Price: £12.99

Publisher: Jonathan Cape

Genre: Fiction

Age Range: 8-10 Junior/Middle

Length: 192pp

Buy the Book

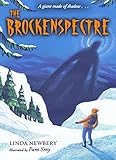

The Brockenspectre

Illustrator: Pam SmyThis book is inviting to the hand; comfortable, even. Around 160/70 words to the pages; sometimes fewer when they are decorated by Pam Smy’s romantic Swiss mountain scenes, nudging the print aside to share the space, or claiming entire double page spreads. The prose is comfortable too, telling the story – at first – with the directness and simplicity of a fable. Just right for readers growing used to enjoying a novel on their own.

Niklas Rust, people say, is the best guide in the mountains. Tourists come to his village to join the groups he leads; they arrive by pony and trap, for these are the Alps of a while ago. Niklas works with his craft, ‘his whistle and his compass and his rope’, rather than a mobile or laptop to check the weather. There’s no suggestion in the illustrations of sophisticated mountain kit; sweaters rather than Hi-Tec gear.

Tomas is Niklas’s son; that’s his cornerstone. Time and again, as the story unfolds, he reminds himself, ‘I am the son of Niklas Rust’. The family idyll for Tomas, his Mamma and little Johanna is threatened, though, for Niklas is always restless for the high peaks. When poor weather keeps his clients away, his frustration erupts into bad temper and he’s gone, sometimes for weeks on end. This time, weeks become months, without a word. Tomas is cruelly mocked about his absent father at the village school (well, maybe, but kids mostly know when to lay off, and a parent’s death is no teasing matter). A year after his father’s disappearance, Tomas leaves a note for Mamma, and with some bread, cheese and apples, a water bottle, an extra sweater and a spare pair of socks, he’s off to search for Pappi.

Niklas has taught Tomas respect for the mountains, including warning him of the Brockenspectre, the mysterious monster of the peaks. In his nightmares, Tomas fears the creature has taken his father; yet also, ‘Tomas knew, it was inside him.’ It takes him only two days to find his father; or rather, his grave and, living in a hut nearby, the kindly grandmother he never knew he had. His adored father turns out to have been secretive, untrustworthy. There are consolations, for Tomas and his new grandmother find each other and Tomas finds himself (‘He was Tomas Rust’). He returns to the village with renewed love for his mother and even, it seems, to a home which might be shared with ‘kind, reliable, Max’, the village carpenter. He has also found a natural explanation for the Brockenspectre, realising the ‘monster’ is awe-inspiring only in its beauty; in one of the poetic interludes which punctuate the narrative, the spectre tells Tomas, ‘Fear me only as you fear yourself…I am you’.

The fable has become a novel with psychological complexities and with this shift come expectations of literal credibility. Maturing young readers cross-question texts, wondering, ‘Yes but…’ Here, for example, they might well ask, ‘Yes but, after a few weeks, wouldn’t they have sent out search parties, even for an expert mountaineer?’; and ‘Yes but, wouldn’t a guide’s son setting off for days in the mountains take more than a snack, a sweater and some socks?’; and ‘Yes but, how could Niklas’s mother live only two days from the village, and yet nobody seems to know she’s there – and how does she get her supplies to survive a snowed-in winter?’

Even so, there’s much for a thoughtful reader to discover and enjoy – perhaps about knowing yourself, about parents and their fallibilities, about the dialogue you can share with a place.