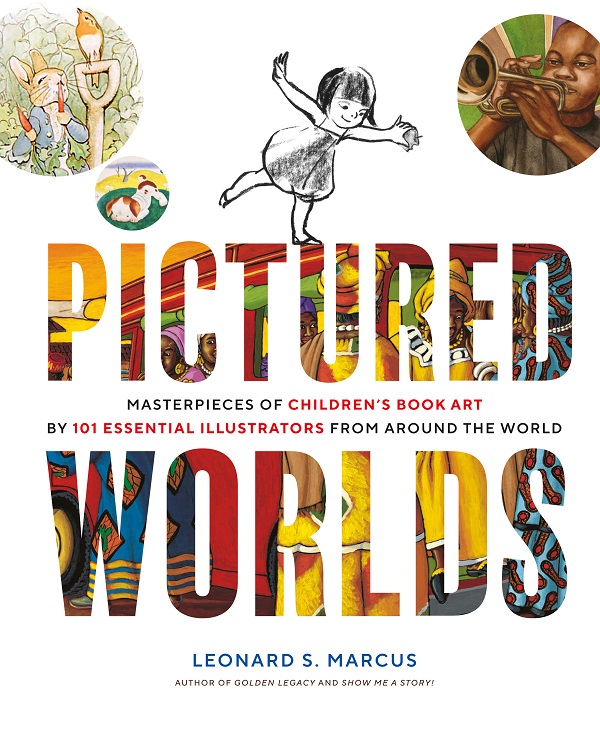

Pictured Worlds

In this extract from his new book, Pictured Worlds Masterpieces of Children’s Book Art by 101 Essential Illustrators from Around the World, Leonard Marcus chronicles the beginning of a vibrant art form and cultural driver that has touched the lives of literate peoples everywhere, and its current status.

The ideal children’s book, John Locke observed, is ‘easy, pleasant . . . and suited to [the child’s] Capacity.’ Published in London in 1693, Locke’s revolutionary advice book was called Some Thoughts Concerning Education and had something to say about all aspects of a child’s upbringing, starting with the body and ending with the mind. A child psychologist before his time, Locke speculated on the types of books best suited to young people’s capabilities and interests. In doing so, he laid the groundwork for modern-day children’s literature. Noting, for example, that a child who feels scolded or lectured to is less apt to pay attention than one for whom learning is cast as a game, he argued that a good children’s book is one in which ‘the Entertainment that [the child] finds might draw him on, and reward his Pains in Reading.’ Locke listed brevity and the addition of illustrations as two other key elements of effective bookmaking for the young. Pictures, he said, were an essential ingredient because, from the child’s perspective, showing always works better than telling.

Widely popular in the West, Locke’s treatise inspired entrepreneurial bookmen like London’s John Newbery—affectionately dubbed ‘Jack Whirler’ by literary lion Samuel Johnson—to specialize in publishing juveniles in the mold of his forward-looking ideas. In doing so, Newbery established the first commercial market for children’s books in the West. Newbery’s small, trim paperbacks sold briskly to the burgeoning ranks of upwardly striving middle-class English parents and were soon being imitated, or simply pirated, in North America. Half a world away, in the vibrant commercial city of Edo, Japan, a comparable retail trade in akahon, or ‘red-bound’ picture books for young readers, had sprung up independently of developments in Britain but for much the same reasons. A clear pattern thus emerged that would repeat itself elsewhere around the globe many times over: the recognition of a critical link between literacy and economic and social advancement, and of the illustrated children’s book as a gateway to literacy and a better life. An occasional illustrated book for young readers had appeared in the West before Locke, most notably Johann Amos Comenius’s Orbis Sensualium Pictus (1658), a picture encyclopaedia and language primer that remained in print in one form or another well into the nineteenth century. But it was Locke’s prestigious endorsement that crystallized educated opinion and established the modern children’s book’s norms. By the time Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’s first readers were asked to consider, ‘What is the use of a book without pictures or conversations?,’ the answer was plain, Locke’s prescient ‘thoughts’ having long since taken their place as literary guideposts for the new literature for young people.

Widely popular in the West, Locke’s treatise inspired entrepreneurial bookmen like London’s John Newbery—affectionately dubbed ‘Jack Whirler’ by literary lion Samuel Johnson—to specialize in publishing juveniles in the mold of his forward-looking ideas. In doing so, Newbery established the first commercial market for children’s books in the West. Newbery’s small, trim paperbacks sold briskly to the burgeoning ranks of upwardly striving middle-class English parents and were soon being imitated, or simply pirated, in North America. Half a world away, in the vibrant commercial city of Edo, Japan, a comparable retail trade in akahon, or ‘red-bound’ picture books for young readers, had sprung up independently of developments in Britain but for much the same reasons. A clear pattern thus emerged that would repeat itself elsewhere around the globe many times over: the recognition of a critical link between literacy and economic and social advancement, and of the illustrated children’s book as a gateway to literacy and a better life. An occasional illustrated book for young readers had appeared in the West before Locke, most notably Johann Amos Comenius’s Orbis Sensualium Pictus (1658), a picture encyclopaedia and language primer that remained in print in one form or another well into the nineteenth century. But it was Locke’s prestigious endorsement that crystallized educated opinion and established the modern children’s book’s norms. By the time Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’s first readers were asked to consider, ‘What is the use of a book without pictures or conversations?,’ the answer was plain, Locke’s prescient ‘thoughts’ having long since taken their place as literary guideposts for the new literature for young people.

