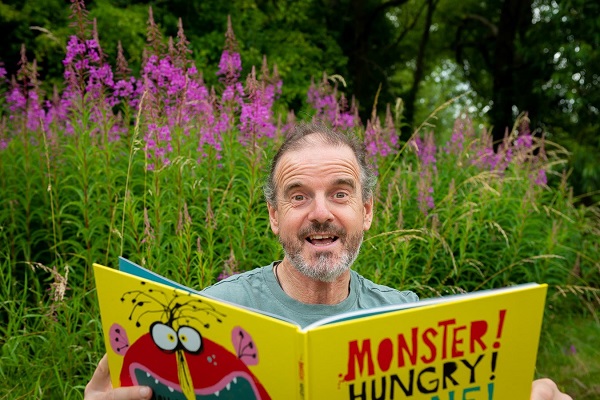

Authorgraph No.258: Sean Taylor

Sean Taylor interviewed by Clive Barnes

The writers of picture books can easily pass under the radar. I don’t mean those picture book creators who both write and illustrate, but those  who write stories for others to illustrate. Yet there are only a very few talented writers who can pitch a story perfectly for the youngest children and their parents, and who offer space and possibility for an illustrator’s imagination: people who understand how a picture book works. Sean Taylor has been providing such stories for over fifteen years for a number of publishers and a variety of illustrators.

who write stories for others to illustrate. Yet there are only a very few talented writers who can pitch a story perfectly for the youngest children and their parents, and who offer space and possibility for an illustrator’s imagination: people who understand how a picture book works. Sean Taylor has been providing such stories for over fifteen years for a number of publishers and a variety of illustrators.

Sean remembers feeling surprised that he had written a poem at the back of ‘a rather boring lesson’ when he was sixteen or so, but he also remembers the sense of freedom it gave him, and he has been writing ever since. It has been a winding path, ‘following his bliss’, as he says, quoting the American Jungian mythologist Joseph Campbell. The path reached an early turn back in 1990s London when Sean joined The Basement Writers, a group which had been associated with Chris Searle and other radical writers about twenty years before. Sean was a performance poet at the time and his first published book was poetry for adults. In 1994, he made his debut as a children’s author, winning second prize in a competition sponsored by The Independent newspaper and Scholastic publishers. This brought him to The Catchpole Agency, run then by Celia Catchpole and now by her son James, a small agency specialising in children’s books. Sean generously credits the support and advice that Celia and James have given him as crucial to a career which has seen him publish over sixty books since.

Over mushroom soup, bread and cheese, Sean tells me that he believes writing picture book texts has an affinity with writing poetry, ‘saying as much as you can with as few words as you need.’ And he works hard at achieving that economy. There’s a lot of redrafting, working on different aspects of the story until it’s right, enjoying the concentration and experimentation: ‘I do like that process. Once I focus in, I’m happy. Even if I have to throw things away, that’s fine.’ His major frustration is finding the time to write. ‘With children and our older parents to think about, perhaps I’ve now reached the age of responsibility.’

Sean has ‘a great passion’ for picture books, which he sees as one of the new art forms to arrive in the last century, and he sees himself as part of that movement. He has an interest in older picture books, seeking them out on visits to the British Library. We spend a while talking about some of the pioneers. A chat in which Maurice Sendak naturally turns up for his economy and resonance. When I ask what rules he might have for writing a successful picture book story, Sean resists the idea of rules, but offers an off-the-cuff checklist instead. For instance, does it have ‘a character for children to fall in love with’ from the opening sentence? Does it have a page turning quality? Does it have a satisfying, uplifting ending, perhaps a surprise or a twist? …. If there’s not enough emotion in the story, for instance, I’ll try to work out how to heighten the emotion.’ When we further explore what might have contributed to his gift for this kind of storytelling, he considers that his work in schools as a teller of traditional tales might have provided him with a feel for the structure of a story. ‘After all, a picture book has to be able to be told aloud and actually perhaps it is a way of keeping the oral tradition alive in new circumstances.’

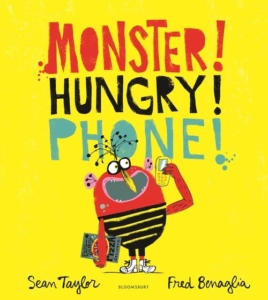

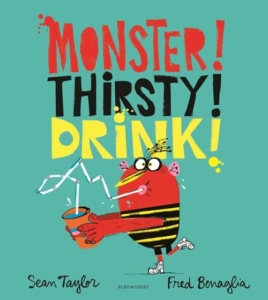

In Sean’s recent story, Monster! Hungry! Phone! illustrated by Fred Benaglia, we can perhaps see some of this at work. This features a shouty central character of few words whose desperate ringing for a take-away is repeatedly thwarted by wrong numbers. Monster is a character whose frustration children and parents can identify with and also feel free to laugh at. It’s a story which uses few words but is structured by the sequence of phone calls and is full of noisy refrains – Monster’s demands, the tap, tip, tap of the phone keys, followed by the bling, bling, bling of the ringing at the other end – and the inventive unhelpfulness of the replies, of which my favourite is ‘This is the voicemail of Simon Sloth. I’m sorry, I’m probably asleep. If you’d like to leave a short message, please speak after the beeeeep.’ There’s a companion story out now, Monster! Thirsty! Drink! which is every bit as unmissable.

