This article is in the Category

Review feature: The Book of Dust

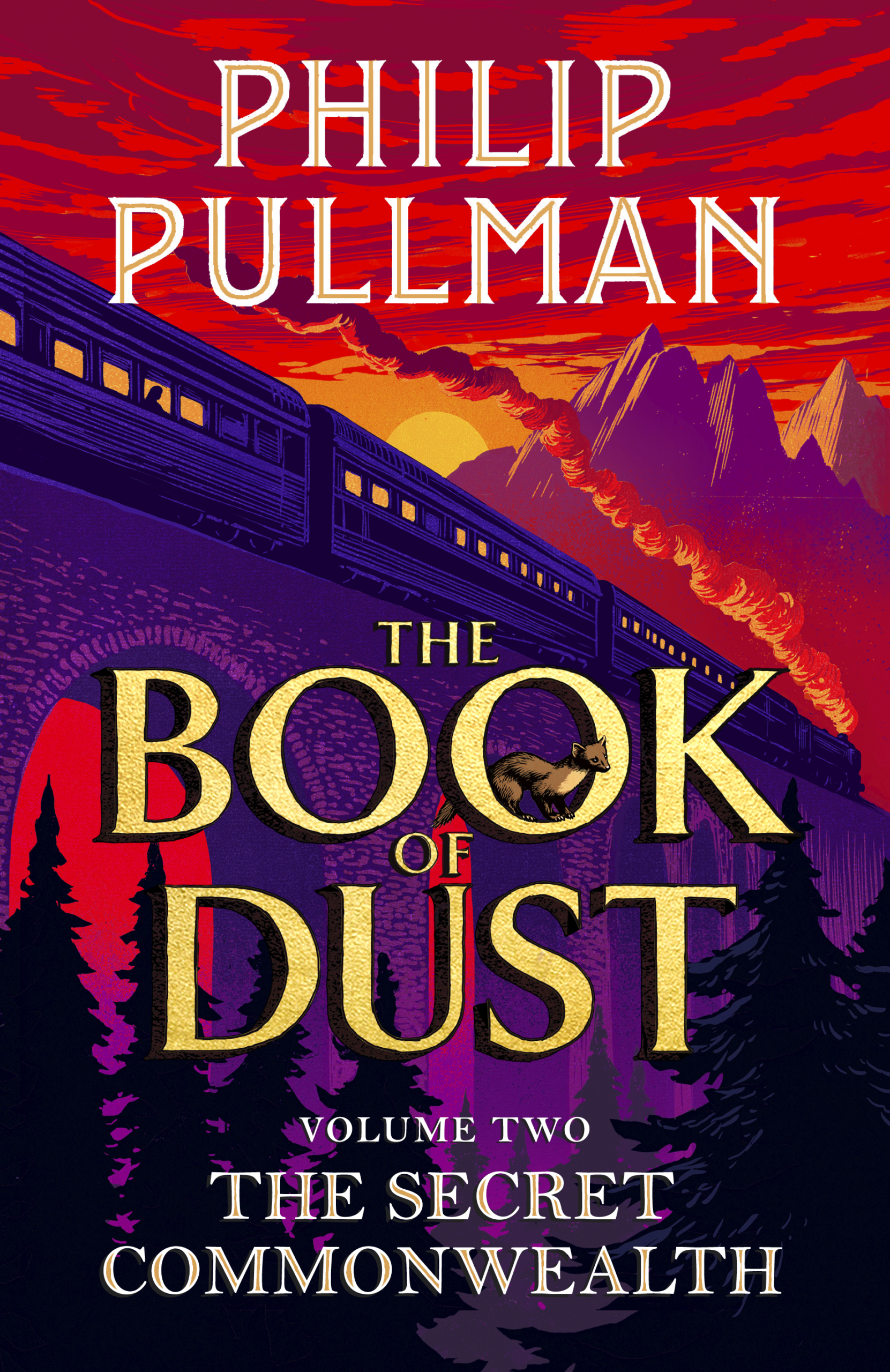

Nicholas Tucker enters The Secret Commonwealth, the second volume in The Book of Dust by Philip Pullman.

So here it is – all 687 pages of the eagerly anticipated next step in Philip Pullman’s second trilogy. Rather than following on from La Belle Sauvage, the first book in the new sequence, it jumps twenty years forwards. Lyra, the young heroine of His Dark Materials, is now aged 21. She and Will, her unattainable love from a different universe, had promised each other to throw themselves hereafter into living their individual lives to the full. This she now does as a university student, but her enthusiasm for rational argument as the only way towards discovering the truth is not working out. She has an increasingly fractious relationship with her daemon Pantalaimon, the animal spirit who is her intimate other half. He has never got over Lyra’s previous act of cutting him away in order to save a life. In Pullman’s world, this is the equivalent of rejecting one’s very soul, an experience so painful it can never be entirely forgiven.