What do we see now? Picture books in the 21st century

The digital revolution of the early 2000s presented illustrators with a new set of tools with which to paint and draw and spawned a new art form: the app, which combined aspects of animation and the illustrated book. The internet also allowed illustrators to showcase their work to a global market, a once unimaginable opportunity that, in combination with the ease of electronically transmitting digital art to any locale, resulted in a sharp rise in the number of picture books created by collaborators working across national borders and at great distances from one another. The new technologies, however, did not, as some had confidently predicted, render the traditionally printed picture book obsolete, but seemed rather to do just the opposite. For many in the children’s book world, the ubiquity of digital imagery in everyday life highlighted the unique experiential value of the well-designed picture book that one could hold in hand as the centrepiece of an intimate encounter between an engaged caregiver and a child. By 2015, the never-very-robust demand for electronic picture books all but evaporated in the United States, and publishers found themselves redoubling their efforts to fashion picture books that were alluring material objects. All this was happening as a generation of seasoned editorial illustrators, having seen demand for their work dwindle in the shrinking newspaper and magazine market, migrated to children’s book illustration as a viable alternative outlet for their creativity. Synchronously, the audience for picture books and illustrated narratives generally was becoming more fluid as experimental zine and web-based comics artists, long accustomed to operating on the non-commercial fringe, suddenly found themselves embraced by mainstream publishers eager to build the graphic novel into a cross-generational phenomenon. Some of these artists went on to discover the picture book as well, bringing formal comics elements and, often, a hipster maverick sensibility to the genre that further enriched its narrative vocabulary. By the turn of the new millennium, the audience for picture books had expanded to include a growing number of adult collectors, aficionados, and fans. The Chihiro Art Museum, the world’s first museum of picture book art, had opened in Tokyo in 1977, initially as a local memorial to a beloved Japanese illustrator. Not only did that pioneering museum undergo a dramatic expansion in its size and mission in subsequent years, but it also set the model for an international trend. Children’s book art museums would later be established in the United States, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Finland, Germany, and South Korea, among other countries, and university archives of children’s book art and manuscripts would likewise proliferate alongside the academic study of the field. In the United States, the second decade of the new century also became the time for a long-overdue reckoning with regard to the publishing industry’s historic marginalization of children’s books by and about people of colour, a bias also embedded in publishers’ traditional hiring patterns. It was not that no effort of this kind had been made in the past, but rather that from the 1920 launch of the short-lived, NAACP sponsored Brownies’ Book magazine for the ‘children of the sun’ onward, attempts at diversifying the literature and the professional community surrounding it had been sporadic at best and had typically received only very modest support from the white mainstream of librarians, educators, and individual book purchasers. In the picture book realm, milestone events charted the course of a slow but ultimately meaningful industry-wide cultural transformation: the awarding of the 1963 Caldecott Medal to Ezra Jack Keats’s The Snowy Day (1962); the rise to prominence during the mid-to-late 1900s of African American author-illustrators such as John Steptoe, Tom Feelings, Ashley Bryan, Donald Crews, Jerry Pinkney, and Pat Cummings; the subsequent arrival on the scene of an impressive and much larger group of authors, artists, librarians, and publishing staffers representing not only the African American community but also those of Latinx peoples, Asian Americans, the LGBTQ+ population, and American Indians. As the audience for picture books steadily expands and their cultural status continues to rise, the genre appears likely to flourish well into the twenty-first century, even as other categories of printed books – reference works and disposable series fiction among others – vanish into the digital ether. To many parents and grandparents who grew up on Goodnight Moon and The Tale of Peter Rabbit, it is still unimaginable to pass down a ‘classic’ to the next generation in anything but tangible form. Yet in the end nostalgia will have had surprisingly little to do with the picture book’s long-term prospects, at least when weighed against the genre’s proven utility to engage young children in the kind of artful blend of instruction and delight that John Locke recommended long ago, and which continues to prove its worth to an ever-larger portion of the world’s population.

Leonard S. Marcus is one of the world’s leading authorities on children’s books and the people who create them. His award-winning books include Golden Legacy: The Story of Golden Books, Margaret Wise Brown: Awakened by the Moon, and Show Me a Story!: Why Picture Books Matter. A frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review and commentator on radio and television, Marcus is a founding trustee of the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art. He teaches at the School of Visual Arts and lectures about his work across the world.

Pictured Worlds: Masterpieces of Children’s Book Art by 101 Essential Illustrators from Around the World by Leonard Marcus (Abrams, £55).