An interview with Dhonielle Clayton

Dhonielle Clayton grew up in the Washington, DC, suburbs on the Maryland side and is a former secondary teacher and librarian. She is a New York Times bestselling author, the COO of the non-profit We Need Diverse Books, and the owner of Cake Creative Kitchen. Darren Chetty interviewed Dhonielle for Books for Keeps.

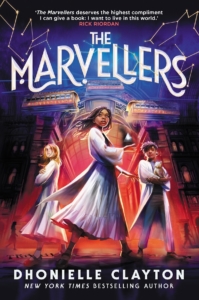

The Marvellers tells the story of eleven-year-old Ella Durand, the first Conjuror to attend the Arcanum Training Institute, a magic school in the clouds for Marvellers from around the world. Ella discovers that being the first isn’t easy but she finds friendship in fellow misfits Brigit, a girl who hates magic, and Jason, a boy with a fondness for magical creatures and support from her Elixirs teacher, Masterji Thakur.

The Marvellers tells the story of eleven-year-old Ella Durand, the first Conjuror to attend the Arcanum Training Institute, a magic school in the clouds for Marvellers from around the world. Ella discovers that being the first isn’t easy but she finds friendship in fellow misfits Brigit, a girl who hates magic, and Jason, a boy with a fondness for magical creatures and support from her Elixirs teacher, Masterji Thakur.

Then the notorious Ace of Anarchy escapes prison, supposedly with a Conjuror’s aid, and Ella finds herself as the prime suspect. Worse, Masterji Thakur mysteriously disappears while away on a research trip. With the help of her friends and her own growing powers, Ella must find a way to clear her family’s name and track down her mentor before it’s too late.

Can you tell us a little bit about the Marvellers and their relationship with the conjurers?

The Marvellers are a magical group of people that have something called a ‘marvel’ which is their light (aka magic) inside of them and they live in three cities that move about in the skies above. The Conjurors are magical people that are descendants from West African Marvellers. The Transatlantic Slave Trade changed their magic, turning their marvel light into a twilight because of the horrific atrocities and pressure that was put on them due to the pain and struggle of that experience and the subsequent experiences post-emancipation. Those things changed their light. As the Conjurors were trying to enter the Marvellian society and escape having to deal with the non-magical (the Fewels), Marvellers were like ‘Your magic is a little too different for us, a little too strange. So, we don’t want you really living with us. You can come in and out of our communities. You can work. You can’t live here. Your children can’t go to school with our children, but we’ll still let you tend to our children. We will enjoy your food and your music, but that’s all. You must go home to your cities and neighbourhoods on the ground.’ This relationship between these two magical communities has been fraught because one has been excluded.

And with Ella’s arrival, it’s also a story of integration, isn’t it? Would you expect children reading the book to make the connection with Brown vs Board of Education or is that something that that they won’t necessarily do as they’re reading it?

That’s for adults to make that connection. Kids will understand being left out, and maybe as they learn about Brown versus Board of Education and Ruby Bridges, they might start seeing some of those parallels of kids (and entire communities) systematically being left out and people being ostracized for being different. The parallel is definitely something I intentionally wanted to press down on and create an analogue for, but my greatest hope is that this echo enables adults to have deeper conversations with their young people about how people are historically marginalized and left out in communities all over the world. At its core, the series is about outsiders and insiders, and the human need to create these sorts of distinctions. And so, if kids pick up on these analogues, that’s great. That’s like an extra little layer of cookie that they can get versus it being hammered on their heads as a Public Service Announcement.

How would you characterize Ella to someone who hasn’t read the book?

Ella is perfect kid in your classroom. She’s the one you wish you were when you were 11. She’s the person that’ll be the friend with the kid that’s quiet or grumpy. She’s the one that puts a smile on your face that’ll hand out the papers. She’s the ultimate lovebug and an extraordinary global citizen. If you don’t have friends, she’ll always offer you a branch of friendship. No matter the bad weather, she’s going to look for the sunshine.

But Ella faces a huge challenge at the start of the book: She straddles two worlds and functions like a tiny bridge between them. The Marvellian world is uneasy about Conjuror integration into their cities and their school, because for over 300 years they’ve been afraid of how magic manifests in the Conjuror world. Conjure folk remain hurt by and suspicious of Marvellers, leaving many Conjurors torn about whether they should even share space with a group of people who have actively kept them out and ostracized them.

Ella is caught in this emotional, political and social tangle, not unlike how my parents dealt with being the first generation of Black Americans to integrate segregated schools in the American South. She is also the only one of her kind at the Arcanum Institute, much like I was one of very few Black kids in every school I attended. Like I did, she has the pressure on her to be a representative of her race at all times, making sure to maintain a pleasant, lovely disposition to remain non-threatening to navigate the system. As a young person, I was focused on making sure I could make it through the American school system without being penalized and marginalized in a way that would affect my trajectory going to college and university.

