Price: £12.99

Publisher: Faber & Faber

Genre: Fiction

Age Range: 14+ Secondary/Adult

Length: 208pp

- Illustrated by: Danica Novgorodoff

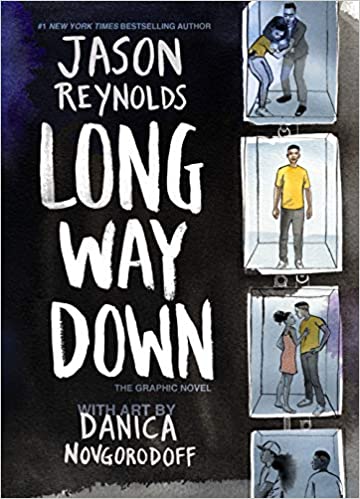

Long Way Down: the Graphic Novel

Illustrator: Danica NovgorodoffLong Way Down was Jason Reynolds’ first book to be published in the UK, a free verse novel that took on urban violence and probed its emotion and complexity. Now released as a graphic novel with illustrator Danica Novgorodoff, this new format of the action gives rise to further thought and draws in a new cohort of readers, reluctant and fluent.

Reynolds’ gift is in the ability to write how children think. Readers relate because the protagonist feels like one of them, in this case, a young boy called Will. When his brother, Shawn, is gunned down in front of him, Will knows the rules. No crying. No snitching. Revenge. He takes his brother’s gun, gets in the elevator and prepares to go take his vengeance. Except, in the sixty seconds and seven floors it takes to get down to the ground floor, Will is joined by people from his past. Dead people. And Will has to question everything he’s ever been taught.

Novgorodoff’s ink and watercolour illustrations lend a softness to the faces, giving an empathetic glow to their expressions, which contrasts bittersweetly with the violence in the text, and the depiction of the darker shadowy side of bullets and guns. Yet also, there is a chaos to the graphics, as they break out from their lines and boxes, bordering occasionally on the abstract, and this serves to complement the succinct yet powerfully emotive text from Reynolds. The emotions swerve from surprise to relief, from confusion to love to grief. Sometimes full pages are left with a single image for the reader to contemplate, investing time in the power of the story, and understanding that the plot unfolding in the elevator spreads its message beyond – mirroring Novogorodoff’s breaking out from the constraints of borders. The colour choices are wise too – Will’s stark yellow top against a dark blue/grey exploration of the other images, and the very real violence of splashes of red when it is used.

And yet the images don’t diminish Reynolds’ careful word play, which toys with repetition and poses many questions, causing the reader to empathise with Will’s confusion, and finally to question themselves too. The reader is sucked into the environment of the elevator itself, feeling both Will’s suffocation under the grip of grief, and yet also the liberation of having moral choice.