Telling stories through non-fiction

Award-winning author illustrator Kate Winter describes how picture books can connect readers to the past.

I have always been interested in non-fiction and history. As I child I was taken to archaeological digs and ancient sites, and to beaches to search for fossils. My father was fascinated by history and prehistory and imparted his knowledge and enthusiasm to us, while my mother and her mother were story-tellers and performers, inviting us to imagine and dream and inhabit lives. As a young adult I discovered documentaries and experimented in film making, spending much of my time at university interviewing people and trying to piece together stories that summed up a time and a sense of place.

I studied sculpture at the Slade School of Art and made sculptures dedicated to characters from my past and family history. It’s always been fascinating to me that whatever art form I find myself working in, I always come back to non-fiction and real-life stories. It makes so much sense that the stories I write for children have the same focus on time and history.

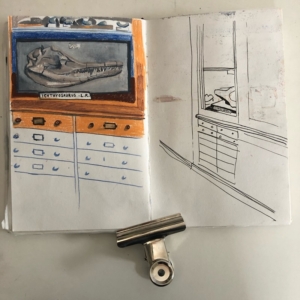

I explore my characters through writing and drawing. Drawing plays a key role for me in connecting to the past. I find that through drawing I can connect to the story better, just as a method actor would embody their character through movement or a writer might muse on the intentions that drive their protagonist. Drawing becomes a vital part of understanding an idea and gaining knowledge and a familiarity; a practical epistemology or ‘active learning.’

When I research the ideas for the book I like to experience as much first hand as I can. It helps me to feel connected to the past by spending time in the actual location where history took place- for my book The Fossil Hunter, about Mary Anning, I was able to visit Lyme Regis where she lived all her life and found many of her fossils. I was fortunate to be able to visit museums; The Lyme Regis Museum, The Sedgwick Museum of Natural Sciences in Cambridge and The Natural History Museum in London; all enabling me to see the fossil specimens she discovered. I was able to read up on the time and theories in wonderful books by great historians and writers such as Tom Sharp, Patricia Pierce and Tracy Chevalier and to read many of Mary’s own letters and writings.

The Cave Explorer, my latest book, is about the Lascaux Cave but at its heart it’s about the importance of stories and creativity. You are no longer allowed to visit the real cave, but replicas are made authentic by dimmed lighting, soundscapes and candle-lit tours allowing visitors to imagine the experience of the real thing. I painted my version of the cave paintings on my own walls to try to feel the technique and movement of the artists. And I created many of the illustrations in the second half of the book using the same pigments and methods that our prehistoric ancestors would have used. By doing these things I feel better positioned to impart a sense of authenticity to my readers.

I find that if I can locate the main themes of the story then the illustrations will start to emerge on the page without a text prompt or need of a wordy explanation.

In The Cave Explorer I show Marcel on the left side of the page looking at a wave of prehistoric paintings, while the right side shows a prehistoric human painting the images. While the two characters on the page exist in different eras, I hope readers get the sense of the past and present being connected, as we are to our ancestors.

As writers and illustrators, we have the immense privilege of being able to connect with children not only through words and descriptions but also through the universal language of images. An image can tell a thousand words, and one child might notice or interpret something in a totally different way to another, based on their life experience or connection to the themes in the story. Even without text, images alone can take the reader on a journey.

Growing up with books like Eric Carle’s The Very Hungry Caterpillar with its wonderful array of delicious food, so real it felt like I could reach out and grab it, were immensely exciting to me. Looking behind paper doors or flaps or opening up a letter in the Ahlberg’s The Jolly Postman was like finding treasures and encouraged a deeper and intimate connection to the story, by inviting the reader to be a part of it. I am still very interested in exploring and experimenting with the interactivity of books and the space around the book.

In both The Fossil Hunter and The Cave Explorer gatefolds make a super wide panoramic pull out, intended to create the sensation of opening up the past and revealing the prehistoric landscape. I hope the moment a child opens the gatefold they will feel a sense of wonder and an experience stepping back in time. Afterall wonder is the first of all passions, said Descartes. I also hope they feel that they are stepping into the protagonist’s imaginations. I have tried to deliver what I hope will be an awe-inspiring journey to a prehistoric world and into the minds of the main characters who lead each storyline. I want history to come alive for my young readers.

The whole book format excites me as a connective space and a starting point for conversations about history, the world and human existence. I hope that the playful peritextual devices I use invite the reader to feel a deeper connection to the story and to get a sense of time-travel through history. I believe strongly in the importance of the picture book and how visual communication is an inclusive and powerful tool to connect with people of all ages. I hope the world continues to value the storytellers and artists and that books continue to create starting points for new perspectives and ways of thinking.

The Cave Explorer is published by Puffin, 978-0241469927, £14.99 hbk.