Price: £16.98

Publisher: The Bodleian Library

Genre: Fiction

Age Range: 14+ Secondary/Adult

Length: 464pp

Buy the Book

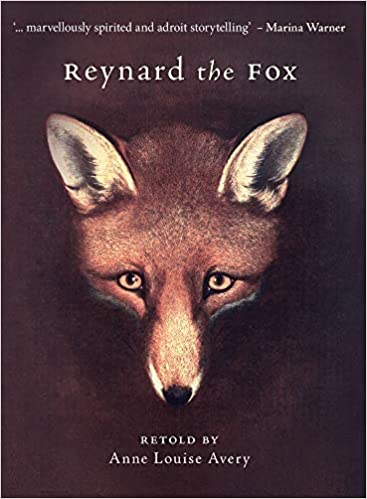

Reynard the Fox

The medieval saga of Reynard the Fox, tremendously popular in the Middle Ages and again in the nineteenth century, has fallen out of favour in recent decades. James Simpson published a version in 2015, which I haven’t read, but otherwise this new retelling by Anne Louise Avery is the first for a long, long time.

Perhaps the first thing to say in a review for Books for Keeps is that this story of a wily Fox, his enemies the Wolf and the Bear, and their tempestuous monarch the Lion, is in no way a book for children. I had forgotten how cartoonishly cruel the humour is. Maybe some children would be amused by that. But there is also a lot of satire of medieval religion which, to be honest, isn’t that amusing even for an adult.

And yet, this is a tremendous achievement on the part of Anne Louise Avery, who has breathed fresh life into a moribund classic. She has based her translation on Caxton’s 1482 version, but there are many elements that are hers alone. She really enjoys herself, for instance, with a Rabelais-esque list of the victuals Bruin the Bear packs ‘for a light morning repast’, including ‘several pawfuls of sour green gooseberries’. This is the first of many such lip-smacking lists of culinary delicacies. These modern additions reflect and refract one of the overriding themes of the book, hunger and greed. As the adder says, ‘The great necessity of hunger may cause both men and animals to break their oaths. That is the way of things.’

But the essence of the book is not food but language. Where Caxton uses a particularly relishable word such as ‘slonked’ for swallowed, Avery tends to retain it, allowing the context to suggest the meaning, although there is also a handy glossary at the back of the book. She also adds many of her own verbal curlicues, so Caxton’s ‘He shoved the table away from him’ becomes ‘he shoved the table over with a thunderhorn-clatter-ban’.

Language is the cunning Reynard’s secret weapon, weaving ‘word-lace’ to get himself out of many a tight spot: ‘Word by word, he had fine-crafted his own miraculous escape out of nothing but the night air and a string of syllables.’

A very welcome addition to the original book is the author’s finely-tuned appreciation of the Flanders landscape, ‘the cross-hatch of dyke and stream and ditch, their waters ribbons of flint and quicksilver and fennel in the heat.’ Avery’s descriptions of the characters in their own landscape are vivid and resonant, and owe almost nothing to Caxton.

While some will find the long-winded legal arguments tedious, others will be entranced by ‘the skein-frill of a fine fox-turned phrase’.