But Pan also hates the way Lyra now ignores imagination and feeling as other ways of coming to an eventual understanding. So one day he takes advantage of his newly separate status to quit her altogether. His absence from Lyra when everyone else still possesses their own highly visible personal daemon makes her the target of suspicion and hatred. Her subsequent efforts to find him take up the rest of the narrative. Plenty of excitements and near–misses ensue, each described so convincingly it is almost to be there oneself. Even so, this extended search ultimately lacks the urgency of Lyra’s exploits in His Dark Materials. As a virtually re-incarnated Eve she once helped save the whole world from tyranny. The grandeur of this achievement is missing in favour of her more personal objective this time round.

Pullman is now looking increasingly to William Blake, in particular his conviction that ‘Everything possible to be believ’d is an image of truth.’ Or as a character in the book puts it, ‘Nothing is only itself.’ There is less discussion here of the vital existence and huge significance of Dust, so integral to all the books so far. But Lyra has one vision incorporating it when looking down from her window at a contented village scene below. Everyone she saw for that moment seemed sustained and enriched by a certain quality of spirit that gave her the ‘quiet conviction, underlying every circumstance, that all was well and that the world was her true home, as if there were great secret powers that would see her safe.’ Just as Milton is the key to the first trilogy, Blake rules in this story, subject as he was to similarly mystical visions of his own.

The rationalists in this story who turn out to be false friends to Lyra cannot really compare with her old theocratic enemy the Magisterium, set in Geneva and still aiming for thought control and world domination. Its crusading zeal and contempt for any other beliefs brings to mind Islamic fundamentalism as well as narrow historical Calvinism at its worst. But while they are still a mortal and ruthless threat this only comes really apparent in a vicious plot twist just before the end.

A sprinkling of four-letter swearing and a graphic near gang rape pushes this story well into the Young Adult bracket. Its blend of magical realism coupled with references to current events also has plenty for older readers too. Boat People appear plus new villains drawn from international capitalism. There is though an absence of those former outsize fun characters once coming to Lyra’s aid just when she needed them or else standing as formidable obstacles in their own right. Instead this story concentrates almost entirely upon her state of mind, and it is not a happy one. She ends up in pain, alone and nowhere near ending her quest. She may indeed now be wiser but sadder as well.

The title refers to what one character describes as ‘The world of hidden things and hidden relationships.’ For Lyra, it includes `Ghosts, fairies, gods and goddesses, nymphs, night-ghasts, devils, jacky lanterns and other such entities …inaccessible to science and baffling to reason.’ Pullman incorporates such things into his own fiction with all his usual brilliance. But it seems unfair to penalise Lyra for avoiding that particular route when engaged on academic research. Pullman writes elsewhere ‘She had exalted reason over every other faculty. The result had been – was now – the deepest unhappiness she had ever felt.’ Does reason as a goal always have to have such dire personal consequences?

My recent book Darkness Visible; Philip Pullman and His Dark Materials ends with an interview he and I had at his home outside Oxford. In it he describes how ‘I once put this to Richard Dawkins: if you had a little girl who was terribly ill and knew she was soon going to die, do you tell her the stark facts of her oncoming death? Of course you don’t! You tell her a fairy tale about going to heaven. What else can you possibly do?’ Dawkins disagreed at the time, but Pullman follows up this line of argument throughout this present novel. Rationalism, he insists, may indeed not always be enough, but he also acknowledges that turning against rationalism has its dangers too. It will be fascinating to see how if at all he resolves this conundrum in the final instalment of this epic work.

He is occasionally encumbered in this present novel by having to slip in too many explanations at the appearance of formerly well-loved characters that new readers will know nothing about. Otherwise he remains a master of memorable detail, expert in creating atmosphere while raising important questions at the same time. The world Lyra inhabits, as before, is the same intriguing mixture of the recognisable and the strange. This allows her author to enjoy exercising his ever-fertile imagination without necessarily reaching out to any higher purpose. But it is its underlying moral seriousness that gives this book its particular distinction. Writing of this depth and quality does not always find a ready audience. Pullman as before proves that it can and does.

The Book of Dust Volume 2, The Secret Commonwealth, Philip Pullman, 978-0241373330, David Fickling Books, £20.00 hbk