Springboard Stories

If you’ve got a teenager in your home – or worse, thirty teenagers in your RSHE classroom – you know how hard it can be getting young people to open up about ‘difficult’ subjects. It can be ‘incredibly awkward’ or even ‘nigh-on impossible’. Cue eyeball-rolling and staring out into space. Tia Fisher has a suggestion.

Why not start with a story as a springboard? Stories are entertaining, fun and memorable. Get your audience hooked with a bit of drama and watch how they stay actively engaged.

Why not start with a story as a springboard? Stories are entertaining, fun and memorable. Get your audience hooked with a bit of drama and watch how they stay actively engaged.

After all, we don’t just learn through story – stories also open our imaginations and help us remember things better. This is because our brains are wired to remember facts when they are presented as a narrative. Stories also, perhaps more importantly, make us feel. For example, do you remember where you were when you heard about something big or significant? Perhaps a disaster, a loved one passing away, or even a job offer? Chances are, you do. That’s because when a sensation or emotion is connected to an event, we store the memory for future use. When we’re injured, our brains store information about how we were hurt so that we avoid the same mistake in the future. Experiments prove this kind of learning happens quickly, and that the resultant memory can last a lifetime. We feel – we learn – we understand.

A book might be packed with RHSE learning objectives, but if they’re integrated naturally within a story, they won’t feel like a lesson, and the emotional impact will make them stick. Stories also offer distance: a safe space for young people to explore sensitive topics and discuss difficult issues, without feeling directly targeted or put in an uncomfortable position – kind of like ‘asking for a friend’.

A book might be packed with RHSE learning objectives, but if they’re integrated naturally within a story, they won’t feel like a lesson, and the emotional impact will make them stick. Stories also offer distance: a safe space for young people to explore sensitive topics and discuss difficult issues, without feeling directly targeted or put in an uncomfortable position – kind of like ‘asking for a friend’.

Choose a protagonist and a predicament carefully so your audience feels recognised, understood and included. The difference in engagement when a story is truly relatable is that it leaves an imprint, a trace. Fiction is nuanced, with a well-paced, exciting story with believable characters that readers truly care about. These characters will not only capture interest, but also add context and complexity. There is time and space within a story to build the layers and contradictions which will add credibility and reflect life as it actually is, muddled and conflicting.

A story can often offer a heap of different perspectives on the same problem. Empathy – our ability to imagine and share someone else’s feelings and point of view – boosts learning and creates a larger level of tolerance. So, how cool is it that empathy is a learned skill, and reading is the best workout to build those empathy muscles? Through a book, you literally step into the world and thoughts of another person to understand them better, seeing the world through their eyes.

By presenting new ideas within a narrative, stories challenge perceptions and spark conversations that can change minds. Adolescence is a crucial time when young people are calibrating their moral and political compasses. If you’re in a classroom or a reading group, many ‘issue-based’ books come with free discussion and learning resources to help you support them in that process.

Writers who tackle challenging topics carry massive responsibility towards their readers to be both accurate and informative. This often includes sensitivity and accuracy readings, as well as helpful resources. When I was writing about county lines, I knew a neat happy ending would be inauthentic, but it was important to end on a hopeful note. This is why my protagonist reaches out for the kind of support I signposted at the back of the book.

The vicarious experience of standing alongside a character as they face their problems inspires us to think about what we might do in similar situations, and what the possible consequences could result. Reading is like a rehearsal. Have you ever felt your heart racing at a scary moment while reading or listening to a story? It is an astonishingly complex activity: PET scans reveal that the brain actually lights up as though what we’re reading about were happening in real life. Most teens crave danger; perhaps stories present life’s thrills and spills with a safety net.

We know that reading for pleasure is at an all-time low and our attention spans are shortened by social media. So, remember that stories come in different, equally-valid, formats. Audio or graphic novels count as well. And of course, I have to give a special mention to narrative verse! It’s a pathway into reading for so many young people who feel overwhelmed by what Jason Reynolds dubbed the ‘big black blocks of text’ in conventional prose. Narrative verse is like a concentrate: all the emotion, intensity and immediacy, in far fewer words.

Education disguised as entertainment. What’s not to love?

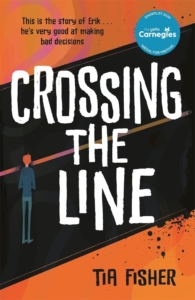

Tia Fisher writes books from middle grade to YA in both prose and verse, and delivers realistic fiction for young people on important topics that spark big conversations. Books include Not Going to Plan (Hot Key Books, August 2025) and her Tia’s debut verse novel about county lines, Crossing the Line (Hot Key Books, 2023) won the prestigious Carnegie Shadowers’ Choice Medal, and the UK Literacy Association Award.