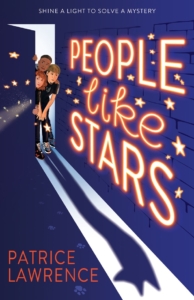

People Like Stars An Interview with Patrice Lawrence, shortlisted for the Nero Book Awards

If you’ve been following Patrice Lawrence’s work over the years, you will know that anticipating what she’ll deliver next is impossible. It is just as likely to be a film-noir-tinged YA thriller (Eight Pieces of Silva 2020) as it is to be a witty picture book empowering children to come back at adults’ nosy questions (Is that Your Mama? 2023). So, when Scholastic asked her to pause the final instalment in her fantasy series, Elemental Detectives (2022-2025), in order to focus on a contemporary middle grade mystery, Patrice made the switch. And that extraordinary mercurial talent of hers has, yet again, reaped dividends, winning her a coveted place on this year’s Nero Book Awards’ Children’s Fiction Shortlist. In the next in our series of interviews with the shortlisted authors, Fen Coles of Letterbox Library talks to Patrice about her shortlisted book, People Like Stars.

If you’ve been following Patrice Lawrence’s work over the years, you will know that anticipating what she’ll deliver next is impossible. It is just as likely to be a film-noir-tinged YA thriller (Eight Pieces of Silva 2020) as it is to be a witty picture book empowering children to come back at adults’ nosy questions (Is that Your Mama? 2023). So, when Scholastic asked her to pause the final instalment in her fantasy series, Elemental Detectives (2022-2025), in order to focus on a contemporary middle grade mystery, Patrice made the switch. And that extraordinary mercurial talent of hers has, yet again, reaped dividends, winning her a coveted place on this year’s Nero Book Awards’ Children’s Fiction Shortlist. In the next in our series of interviews with the shortlisted authors, Fen Coles of Letterbox Library talks to Patrice about her shortlisted book, People Like Stars.

Being on this year’s Nero Book Awards’ shortlist is a position Patrice feels proud of. Having been a judge for the Nero Awards the previous year, she knows the weight of discussion which curates the shortlists. She also appreciates the publicity the award affords shortlistees beyond the nominations themselves, vital oxygen in what is an ever-shrinking landscape for children’s book awards and indeed children’s book reviews altogether.

Patrice’s writing stretches with ease across genres, topics and age ranges but never at the expense of what feels authentic to her. As she says, ‘I’m not very good at writing to trends…I can only write about thing I care about.’ This extends to the great many social justice issues which she pulls in to her work, exposing the institutions and social structures which too often trip up and fail young people. Of People Like Stars, Patrice says, ‘It’s a book which I hope can promote conversations about many things, as well as being a mystery and being fun.’ Those many things include our housing crisis which has led to thousands of children ending up in insecure housing (169,050 children according to a 2025 report), a situation captured through the characters of Sen and her mum who move between hostels, temporary beds with friends and family and rent-for-wages accommodation. This portrayal was partly inspired by Patrice’s stays in a London Travlelodge where she noticed the occasional parent with a child in a school uniform, families she then learnt were without permanent homes. She explains: ‘It’s a bit like being fostered. You’re moved really quickly. It’s awful. And because it’s in hotels, it’s a hidden problem.’ She talks about the unsuitability of so much temporary accommodations for young children, the health hazards they face and the ‘hyper-adrenaline’ they must carry with them, never knowing where they’ll sleep next. With shrinking benefits and rising house prices, Patrice asks, ‘How do you manage in an economy where everything is so expensive?’

