The waiting is over: an interview with Lauren Child

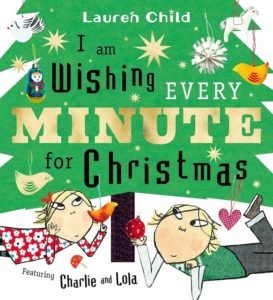

This year marks 25 years since the publication of I Will Not Ever Never Eat a Tomato and, cause for even more celebration, there is a new Charlie and Lola story, I am Wishing Every Minute for Christmas. Nicolette Jones interviewed Lauren Child about her new book, creativity and making Christmas special.

When I meet Lauren Child in her studio behind a pink door, she tells me that her seventh Charlie and Lola book, I am Wishing Every Minute for Christmas, was years in the coming. In fact her dedication says it was 10,512,000 minutes (roughly twenty years). It is apt for a book about waiting.

When I meet Lauren Child in her studio behind a pink door, she tells me that her seventh Charlie and Lola book, I am Wishing Every Minute for Christmas, was years in the coming. In fact her dedication says it was 10,512,000 minutes (roughly twenty years). It is apt for a book about waiting.

Child spent a long time figuring out what she wanted to say. ‘And I think what released me from this block that I had in my head was having written Think Like an Elf, in which Clarice Bean had her kind of Christmas, which is almost a Christmas that goes completely wrong, and because of that, it’s gone right. That’s really what I wanted to talk about in that book: how you have to let it be what it needs to be.

‘And [this picturebook] then became about something else. I’d say it is true of all the Charlie and Lola stories, that the biggest theme is not the one you think it is. So the tomato one really is about fear of the unknown – doing something you have never done before.

‘And this is about how you manage a massive festival when you’re so little and you can’t possibly know what it all means. I think of Lola as about three and a half. She’s probably only got one memory of Christmas at that age.

‘She is excited, but it can be quite overwhelming, a bit like going to a birthday party and becoming so overwhelmed by it that you actually feel sick and want to go home. That seemed a really important thing to think about: how tiny children are with their limited experience of what happens. Then I had to sit with it for a bit.’ Child has after all long been an advocate of the crucial part of creativity that is ‘staring into space’.

In the end Lola’s Christmas is not just the thing that she’s waiting for, but everything she does while she’s waiting for it. Charlie suggests a list of Christmas to-dos. The pre-Christmas activities include writing a letter to Father Christmas, making decorations (paper chains and stars and snowflakes for the windows), singing, ice skating, writing Christmas cards, buying and decorating the tree, opening the doors of an advent calendar, making presents and biscuits, and knitting invisible socks for her invisible friend Soren Lorenson. Also, on Christmas Eve, leaving biscuits out for Father Christmas, and hanging up stockings.

As her book suggests, advocating creativity, Child laments the materialism of modern Christmases, and the immediacy of the gratification: how we now circulate lists with links to Amazon and presents are ordered with a click. Child shows me a letter her mother wrote as a child, which says: ‘Dear Father Christmas, I would like some handkerchiefs, a poetry book and a hairbrush. A Funny Stories calendar and a purse on a strap, please. I’d also like a piano.’ Apart from its hilarious switch from the modest to the ambitious, this letter allowed choices. Which poetry book? What kind of handkerchiefs? The giving was still about selecting.

Child and I discuss the creativity of our own childhoods. We both put on plays (Child with her sisters and cousins), making costumes and props and the ice creams for the interval – lollies made with sticks in ice cube trays. Once her parents even had to listen to a radio play their offspring scripted and performed.

We are also of one mind on the subject of advent calendars. ‘The advent calendar was brilliantly devised to help you manage the days,’ says  Child. We both believe identical chocolates in stamped capsules defeat the point, which is all about anticipation. And the calendar as it should be offers the tiny pleasure of a different daily picture behind a differently-shaped door. In her book, Child has Charlie attach an activity to each day’s image: ‘If there are skates, we’ll go skating’.

