants to tell, both children’s and adults.

‘Knowing that this is a career that I can build on and have longevity in is incredibly important as a person who is a bit weird. It’s the best feeling in the world. I want to still be doing this 10 years from now, 20 years from now. I want to be the tiny little shrivelled author that they have to wheel out on stage with her hundred and sixth book – that sounds great to me,’ says Lincoln, laughing.

Michelle Pauli is a freelance writer and editor specialising in books and education. She created and edited the Guardian children’s books site.

The Swifts is out now in paperback, published by Puffin 978-0241536452, £7.99.