This article is in the Category

Winnie-the-Pooh: a classic of collaboration

Original drawings of Winnie-the-Pooh are on display at the V&A for the first time in nearly 40 years as part of the UK’s largest ever exhibition on Winnie-the-Pooh, A.A. Milne and E.H. Shepard. In particular Winnie-the Pooh: Exploring a Classic examines the thrilling interplay between text and illustration, shedding new light on the creative collaboration between Milne and Shepard, as curators Emma Laws and Annemarie Bilcough explain.

A. A. Milne and Christopher Robin

The concept of illustration as visual storytelling is particularly important in books for children; while listening to the words and looking at the pictures, they are essentially participating in the narrative process. In the Winnie-the Pooh storybooks, the interplay between text and image plays a crucial role in imparting the narrative. Already in 1928, one contemporary reviewer for the New York Times described A.A. Milne and E.H. Shepard ‘as indispensable one to the other as Sir John Tenniel and Lewis Carroll’

The story of the two men’s collaboration began in 1924 when a mutual friend, E.V. Lucas, suggested to E.H. Shepard that he might illustrate Milne’s verse book When We Were Very Young. Although Milne and Shepard knew of the other’s work, they had not actually met. Their first meeting in 1924 seems to have gone well, as Milne sent Shepard a short note of thanks: ‘If you are always as jolly and as crack right as this, I shall consider myself very lucky in my collaboration.’ It seems from letters exchanged between them that Milne took a close interest in the illustration process, having the illustrations returned to him with each batch of verses and occasionally replying with suggestions for new ones.

By the time Milne was writing his storybook Winnie-the-Pooh, Shepard was accepted as the man who would illustrate it, although J.H. Dowd had illustrated the first story when it appeared in the Evening News on 24 December 1925, and Alfred E. Bestall the second for Eve: The Lady’s Pictorial (10 February 1926). Milne wrote to Shepard: ‘So I have now promised L[ucas] & D[aphne?] a ‘Winnie-the Pooh’ book. I don’t know if you have heard of this animal – Christopher Robin’s bear. It began with a story in the Evening News (illustrated not very well by Dowd); & went on with one in Eve (illustrated very well by Bestall). I hope you have seen neither, for your own sake. I have since written two more – now being typed. I propose a book of 12 such stories, illustrated by E.H. Shepard, bless him.’

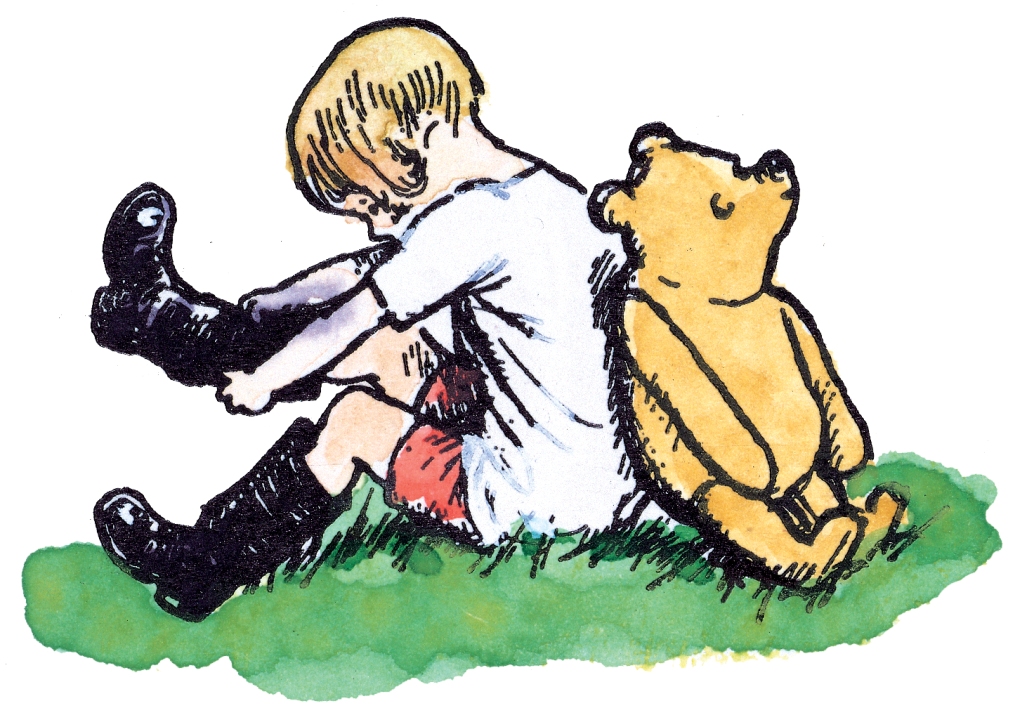

It was important to Milne that Shepard base his illustrations of the characters on Christopher’s own toys and he invited Shepard to his home in Chelsea in June 1926: ‘But I think you must come here on Thursday, if only to get Pooh’s and Piglet’s likeness’. In Winnie-the-Pooh, Milne offers the reader no description of his protagonists. He leaves it to Shepard to introduce – visually – both Christopher Robin and Edward Bear, his teddy, as they come down the stairs – ‘bump, bump, bump’; the result is one of the most familiar and best-loved of the Pooh illustrations. While Shepard’s portraits of Christopher’s toys inspire his character vignettes, he distils their general appearance into outlines and animates them. Occasionally, the odd leg seam betrays their origins. Milne and Shepard continued to exchange ideas in letters and met regularly for Sunday lunch or tea at Cotchford Farm, the Milnes’ weekend cottage in East Sussex.

