Saved by stories: an interview with 2022 Carnegie Medal winner Katya Balen

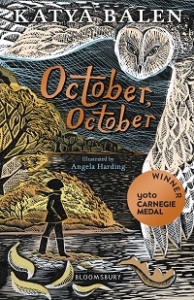

Katya Balen has just been named winner of the 2022 Yoto Carnegie Medal for her book October, October (Bloomsbury), illustrated by Angela Harding. Balen’s October, October has done the double too and scooped this year’s Shadowers’ Choice Award for the Yoto Carnegie Medal, after tens of thousands of young people across the UK and internationally read and debated the shortlisted books before voting for their favourites.

Joy Court interviewed Katya for Books for Keeps.

A ‘slightly surreal’ experience is how the Yoto Carnegie Medal winner, Katya Balen describes being told she had won both the coveted Medal and the accolade of also being the Shadowers’ Choice winner. She was in rural France with her mother and father when she received the news. It was boiling hot, and the reception was terrible, but as she was receiving the ‘best news of her life’ she had to step over the tiny corpse of a dead baby bird on the patio, which felt like a portent of doom and yet strangely appropriate for her book. Falling from a tree and a bird are indeed both significant features of October, October, which astonishingly is only Katya’s second novel.

A ‘slightly surreal’ experience is how the Yoto Carnegie Medal winner, Katya Balen describes being told she had won both the coveted Medal and the accolade of also being the Shadowers’ Choice winner. She was in rural France with her mother and father when she received the news. It was boiling hot, and the reception was terrible, but as she was receiving the ‘best news of her life’ she had to step over the tiny corpse of a dead baby bird on the patio, which felt like a portent of doom and yet strangely appropriate for her book. Falling from a tree and a bird are indeed both significant features of October, October, which astonishingly is only Katya’s second novel.

Her winning book is the story of October, named for the month of her birth, who lives an almost entirely self-sufficient and perfectly happy life in the woods with her father. A life enhanced by her stubborn rescue and hand rearing of a baby owl, her first friend, whom she has named Stig. But on her eleventh birthday everything changes when her dad falls from the highest tree, breaking his back, and she is forced to accompany ‘the woman who is my mother’ to her home in the city. Stig comes too, but heartbreakingly must be taken to a sanctuary while October has to confront grey urban life, school and other people as well as her relationship with her other parent.

I wondered where the inspiration for this extraordinary story came from and it happens that Katya has direct experience of this wild, off grid way of living. About 10 years ago her father-in-law bought 40 acres of woodland and built his own house there, growing his own food and making his own electricity and she had this ‘classic author moment’ of wondering what it would be like for child to grow up in a place like this and how they would be equipped to meet the world. The family story of how her father-in-law found, and kept, a dead owl is also relevant. She knew that an owl had to be part of her story and that the circle of life and what it means to be wild would be central.

She admitted to feeling sorry for Bloomsbury when she pitched these vague ideas for a book but she is adamant that she is not a planner and that the books reveal themselves as she writes. She describes waking ‘in a cold sweat’ sometimes, wondering what she would write the next day. Writing is a ‘tortuous process’ but she is very disciplined, writing 1000 words a day and by taking time over crafting those words her first drafts are relatively clean by they time they reach her editor.

She had always wanted to be a writer and specifically a writer for children, but she became embarrassed by this ‘self-indulgent’ ambition. She studied English at university, completed an MA researching the impact of stories on autistic children’s behaviour and became interested in Child Psychology. She ‘flitted’ around jobs in special schools, hospices and social care. But finding herself out of work at the same time as relocating with her partner she told herself to be brave because ‘If I don’t sit down and have a go now, when am I ever going to get this block of time to indulge?’ The result was The Space We’re In, her acclaimed debut, longlisted for the Carnegie and Highly Commended for the Branford Boase Award, which tells the story of 10-year-old Frank and how he and his five-year-old autistic brother Max cope with a family tragedy.

studied English at university, completed an MA researching the impact of stories on autistic children’s behaviour and became interested in Child Psychology. She ‘flitted’ around jobs in special schools, hospices and social care. But finding herself out of work at the same time as relocating with her partner she told herself to be brave because ‘If I don’t sit down and have a go now, when am I ever going to get this block of time to indulge?’ The result was The Space We’re In, her acclaimed debut, longlisted for the Carnegie and Highly Commended for the Branford Boase Award, which tells the story of 10-year-old Frank and how he and his five-year-old autistic brother Max cope with a family tragedy.

There can be no doubt that her master’s research and working experience has had an impact upon the themes she writes about. She is also co-director of Mainspring Arts, a not-for-profit organisation set up to increase the participation in the arts for neurodivergent people. She is frequently asked if October is a character on the spectrum, but she is adamant that she would not feel it appropriate to write first person from a neurodivergent perspective. She acknowledges that there are ‘obvious crossover traits’ in October’s behaviour, but she has been isolated from normal experiences and the sensory overload she experiences, for example on the Tube or in a crowded playground would be simply overwhelming. What is truly extraordinary is the way in which Katya is able to get the reader inside October’s head so that they feel every emotion, concern and anxiety alongside her. As she says ‘Words can do so many different things to different people and create all these really intense emotions’

Shadowers and adult reviewers alike have commented upon her beautiful use of language, with young people most surprised by her lack of the punctuation that they are told is compulsory. But the enthusiasm with which they race through the story and the emotional impact it has upon them is testament to her skill. Having read that she listened to audio stories at bedtime from the age of three I do wonder if that aided the development of a style which captures the rhythms and cadences of normal speech so well. She also confessed to a childhood habit of narrating aloud her own life in the third person. This stream-of-consciousness describing of everything has undoubtedly contributed to her ability to vividly evoke both settings and the internal life of her characters

Her MA also points to another very important theme – the importance of the stories we tell ourselves and each other. ‘Stories give you a greater connection to other people. Either you understand them more or you have all shared the same story and you connect on that level. We are all part of each other’s stories.’ Stories are essential to October and it is often the objects that she finds that inspire the stories in her head. This is based very much upon Katya’s own recollections of childhood collecting. ‘Children are like magpies; they take all this stuff and incorporate it into their games… The excitement of finding a piece of green glass that you can say is The Philosopher’s Stone…’ It is only when her mother introduces her to the possibility of mudlarking, searching for objects on the shore of the Thames, that October is able to reconnect with nature, to find herself and to start to create a more hopeful story for them all.

With her third book The Light in Everything just published to rave reviews and the fourth, so far untitled, with her editor, I am sure I am not the only very happy reader! Every book so far has been very different but they are all beautifully crafted, beautifully published (Bloomsbury is to be applauded for matching all her texts with phenomenal illustrators as with Angela Harding in October, October) and with unmistakeably authentic children’s voices. I strongly suspect that this will not be the only Carnegie medal for the extraordinarily talented Katya Balen.

Joy Court is a trustee of The United Kingdom Literacy Association (UKLA), co-founder of All Around Reading and Conference Manager for CILIP Youth Libraries Group. She is a Past Chair of the CILIP Carnegie and Kate Greenaway Medals.

October, October by Katya Balen, illustrated by Angela Harding, is published by Bloomsbury, 978-1526601933, £7.99 pbk.