Child. We both believe identical chocolates in stamped capsules defeat the point, which is all about anticipation. And the calendar as it should be offers the tiny pleasure of a different daily picture behind a differently-shaped door. In her book, Child has Charlie attach an activity to each day’s image: ‘If there are skates, we’ll go skating’.

Creativity is not only a message of the book, it is also, of course, the medium. Child talks me through the originals of each page, which do not exist online but only as hand-made collages, albeit with some of the pieces (such as small paper snowflakes) cut from printouts. The collage combines drawings and photographs with other elements: hand-colouring, gold and silver star stickers, squares of wrapping paper (as presents), scrunched tissue paper (making the fur of a polar bear), coloured rectangles, fabrics, veneers, graph paper, and rick rack (that wiggly ribbon) evoking paper chains.

Among the objects photographed for the collage are coloured pencils, decorative tape, scissors, sheets of stickers, a wooden ruler, and a plate Child bought in France. The Christmas tree decorations in the book are also photos of the ones Child owns: felt animals, wooden birds, tin hearts, a glass Russian doll. Child turned felt horses into reindeer by gluing on antlers she had drawn. And some of the photos are of objects made as crafts: folded stars and a string of Christmas trees bent in the middle to be 3-D.

As is usual with the Charlie and Lola books, the story is a blend of the real and the imaginary. Lola’s advent calendar becomes the scene she stands in – with little numbered doors to show us it is make-believe. Elsewhere, a bauble with Lola’s features reminds us this is her fantasy. Similarly, Lola rides at the head of a heard of reindeer who all have her eyes. There is a realistic spread of Charlie and Lola walking through autumnal trees – whose bark is made using pastels – followed by an image in which Lola sees herself as the cuckoo in a cuckoo clock, recalling the page in I’m Not Sleepy … when Lola imagines herself as a bird. Child works to make Charlie and Lola’s world consistent, so there are echoes between the picturebooks: a round table with chairs, for instance, is a recurrent motif.

The pictures offer a game in themselves: spotting what is photographed, what is drawn, what is a familiar object put to a different use … It is also possible to take a phone photo of details and zoom in, so the original textures are more obvious – what seems like flat printing, for example, can turn into a bobbly piece of material with a raised surface. This is a book that encourages crafts, and also rewards scrutiny of its crafting techniques.

There were some problems that had to be solved about how to represent Child’s ideas, often with ingenious solutions. How to draw Lola’s invisible friend? Soren is depicted with clear nail varnish. How to conjure ice? After much experimentation, Child scanned something on screen that had a slightly odd texture and a pale grey-green colour that worked very well. Putting Soren on the ice, though, was problematic because the varnished figure looked disturbingly as though he was trapped under the ice. He had to be moved to the edge of the rink. There is a good deal of trial and error, of playing around, in Child’s creations, before she finds what is just right.

Another important aspect of Child’s work is, obviously, that it is funny. Jokes are both visual and verbal: Lola knitting invisible socks, say, and Lola counting people she wants to send Christmas cards to: ‘I know lots of people – at least 75, or maybe even 50’. She also estimates the number of stars she wants to make to put in the windows: twice as much as five. Charlie says: ‘So ten’, and Lola responds ‘Double 5 is 55’.

The finished book is a great aid to whiling away the run-up to Christmas, and to helping very small people manage the massiveness of the festival. And Charlie is right when he says to Lola: ‘Waiting is easier when you forget you are waiting.’ It is also easier, this book proves, when you are laughing.

Nicolette Jones writes about children’s books for the Sunday Times and is the author of The Illustrators: Raymond Briggs (Thames & Hudson); The American Art Tapes: Voices of Twentieth Century Art (Tate Publishing) and Writes of Passage: Words to Read Before You Turn 13 (Nosy Crow).

I am Wishing Every Minute for Christmas by Lauren Child is published by Simon and Schuster, 978-1398542792, £12.99 hbk.