Patrice also uses Sen to expose the use of school isolation rooms for pupils deemed disruptive. We see Sen punished for not wearing a  school blazer (hers was stolen and she knows her mum can’t afford a replacement). Patrice questions the ‘logics’ of some educational regulations, wondering at their rationale and noting how these often have a disproportionately negative impact on working class and poorer children as well as young people ‘whose brains might be wired a bit differently.’ On pupil isolation specifically, her tone shifts from frustration to exasperation: ‘How dare you put young people in this situation because they don’t fit into your standard classroom behaviour. Where is the pastoral care? These are young people with so much potential and already you’re labelling them.’

school blazer (hers was stolen and she knows her mum can’t afford a replacement). Patrice questions the ‘logics’ of some educational regulations, wondering at their rationale and noting how these often have a disproportionately negative impact on working class and poorer children as well as young people ‘whose brains might be wired a bit differently.’ On pupil isolation specifically, her tone shifts from frustration to exasperation: ‘How dare you put young people in this situation because they don’t fit into your standard classroom behaviour. Where is the pastoral care? These are young people with so much potential and already you’re labelling them.’

The characters of Sen and the unconventional Vixen articulate these frustrations. In Sen, especially, we hear echoes of Indigo Donut’s (2017) and Needle’s (2022) protagonists, a whirlwind of righteous anger, cutting through institutional nonsense-speak and euphemisms, exposing the very bones of creaking social structures. ‘I just like writing angry girls’, Patrice enthuses. She is passionate about countering ‘the stigma around girls expressing anger’ and sometime wonders if she is giving vent to the anger she felt she had to swallow down as a child herself. Sen is a force who demands our attention and our concern in such a way that while Ayrton sits at the heart of People Like Stars’ mystery, it is Sen who seems to linger in and stalk the reader’s mind.

While Patrice famously floodlights her young protagonists centre stage, especially those so often overlooked in young people’s literature (as in society at large), People Like Stars stands out for foregrounding an older woman: the artist, Vixen. The book’s acknowledgments reference Patrice being ‘called out’ at a Primadonna Festival panel and reminded that older women are too often relegated to stereotypes of grandmas. As she says, ‘We put women in these boxes of expected domesticity’.

If People Likes Stars’ chapters channel the perspectives of its young protagonists – Sen, Ayrton and Stanley – Vixen is surely the novel’s fourth protagonist. Nicknamed The Forbidden Grandma by Stanley, Vixen is such a welcome addition to the children’s literature landscape which typically only changes up tropes of frail, sofa-nodding grannies with equally ageist stereotypes of madcap ‘zany’ punchline grannies. Within this context, Vixen glows: a Banksy-styled, pink-haired, punk insurrection with echoes of Vivienne Westwood. She could have stayed on the page, larger-than-life. But she is, Patrice emphasises, a recognisable, alternative grandma manifestation: ‘This is our generation actually.’ Agreed. We increasingly see these older women, walking vividly amongst us, ‘making the choice not to be invisible.’

Which is also the choice Patrice Lawrence gifts her characters every time she turns to another story, whatever the format, whatever age the intended readership. She consistently, resolutely, makes visible people who are overlooked, under or mis- represented, whether that’s young people as a group whose ‘voices aren’t heard and are devalued’, racially minoritised and working class communities, individuals who have fallen in the gaps of welfare provision or who have stumbled in to the criminal justice system, angry girls, older unorthodox women, family structures in all of their diversity of shapes and sizes. This is the social justice anthem which holds Patrice’s collection together. And, there is a striking moment near the end of People Like Stars which reads like an artistic tribute to this. Vixen invites the young protagonists to create a mosaic triptych with her, three frames mounted side by side, each one telling the stories of Sen, Aryton and Stanley, all narratives at risk of being unheard, now enshrined, immortalised and elevated. It is, Patrice says, a gesture of optimism for her readers – ‘you want to feel hopeful about human beings and people and relationships and love and kindness…particularly at the moment… And art is a way of bringing people together.’ It’s also a work of art which resonates beyond the novel, a subliminal referencing out to Patrice’s own art as it honours and esteems dispossessed voices.

Fen Coles is co-director of Letterbox Library.

People Like Stars is published by Scholastic, 978-0702315640, £7.99 pbk.