Price: £6.99

Publisher: Allen & Unwin

Genre: Fiction

Age Range: 10-14 Middle/Secondary

Length: 228pp

Buy the Book

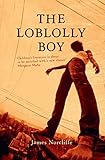

The Loblolly Boy

At any one time, there is only one loblolly boy. However, this status can be passed on from one child to another, through an Exchange. When the Exchange takes place, the child becoming the loblolly boy should really want to change, possibly because of a threat or danger, otherwise it won’t work. The attributes of a loblolly boy? Invisibility, the ability to fly – and a complete lack of appetite. Appearance? ‘Dark green cape, sage-coloured shirt and leaf-green leggings’; ‘feathery green wings’; ‘like an angel the colour of avocado’; ‘as old as the tree’; large green eyes ‘filled with all the sadness of the world’.

This is the premise of Norcliffe’s story, which introduces a new mythical figure to children’s literature. The children that we see undergoing the Exchange are from fractured families, the main protagonist, Michael, having been left at a children’s home that combines modern institutionalisation with Poor Law incarceration. All are ‘Sensitives’, having the ability (denied to the rest) of being able to see the loblolly boy. However, as the loblolly boy’s guardian, Captain Bass, points out, in going from sad child to loblolly boy ‘the trade-off is the loss of human contact’ and being ‘tricked out of your real existence’. By Exchanging, Michael may have escaped his previous life, but he feels depressed, alone and bored – ‘a great nothingness’. However, this state does eventually lead him to a family where he’s at home – provided he can effect another Exchange and ‘escape into the real world again’. Meanwhile, he has to avoid the attentions of the Collector, ‘tall and bent with narrow stovepipe trousers and a strange-looking black frock-coat’ who looks like he’s ‘stepped from some nineteenth-century storybook’. This sinister figure can see the loblolly boy through special glasses, and regards him as the ultimate addition to his collection of dead butterflies.

The story combines such archetypal figures from Romantic/Gothic literature with some abrasive realities from the present. These include children living on crisps and fish and chips, bullying and, perhaps most significantly, an implication of child-abuse in the figure of the Collector (who is accused at one point of being a ‘pervert’). Confusions over identity abound, and a contrast is drawn between the ‘free spirits’ of Michael’s adoptive family and the authoritarian school that they attend. An ingenious plot-device relates to a child’s toy, the significance of which is revealed, like Citizen Kane’s ‘Rosebud’, only at the end. There is some repetition and expository dialogue but, overall, this is an intriguing and unusual book, part fairy-tale, part social comment.