Authorgraph No 263: Sophie Anderson

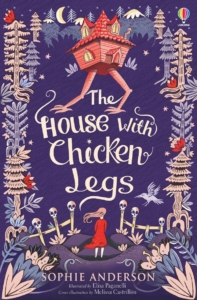

‘I was so nervous about everything, I was quite overwhelmed by it all,’ Sophie Anderson tells me, speaking over Zoom from her home in the Lake District. We are reminiscing about our first meeting, back in 2017, when I interviewed Sophie for The Bookseller magazine ahead of the publication of her debut children’s book, The House With Chicken Legs. It was clear from the start that this was something special. Early proof copies of the book were already attracting rave reviews; Waterstones had selected it as Children’s Book of the Month, and the book went on to be shortlisted for almost every major award that year including the Carnegie Medal, the Branford Boase Award and both the Blue Peter and British Book Awards. ‘Publishing was all so new,’ Sophie recalls. ‘I didn’t grasp how much Usborne were investing in me, how being Waterstone’s Book of the Month would launch my career…it was a whirlwind of a rollercoaster.’

The House With Chicken Legs is a reimagining of the Baba Yaga story, told from the perspective of her 12 year-old granddaughter. Marinka lives with her grandmother in a house with chicken legs that periodically stands up in the night and moves without warning. Bab Yaga’s job is to prepare and guide the spirits of the dead between this world and the next, but Marinka longs for a normal life and sets out to forge her own destiny. The book reworks the traditional Slavic folktale into a story of identity, love and belonging, woven together by Sophie’s lyrical prose and magical storytelling.

The House With Chicken Legs is a reimagining of the Baba Yaga story, told from the perspective of her 12 year-old granddaughter. Marinka lives with her grandmother in a house with chicken legs that periodically stands up in the night and moves without warning. Bab Yaga’s job is to prepare and guide the spirits of the dead between this world and the next, but Marinka longs for a normal life and sets out to forge her own destiny. The book reworks the traditional Slavic folktale into a story of identity, love and belonging, woven together by Sophie’s lyrical prose and magical storytelling.

This idea of reimagining traditional tales had long been at the heart of Sophie’s writing, inspired by her grandmother who had fled post-war Germany to marry a Welsh man. Sophie recalls their house, filled with Prussian folk patterns, music, food and, above all, stories from Eastern European countries. Before she was published, she remembers exploring writing for different age groups and experimenting with voices but once signed to Usborne Sophie worked very hard, with her agent Gemma Cooper and editor Rebecca Hill, to establish the right feel for the book. ‘Some people in publishing might call it building a brand,’ she explains. ‘We wanted it to have a fairytale feel so it was Rebecca’s idea to remove all the place names and mentions of time and anything that was too modern, so that it could have a timeless feel.’ This sensibility of reimagined folktales tapping into universal themes has carried through to her other books.

That first editing process was also invaluable in establishing her voice and pitching Sophie’s writing at the right level for children. ‘The very first

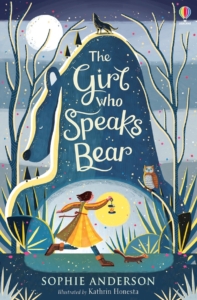

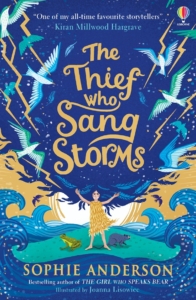

That first editing process was also invaluable in establishing her voice and pitching Sophie’s writing at the right level for children. ‘The very first draft of The House With Chicken Legs was probably too old and too dark,’ she remembers. ‘Rebecca helped me get it to the right tone for its readers (9 to 12 year olds).’ Darker themes resonate throughout her books, from death in The House With Chicken Legs to grief in The Thief Who Sang Storms and trauma in The Snow Girl, but are always handled thoughtfully and with great care. ‘We should never write down to children,’ she asserts. ‘They know about death, they have trauma … we don’t want to shy away from that, we want to talk about it openly and honestly but we want to wrap it up in a nice, comfortable way so that they can read about it feeling safe.’ The power of the human spirit is at the heart of Sophie’s writing: characters such as Olia in The Castle of Tangled Magic find great resilience and courage, new friends nourish Yanka in The Girl Who Speaks Bear. And above all there is always hope, a tonic in a world where we are constantly blasted with negativity. Hope, Sophie believes, is what sets middle-grade fiction apart. ‘The endings don’t have to be happy, necessarily, but they do need to be hopeful in some way. No matter how dark things are you need to have some hope there. I think we all need that.’

draft of The House With Chicken Legs was probably too old and too dark,’ she remembers. ‘Rebecca helped me get it to the right tone for its readers (9 to 12 year olds).’ Darker themes resonate throughout her books, from death in The House With Chicken Legs to grief in The Thief Who Sang Storms and trauma in The Snow Girl, but are always handled thoughtfully and with great care. ‘We should never write down to children,’ she asserts. ‘They know about death, they have trauma … we don’t want to shy away from that, we want to talk about it openly and honestly but we want to wrap it up in a nice, comfortable way so that they can read about it feeling safe.’ The power of the human spirit is at the heart of Sophie’s writing: characters such as Olia in The Castle of Tangled Magic find great resilience and courage, new friends nourish Yanka in The Girl Who Speaks Bear. And above all there is always hope, a tonic in a world where we are constantly blasted with negativity. Hope, Sophie believes, is what sets middle-grade fiction apart. ‘The endings don’t have to be happy, necessarily, but they do need to be hopeful in some way. No matter how dark things are you need to have some hope there. I think we all need that.’

