This article is in the Opinion and Other Articles Categories

Telling the Story of Chernobyl

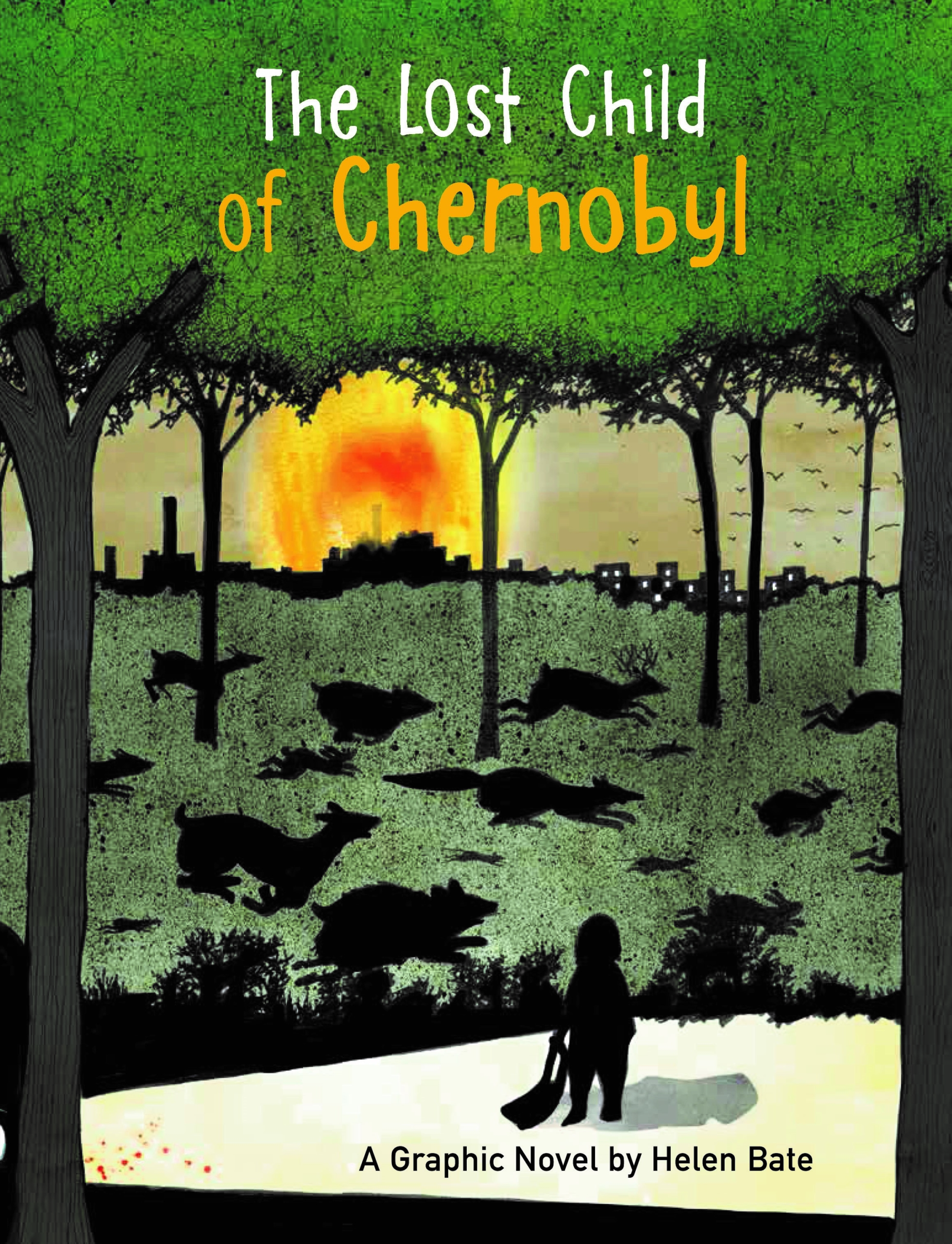

In her graphic novel The Lost Child of Chernobyl, Helen Bate invents a child brought up by wolves in the woods. But it tells the real story of the global environmental disaster at Chernobyl in April 1986. Helen explains the inspiration for the book and how she approached the subject.

The events of April 1986 changed the world for ever. When the nuclear reactor at Chernobyl in Ukraine exploded, national boundaries were no protection from the resulting radioactive cloud. The winds blew it north and west, over many European countries including Belarus, Austria, Hungary and Germany. It travelled as far as Sweden and the UK, causing problems in some areas that will last for hundreds of years. Even in parts of the UK, farmers lived with restrictions on the movement of livestock until 2012.

