Nursery Rhymes for Uncertain Times

Nicholas Tucker finds a nursery rhyme anthology worth celebrating.

‘Nursery rhymes call for as little of anything in the way of introduction as would Mr.Punch, Guy Fawkes or Santa Claus at a children’s party.’ So the opening lines of Walter de la Mare’s preface to the anthology Nursery Rhymes for Certain Times, published in 1946 and reprinted several times. He continued ‘Indeed there cannot be very many benighted creatures over seven, with English for their mother tongue, who haven’t at least a few of them by heart.’

He was right. Nursery rhyme anthologies took off big time with the invention of cheaper and better colour printing towards the end of the nineteenth century. Prettified by Kate Greenaway, given some muscle by Randolph Caldecott and set to their familiar music by Walter Crane in The Baby’s Opera, nursery rhymes, never under any sort of copyright, offered publishers a fine opportunity to make money and many did just that.

He was right. Nursery rhyme anthologies took off big time with the invention of cheaper and better colour printing towards the end of the nineteenth century. Prettified by Kate Greenaway, given some muscle by Randolph Caldecott and set to their familiar music by Walter Crane in The Baby’s Opera, nursery rhymes, never under any sort of copyright, offered publishers a fine opportunity to make money and many did just that.

At the same time parents and grandparents without such books but still retaining memories taken from an oral tradition carried on singing or chanting the rhymes just as they always had. Often quoted in conversation as well as in fiction and autobiography, even political cartoons made use of nursery rhymes characters, with Humpty Dumpty a particular favourite. Sometimes also appearing in pantomimes and later in many BBC programmes for children, their overall fame and popularity never seemed in question. I should know – being addressed as Tommy Tucker as a child more often than I can remember.

There were a few doubters. Animal welfare groups objected to the occasional cruelty shown to animals – ‘Would you like your tail chopped off with a carving knife?’ as the founder of TFAR, Teachers For Animal Rights, put it in 1983. But this objection, together with fears that Pussy’s in the well could lead to thoughtless imitation failed to take hold. Others took exception to the chopped off heads, babies falling out of trees and frequent beatings – children and wives.

But attempts to popularise ‘reformed’ nursery rhymes never got anywhere. The BBC eventually dropped the lines from Goosey Goosey Gander where an old man is thrown downstairs from its programme Listen with Mother, but new anthologies from modern illustrators were even more outspoken than before. Raymond Briggs’ best-selling The Puffin Book of Nursery Rhymes, published in 1966, won the Kate Greenaway Medal for that year while also bringing back a few quite brutal rhymes that some former editors had finally decided to drop.

What for years served to put these and all other nursery rhymes beyond criticism was the way that for centuries they had played such a  popular part in the nation’s common heritage. Surviving as part of an oral culture long before any of them got into print, they were handed down by children, now adult themselves, to their own children with the whole process then repeated after that. They can therefore be seen as the only children’s literature chosen by children themselves because they loved them so.

popular part in the nation’s common heritage. Surviving as part of an oral culture long before any of them got into print, they were handed down by children, now adult themselves, to their own children with the whole process then repeated after that. They can therefore be seen as the only children’s literature chosen by children themselves because they loved them so.

There were many explanations why this should have been. Dylan Thomas saw the best of them as pure poetry. Linguists pointed out that rhyme, strong rhythm and song all combined in the shortest of stories to make for easy memorising. If the story made no immediate sense, as for example in Pop goes the weasel, it was the very sound rather than the meaning of the words that appealed – why else would such a nonsensical rhyme have been remembered at all? Psychologists added that while other literature for infants usually avoided extreme violence or death, nursery rhymes thrived on such topics more often than not to the ultimate enjoyment of their young audiences.

And yet, with so much going for them nursery rhymes are now in a sorry state. No new anthology from a leading illustrator has appeared for years, and many small children no longer know if not any of them only a very few. Children’s radio and television broadcasts, once such an ally of nursery rhymes, are at low ebb and infant schools, conscious of the need for diversity, increasingly back away from a nursery rhyme culture so firmly rooted in a traditional British past. Busy parents seem to have less time or inclination to read to their children as the screen increasingly replaces the page.

There are also more critics around to pounce on reading material now seen by some as too controversial to be offered to the young. They have a point where some former anthologies are concerned; would anyone now defend a new outing for Taffy was a Welshman, Taffy was a thief or Jack selling his gold egg ‘To a rogue of a Jew’, still included in the anthology already quoted introduced by Walter de la Mare? But other critics go further, wishing to purge classic children’s literature of all traces of former negative opinions about race, sex or class prejudice. Some publishers have tried to meet this challenge by bringing out offencelessly modern versions of the rhymes, but none of these have been successful. Others, faced by the dismaying possibility of future contention, have simply walked away from nursery rhyme anthologies altogether.