Ella must be steadfast and actively hold onto her joy when so many wish to take it from her.

What was the background to you deciding to write this book?

I wanted to write a magic school book, which is a perennial trope of children’s literature — I have a masters in children’s literature — it is something that is an evergreen that keeps coming up over and over again as a setting for many children’s books. Everyone told me it couldn’t be done. That there was no space for another magic school book.

But there are always so many children missing from those particular stories. It’s as if the invitations to BIPOC, BAME, LGBTQIA+, neurodivergent, disabled kids, etc, seem to get lost in the mail, and those children are perpetually waiting, lost in the margins. So, I wanted to use my world to talk about what the future of magic could look like when all kids are accounted for, and there’s a place for them to be centred and feel included. What does a global magic school look like where all of the kids of the world come?

This came directly from my experience as a secondary school librarian in New York City. My students (and their parents) hailed from all over the world. My school felt like the world was represented within it, and I wanted to pay homage to those young readers who came into my library constantly looking for themselves in magical landscapes and never found themselves.

You’ve created a very multicultural cast. What kind of preparation did you need to do to write such a diverse cast?

I live a diverse life. My friends are a wonderful tapestry of various cultures. They speak many different languages and come from so many different places. I am lucky. Also, my dad’s family was in the military and he grew up in and out of America as my grandfather was stationed around the world, so he gave me a global perspective early on, pressing upon me that America is not the centre of the world. So as the spoiled brat that I was (*cough still am), I was fortunate enough to spend many summers abroad, traveling to the UK, Ireland, the Caribbean, Central and South America. I lived in Japan and in France. These experiences shaped me and made me realise very quickly that a global perspective was way more interesting than solely an American one. I met people from all over the world and their lived experiences had a profound impact on me.

Also, I wanted to make sure that my students could see the bits and pieces of their lived experience so I based many characters off of them. I did tons of research. I had tons of authenticity reads. I believe in going to experts to get the representation correct. I had about 13 different authenticity reads. It took me 7 drafts and 8 years to write this book to get it right.

You initially struggled to find a UK publisher for this book. Was it that they thought there literally wasn’t an audience, or that the very act of publishing it would be seen as like an act of aggression, as though the book is a critical commentary on the Harry Potter books in the form of fiction?

I think it was both. I honestly think the UK publishing community didn’t think that the UK reader was ready to leave Hogwarts. The shadow of Hogwarts is massive — and the fandom can be toxic when threatened (if you could see the hate mail and death threats I get from Potterheads, oof). I got many comments that the world of The Marvellers wouldn’t stand out when everyone just wanted to be at Hogwarts. I couldn’t help thinking, but what about those of us that aren’t welcome there. Like me! What about the BAME and LGBTQIA+ kids who literally are afterthoughts or caricatures in that world? What about the racism, anti-indigenousness, and antisemitism that permeates the wizarding world’s fundamental worldbuilding as we leave the UK and expand globally?

I get it. The UK is very protective of this juggernaut of children’s literature and her legacy. Publishing The Marvellers could be seen as an act of aggression and critical commentary on the Harry Potter universe because it includes all the children J.K. Rowling marginalized, stereotyped, and frankly, forgot. But I’m not writing to be in conversation with her or her world, though it may seem like it and I can’t seem to escape the comparisons. I’m writing for the children that are not seen by her, and that are not seen in general. When I was building the Arcanum Institute for Marvellous and Uncanny Endeavours, I was thinking about my students in New York City, Paris, Japan, D.C., and anywhere I taught. The ones desperate to see themselves. And if there’s a white English writer that the UK must compare me to, then let it be Philip Pullman. As a children’s scholar, His Dark Materials series made me question the possibilities of children’s literature. His work became a northern light (pun intended) for me as a young creator wanting to make something layered and complex for young people to sink their teeth into.

But in closing, I must say, when marginalised creators (especially Black writers) enter the publishing machine, we are often siloed and seen as ‘topical’ and ‘niche’ and never universal. My imagination and the world of The Marvellers was seen as a thing that wouldn’t find an audience in the UK the way white content creators get to have automatic global appeal. The history of British colonisation and thus global Anglophilia means that white British stories get to live in the imaginations of children worldwide while the rest of our stories get to be trotted out to teach lessons on racism during Black History Month.

If I can engage with Harry Potter, a British person can engage with The Marvellers. Frankly, that’s how I feel about it!

Darren Chetty is a teacher, doctoral researcher and writer with research interests in education, philosophy, racism, children’s literature and hip-hop culture. He is a contributor to The Good Immigrant, edited by Nikesh Shukla and the author, with Jeffrey Boakye, of What Is Masculinity? Why Does It Matter? And Other Big Questions. He tweets at @rapclassroom

The Marvellers by Dhonielle Clayton is published by Piccadilly Press, 978-1800785472, £7.99 pbk.