Valediction No.8: Meadows and Muffins

Brian Alderson is donating his remarkable collection of children’s books to Seven Stories. Here he carefully wraps up two of Eleanor Farjeon’s alphabet books.

In 1968 I was honoured with the Eleanor Farjeon Award. It came as a great and, to me, seemingly undeserved surprise for, although I had been ‘messing about with children’s books’ for a number of years that hardly amounted to ‘distinguished service’. Moreover, my reading experience during those exciting times hardly touched on the mass of writing that marked Eleanor’s contribution to the genre.

In an attempted gesture of gratitude to the Children’s Book Circle I was able to spend some time at the Swiss Cottage Library compiling a chronological booklist of Eleanor Farjeon’s publications for children, the seventy or so in Eileen Colwell’s 1961 Bodley Head Monograph being, uselessly, in alphabetical order. The experience brought home what the cognoscenti knew anyway that the diversity of her writing and its illustration demanded an analysis beyond contemporary scholarship.

In an attempted gesture of gratitude to the Children’s Book Circle I was able to spend some time at the Swiss Cottage Library compiling a chronological booklist of Eleanor Farjeon’s publications for children, the seventy or so in Eileen Colwell’s 1961 Bodley Head Monograph being, uselessly, in alphabetical order. The experience brought home what the cognoscenti knew anyway that the diversity of her writing and its illustration demanded an analysis beyond contemporary scholarship.

Seeing the poetry in its original published form brings home its character in a way that such a compendium as The Children’s Bells (1957) cannot. (Published by Oxford and well illustrated by Peggy Fortnum it was a sort of companion to the selected stories in The Little Bookroom (1955), famed for its gaining in dodgy fashion the Carnegie Medal and first winner of the Hans Christian Andersen prize.) A defence of her verses from accusations of slightness by such as Humphrey Carpenter cannot be done through a few quotes and kindly words as given, say, by Morag Styles in her much-praised From the Garden to the Street (Cassel, 1998) but through an examination of its appearance in individual books. Thus the 366 days in the 400 pages of The New Book of Days (1941), marvellously illustrated by Philip Gough and M.W. Hawes, include many poems as well as prose as the seasons progress, and, in same manner, Perkin the Pedlar, with its powerful drawings by Clare Leighton (Faber, 1932) takes us on a topographical tour of Britain from Appledore to Zeal Monarchorum with a tiny story and a poem at every stop. (This lovely book was read to me in Miss Jones’s kindergarten when I was four and may well account for my lifelong appreciation of book-making ever since.)

There were also, of course, books made up entirely of illustrated verses by Eleanor of which in almost continuous print are the Nursery Rhymes of London Town (Duckworth, 1917) illustrated by Macdonad Gill, Eric Gill’s brother, and the comedy of the English crown that she composed with her brother Herbert, Kings and Queens (Gollancz,1932). A fondness for alphabets as a founding principle is manifest elsewhere than Perkin and includes the two volumes noticed here.

There were also, of course, books made up entirely of illustrated verses by Eleanor of which in almost continuous print are the Nursery Rhymes of London Town (Duckworth, 1917) illustrated by Macdonad Gill, Eric Gill’s brother, and the comedy of the English crown that she composed with her brother Herbert, Kings and Queens (Gollancz,1932). A fondness for alphabets as a founding principle is manifest elsewhere than Perkin and includes the two volumes noticed here.

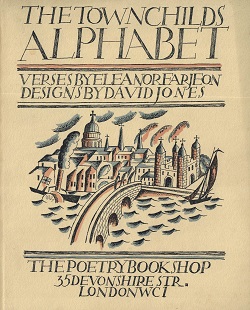

They have a particular appeal as originating from Harold Monro’s Poetry Bookshop which is sometimes stigmatized as ‘Georgian’ thanks to its highly successful anthologies before Uncle Ez and Old Possum stole the show. It published few books for children but had a keen interest in illustrators manifested in the four pages of adverts at the end of our books here where can be found many single sheet Broadsheets and Rhyme Sheets illustrated by artists today being celebrated at the centenary of the Society of Wood Engravers: Philp Hagreen… John Nash… Paul Nash… McKnight Kauffer… and especially the draftsman Lovat Fraser.

Eleanor produced one or two texts for the broadsheets but it is not clear how the two alphabet books were commissioned. Her rhymes are redolent of the period with country children never seeing a tractor or a black plastic bag and town children firmly rooted in the middling classes buying flowers or ice-cream from street traders:

N for Neddy

Go, Neddy, go,

Go up the hill,

With a bag of grist

For the miller’s mill.

Hee-haw! Perhaps I won’t,

Or perhaps I will

G for Gutter-Sweeper

When the snow that first came down

Pure and white is turning brown,

Guttersweepers with their brooms

Come to town.

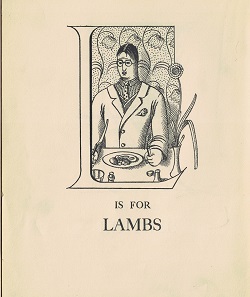

Both books are designed alike with the letter-title and illustration on the verso and Farjeon’s verses on the recto of the page-openings. In both  cases the drawings are done by artists at the start of their careers. William Michael Rothenstein was in fact only sixteen[1] but produced accomplished pencil drawings framed by the letters he was illustrating. Eccentricity showed his remarkable confidence in his skills despite running against some of the verse depictions (one wonders what Eleanor made of the wildly gesticulating blackberry-picker for Jam or, in Lambs, where a gentleman is shown consuming a cutlet.

cases the drawings are done by artists at the start of their careers. William Michael Rothenstein was in fact only sixteen[1] but produced accomplished pencil drawings framed by the letters he was illustrating. Eccentricity showed his remarkable confidence in his skills despite running against some of the verse depictions (one wonders what Eleanor made of the wildly gesticulating blackberry-picker for Jam or, in Lambs, where a gentleman is shown consuming a cutlet.

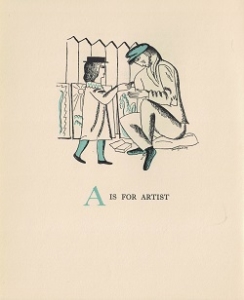

David Jones was on the brink of a more distinguished career, working with Gill at Ditchling before going with him to Wales for great deeds soon after Town Child was published. The wit of his drawings often given a blue tint, and their angular patterning, together with his lettering and design for his front cover, make for a rare but, I think, never -repeated entry into children’s books.

Brian Alderson is a long-time and much-valued contributor to Books for Keeps, founder of the Children’s Books History Society and a former Children’s Books Editor for The Times. His most recent book The 100 Best Children’s Books is published by Galileo Publishing, 978-1903385982, £14.99 hbk.

Bibliography

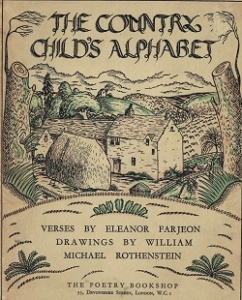

Eleanor Farjeon The Country Child’s Alphabet. Drawings by William Michael Rothenstein. London: The Poetry Bookshop, 35 Devonshire Street, Theobalds Rosd, WC1, 1924. 210×170 mm. [56pp. + 4pp.ads.Books for Children]. Cream paper over boards, cut flush, hand-lettered title and tinted drawing by the artist to front.

Ibid The Town Child’s Alphabet. Designs by David Jones…1924 [description as above]

[1]He would quickly drop the William which was the forename of his father, a notable painter and Principal of the Royal College of Art. One of his brothers, changing his name to Albert Rutherstone in 1914, was a brilliant artist, illustrator and graphic designer.