The imagined world of Winnie-the-Pooh is a curious fusion of fantasy and reality, conjured from the real landscapes of Ashdown Forest near Cotchford Farm. Milne rarely describes the Forest in his stories; instead, Shepard visualises it for the reader. Just as with the toy portraits, Milne was keen for Shepard to see the Forest and they took walks there together several times. Shepard returned again in 1928 to draw, for example, the pine trees at Gills Lap, which inspired the ‘Enchanted Place’ in The House at Pooh Corner. For the famous plan of 100 Aker Wood used for the endpapers to Winnie-the-Pooh; Milne sent Shepard a plan of the topography of his corner of Ashdown Forest and suggested that Shepard place the characters in front of their houses

Shepard’s full-page landscapes play a central role in the scene setting. Milne was evidently appreciative of them since he even altered his text to accommodate the illustration of Eeyore with his tail in the stream when Shepard mistakenly provided a full-page illustration instead of a small vignette.

Excerpts from Winnie-the-Pooh appeared first in The Royal Magazine and Milne and Shepard worked closely with Frederick Muller at Methuen to arrange the layout of the magazine spreads. Some designs made their way into the published book; it was the magazine spread, for example, that prompted the increased height of the arc of bees buzzing above Pooh’s head and arrangement of the text ‘He climbed and he climbed’ to mirror his ascent of the oak tree. Both Milne and Shepard contributed ideas to the page design; Milne in his manuscript introduced the idea of bouncing words to illustrate Piglet bouncing in Kanga’ pouch, while it was Shepard who planned the layout of the friends pulling Pooh out of Rabbit’s door.

Preliminary pencil sketches, and the pen and ink drawings developed from them, demonstrate Shepard’s vigorous draughtsmanship, keen observation, understated humour and delightful evocation of movement and character. Ultimately, however, it is Shepard’s highly inventive response to Milne’s text that singles him out.

Throughout the books, Shepard’s illustrations punctuate the text and alter the pace of Milne’s narrative; in particular, sequences of vignettes prolong the action and contribute to the humour, as when the tablecloth appears to wriggle, wrap itself in a ball and roll across the room. At times, the illustrations replace the text in the storytelling and can be read with or without the text, as when Piglet makes his perilous climb up the string to the letterbox in the ceiling of Owl’s collapsed house.

Shepard’s illustrations also expound details within the text, helping to visualise Milne’s wordplay; even the most experienced readers may initially be bemused by the reference to Eeyore, ‘sitting down on THE WOLERY’. He had a genius for interpreting text ironically – Christopher Robin’s ‘Sustaining Book’, open at the word ‘Jam’, offers nutritional rather than spiritual sustenance to the ‘Wedged Bear in Great Tightness’. Shepard also visually emphasizes Eeyore’s sarcasm; as Eeyore declares ‘it isn’t so Hot in my field about three o’clock in the morning as some people think it is. It isn’t Close, if you see what I mean – not so as to be uncomfortable, It isn’t Stuffy’, in a three-part image, he becomes visually overladen with snow as his sentence progresses.

With a sense of humour similar to Milne’s, Shepard could not resist adding jokes of his own, such as the little mouse who, when helping to free Pooh out of Rabbit’s door, is faced with grabbing hold of a prickly hedgehog and thinks better of joining the effort. He also introduces little incongruities to add dramatic irony, the visual equivalent to the pantomime refrain, ‘It’s behind you!’, letting readers in on a secret – when Pooh and Piglet build a house for Eeyore it is the illustration that reveals the real story – the two friends are shown in fact dismantling Eeyore’s house of sticks before they go to rebuild it on the other side of the wood.

Winnie-the-Pooh: Exploring a Classic is curated by Annemarie Bilclough and Emma Laws and runs until 8 April 2018. Tickets are £8 (concessions and family tickets available). V&A Members go free. Advance booking is advised – in person at the V&A; online; or by calling 0800 912 6961 (booking fee applies).

A new V&A publication, Winnie-the-Pooh: Exploring a Classic, written by Annemarie Bilclough and Emma Laws, accompanies the exhibition. Copies are available in the exhibition shop and online.

Winnie-the-Pooh, The House at Pooh Corner and When We Were Very Young are published by Egmont, £14.99 hbk.