In Sean’s recent story, Monster! Hungry! Phone! illustrated by Fred Benaglia, we can perhaps see some of this at work. This features a shouty central character of few words whose desperate ringing for a take-away is repeatedly thwarted by wrong numbers. Monster is a character whose frustration children and parents can identify with and also feel free to laugh at. It’s a story which uses few words but is structured by the sequence of phone calls and is full of noisy refrains – Monster’s demands, the tap, tip, tap of the phone keys, followed by the bling, bling, bling of the ringing at the other end – and the inventive unhelpfulness of the replies, of which my favourite is ‘This is the voicemail of Simon Sloth. I’m sorry, I’m probably asleep. If you’d like to leave a short message, please speak after the beeeeep.’ There’s a companion story out now, Monster! Thirsty! Drink! which is every bit as unmissable.

It is rare for Sean to work directly with an illustrator. Typically, the publisher will send one of his stories out to an illustrator that looks right for it. Sean is frequently surprised and delighted by how it is re-imagined. ‘Always a surprise. You might have a picture in your head and it is never that picture that comes back.’ It is relatively rare for Sean to feel that an illustrator has got it wrong, however different their vision. ‘Everything has to work towards the story being easy to read aloud and being a fulfilling experience for a child. Only if anything works against those two things, will I intervene.’ Sometimes, it should be said, Sean can set quite a challenge for an illustrator. In Hoot Owl, Master of Disguise, a self-important owl disguises himself as, among other things, a carrot, a sheep and a bird bath: an off-the-wall idea which might partly explain why it took so long to be published, until rescued by Walker Books master editor, David Lloyd. Then, imaginatively realised by illustrator Jean Julien, Hoot Owl went on to be an award winner and a best seller, and was followed by two other books from Sean and Jean.

It is rare for Sean to work directly with an illustrator. Typically, the publisher will send one of his stories out to an illustrator that looks right for it. Sean is frequently surprised and delighted by how it is re-imagined. ‘Always a surprise. You might have a picture in your head and it is never that picture that comes back.’ It is relatively rare for Sean to feel that an illustrator has got it wrong, however different their vision. ‘Everything has to work towards the story being easy to read aloud and being a fulfilling experience for a child. Only if anything works against those two things, will I intervene.’ Sometimes, it should be said, Sean can set quite a challenge for an illustrator. In Hoot Owl, Master of Disguise, a self-important owl disguises himself as, among other things, a carrot, a sheep and a bird bath: an off-the-wall idea which might partly explain why it took so long to be published, until rescued by Walker Books master editor, David Lloyd. Then, imaginatively realised by illustrator Jean Julien, Hoot Owl went on to be an award winner and a best seller, and was followed by two other books from Sean and Jean.

Sean says he welcomes collaboration and happily works towards that ‘bit of magic’ which, for him, makes a collaboration ‘better than the sum of its parts’. His latest partnership is with Bristol naturalist and writer Alex Morss, who lives just round the corner from Sean. Between them, they have now written four natural history books. They began with the crowd-pleasing title Funny Bums, Freaky Beaks & Other Incredible Creature Features for primary school age children. Now they have three books on the seasons for younger ones, all illustrated by Cinyee Chiu, a Taiwanese illustrator. Winter Sleep, Busy Spring and Wild Summer have appeared already; and the draft of Sean’s contribution to the fourth, about Autumn, lay on the floor when we went up to his writing eyrie in the roof to continue our chat

Sean describes his writing imagination as a kind of garden, where he finds unexpected things growing. About ten years ago, he wrote a well-received novel for teenagers A Waste of Good Paper, based on his experience of working with children with emotional and behavioural difficulties. And there’s always a possibility something similar may spring up in the future. At the moment, though, he has returned to poetry, with three books coming out in the next year, each with a different illustrator. Again intended for younger children and their parents, they arose from what he describes as a difficult time in his own life when he felt he only had space for poetry. Sean presented me with a copy of the first of the trio, The Dream Train, a beautifully produced collection of poems for that quiet time before sleep, stunningly illustrated by Anuska Allepuz. Full of warmth and humour, it is a gentle and reflective book. Sean’s mother died recently, and these poems honour the memory of his childhood bedtimes with her. It is a work which, like Grandma’s knitting in Sean’s poem The Blanket, ‘has a little bit of love in every stitch’. Look out for it.

Clive Barnes has retired from Southampton City where he was Principal Children’s Librarian and is now a freelance researcher.

Monster! Hungry! Phone! and Monster! Thirsty! Drink! by Sean Taylor, illustrated by Fred Benaglia, are published by Bloomsbury Children’s Books, £6.99 pbk.