I was a young mother in 1986. My sister lived in Austria with her two young boys. The explosion at Chernobyl affected them immediately, with sandpits being emptied in public playparks and children not being allowed to play outside for weeks. Many governments had real concerns about the long-term impact of the fallout across Europe and people were frightened.

Twenty years later I had some involvement with a local children’s charity bringing children who had serious health problems from Belarus to the UK for recuperative holidays. My daughter travelled to Minsk with the charity to make a fundraising film that highlighted the on-going health problems the children in Belarus face as a result of the contamination. It was Belarus and Ukraine that suffered the worst of the contamination, and the stories of the disaster and its aftermath have been a lesson to the world. But today, many children are unaware of Chernobyl and what happened there.

As a children’s writer and illustrator, I try to provide children with an understanding of important events from modern history, and difficult social issues that have relevance to their life today. I believe it allows them to see their world in more context. Seeing that many people have overcome terrible adversity, that life continues and is OK again is important, especially in a world where children face a future of increasing global problems.

History allows us to tell this story at a safe distance. Thirty-five years after Chernobyl, the story can be told in ways that remove the fears and the anxiety. But it is still important that the stories are told to new generations. Only by understanding the problems of the past, can we truly understand how we should live in the future. This is as true for Chernobyl as it is for the Holocaust, or for global pandemics.

Graphic novels are great for explaining complex issues in a visual way. They suit many children more used to visual media than previous generations and those who find longer texts off-putting. I want to engage reluctant readers as well as those who like the immediacy of graphic novels. But with those age seven to eleven, the graphic novel requires a more accessible style of storytelling, shorter than traditional graphic novels and more age appropriate.

Graphic novels are great for explaining complex issues in a visual way. They suit many children more used to visual media than previous generations and those who find longer texts off-putting. I want to engage reluctant readers as well as those who like the immediacy of graphic novels. But with those age seven to eleven, the graphic novel requires a more accessible style of storytelling, shorter than traditional graphic novels and more age appropriate.

In ‘The Lost Child of Chernobyl’, I wanted to write a story based heavily in fact. Since watching a wonderful documentary The Babushkas of Chernobyl by Holly Morris and Anne Bogart I’ve been fascinated by the stories of the older women who continued to live (and die) in the forbidden zone. Basing my story around the experiences of Klara and Anna, two fictional sisters who stay behind, allowed me to portray the actual events that took place from their perspective. The book Voices from Chernobyl written in 1997 by the 2015 Nobel Prize winner Svetlana Alexievich, was another fantastic resource with many first-hand stories of what took place after the explosion and crucially, how people felt about their situation.

But how to bring a child into the story? There was no child lost in the forest that night, (as far as I’m aware), but there are many families who have lost children to thyroid cancer as a direct result of the fallout. However, I strongly believe that these stories of personal loss belong only to those children and their surviving families.

I felt that the child in my story should be a mythical child, one that would represent all the children that live in our damaged planet today. For inspiration I looked to the true stories of feral children that have lived with wolves and dogs. The fact that the child in my story never really develops language, and retains a sense of ‘otherness’ is something that’s taken from these true stories. Because the child is also never identified as male or female, it hopefully adds to this sense that they represent childhood itself. This gender-neutral writing was tricky, but a very interesting challenge to undertake.

The traumatic history of the Ukraine was another aspect of history that I felt important to suggest in the story. The reason many women refused to leave the forbidden zone was their past experiences of famine and war. In their eyes no invisible radiation could be as bad as that and I wanted Anna and Klara to be survivors. Anyone reading the histories of Ukrainian children in the 1932-3 Holodomor famine or during World War Two, wouldn’t fail to understand why these old women were unafraid of the radiation, preferring to stay where they had a home, land and water, however polluted. Although these traumatic stories aren’t age appropriate for primary age children, the suggestion of something terrible in Klara and Anna’s past contributes to understanding their sense of acceptance of life in the ‘forbidden zone’.

The lasting message of the book, aims to be that we all need to change our attitude to the natural world. Despite the events at Chernobyl making the land unfit for human habitation, the natural world still evolves and recovers. Although there have been changes in the flora and fauna in the most heavily contaminated areas, the natural world will always adapt and survive. The survival of the human population however, depends on changing the way we live and this is the one most important lesson that I hope comes through in the book, and that we all need to learn.

The Lost Child of Chernobyl, written and illustrated by Helen Bate is published by Otter-Barry Books, £12.99 hbk.