There are also more critics around to pounce on reading material now seen by some as too controversial to be offered to the young. They have a point where some former anthologies are concerned; would anyone now defend a new outing for Taffy was a Welshman, Taffy was a thief or Jack selling his gold egg ‘To a rogue of a Jew’, still included in the anthology already quoted introduced by Walter de la Mare? But other critics go further, wishing to purge classic children’s literature of all traces of former negative opinions about race, sex or class prejudice. Some publishers have tried to meet this challenge by bringing out offencelessly modern versions of the rhymes, but none of these have been successful. Others, faced by the dismaying possibility of future contention, have simply walked away from nursery rhyme anthologies altogether.

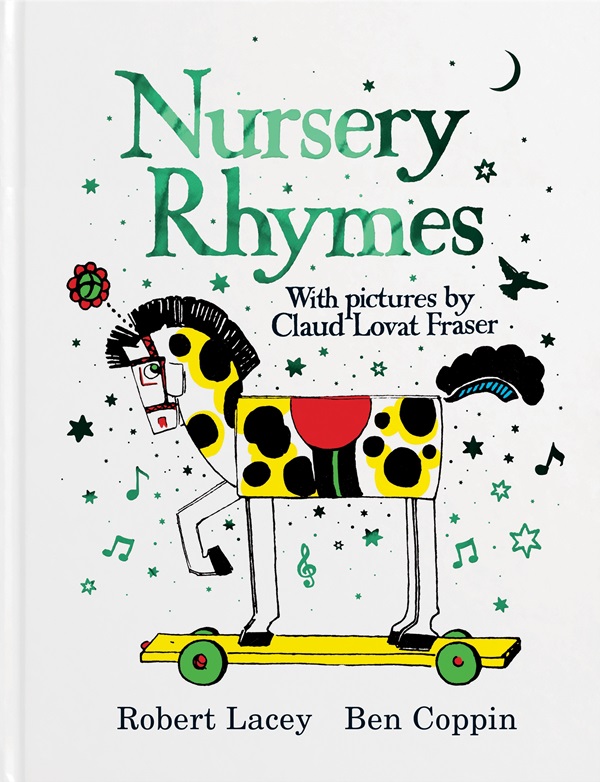

But for parents and teachers who think there is still enough unique value in these wonderful old rhymes to outweigh their occasional questionable attitudes there is now Nursery Rhymes with Pictures by Claud Lovat Fraser, edited by Robert Lacey and published this autumn by Paper Argosies, Lacey’s own publishing house. Costing £20 hardback, this is a loving re-presentation of an anthology that came out in 1919. Lovat Fraser was a fashionable stage designer, much given to using the brightest of colours. But gassed in the trenches in 1914 aged 26, his health never recovered and he died in 1921 two years after his anthology was published.

His luminous pictures, brilliantly restored by the young Deptford artist Ben Coppin, were designed for Fraser’s newly-born daughter Helen. They surely deserve to be enjoyed by new generations of infants too. Smiling nursery rhyme characters are allowed a page each, as if really happy at this re-appearance. Of all the old shockers that have caused some trouble in the past there is no trace save, perhaps, for the three blind mice still no match for a portly farmer’s wife with a gin bottle stowed in her pocket.

Robert Lacey, who has overseen this project, supplies an introduction and writes a paragraph about every rhyme’s possible meaning at the book’s end. Older children can learn a good deal of history from an author with an excellent track record for writing about the past. Hidden away there is also an intriguing mini-story about the making of the book itself. Printed and bound in the UK using 100% renewable electricity by Gomer Press of Ceredigion, West Wales, the endpapers are recycled from used paper cups and other post-consumer waste, while the cover data band is printed on thick paper board made from the fibre of brewers’ hops.

On the cover, a cheerful wooden horse about to conquer Troy (a detail taken from one of a number of lesser-known rhymes) shares a good humoured glance with his potential young readers as if inviting them to explore the pages within. I hope a good many of them will.

Nicholas Tucker is honorary senior lecturer in Cultural and Community Studies at Sussex University.

Nursery Rhymes with Pictures by Claud Lovat Fraser, introduced by Robert Lacey, Paper Argosies, 978-1738559503, £20.00 hbk.

Nursery Rhymes with Pictures by Claud Lovat Fraser, introduced by Robert Lacey, Paper Argosies, 978-1738559503, £20.00 hbk.