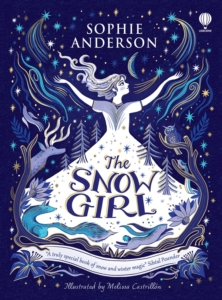

The Snow Girl, published by Usborne this autumn, is Sophie’s fifth novel and is clearly close to her heart. She had long loved the story of a girl made of snow who comes to life and counts Eowyn Ivey’s adult novel Snow Child as one of her favourite books. ‘That’s inspired by the same fairy story,’ she explains, ‘and I thought it would be nice to do a middle grade version of it. it’s a lovely story, lots of beautiful imagery and the message is essentially living life to the full.’ In Sophie’s version, Tasha and her parents have recently moved to live with her grandfather, who is struggling to cope with running his farm. Following an incident the previous year, Tasha now finds it difficult to make friends and feels isolated in her new home. One wintry night she and her Grandpa build a snow girl and Tasha longs for her to come to life. That same night she does, and the two girls become friends. In early drafts Tasha was scared or in disbelief of the magic but Sophie realised her reaction didn’t chime with the spirit of the book. ‘As a grown up there’s that feeling that magic can’t be real and you’re a bit wary of it, but that was the moment I found Sasha’s voice: this is going to be a girl who just believes the magic can happen and it doesn’t need to be explained. It’s a wish that comes true.’ Together Tasha and Alyana, the snow girl, explore an enchanted icy land on starlit nights, conjuring the kind of winter magic that makes for a classic Christmas gift. That sense of a book that could be shared with all the family was very much in Sophie’s mind. Her own children range in age from 5 to 17: ‘I wanted to write a book that someone like me could take and read to all their kids.’ This is the first time Sophie’s work has been published in hardback in the UK and the foiled jacket, beautiful two-colour illustrations by Melissa Castrillon and slightly shorter chapters than her previous books help to create that feel of book to read aloud to the family on a cold night.

The Snow Girl, published by Usborne this autumn, is Sophie’s fifth novel and is clearly close to her heart. She had long loved the story of a girl made of snow who comes to life and counts Eowyn Ivey’s adult novel Snow Child as one of her favourite books. ‘That’s inspired by the same fairy story,’ she explains, ‘and I thought it would be nice to do a middle grade version of it. it’s a lovely story, lots of beautiful imagery and the message is essentially living life to the full.’ In Sophie’s version, Tasha and her parents have recently moved to live with her grandfather, who is struggling to cope with running his farm. Following an incident the previous year, Tasha now finds it difficult to make friends and feels isolated in her new home. One wintry night she and her Grandpa build a snow girl and Tasha longs for her to come to life. That same night she does, and the two girls become friends. In early drafts Tasha was scared or in disbelief of the magic but Sophie realised her reaction didn’t chime with the spirit of the book. ‘As a grown up there’s that feeling that magic can’t be real and you’re a bit wary of it, but that was the moment I found Sasha’s voice: this is going to be a girl who just believes the magic can happen and it doesn’t need to be explained. It’s a wish that comes true.’ Together Tasha and Alyana, the snow girl, explore an enchanted icy land on starlit nights, conjuring the kind of winter magic that makes for a classic Christmas gift. That sense of a book that could be shared with all the family was very much in Sophie’s mind. Her own children range in age from 5 to 17: ‘I wanted to write a book that someone like me could take and read to all their kids.’ This is the first time Sophie’s work has been published in hardback in the UK and the foiled jacket, beautiful two-colour illustrations by Melissa Castrillon and slightly shorter chapters than her previous books help to create that feel of book to read aloud to the family on a cold night.

In her research for The Snow Girl, Sophie explored the evolution of the story, from ancient tales to modern interpretations. There was, she tells me, an old pagan goddess called Morana, a goddess of winter in Slavic folklore who had to die to give birth to spring. ‘To me that’s the snow girl,’ she says, ‘and this is my version of it. As always I’m standing on the shoulders of other storytellers and I always want to express some gratitude for this long line of storytellers who have carried this story across thousands of years so that I can play with it today.’ I ask if her own understanding of the story has changed during the writing process? She had an idea, she says, of what the original story meant to her when she first read it, but that perception has evolved over time. ‘If I were to read The Snow Girl now I would think about my children leaving home,’ she observes. ‘I like the idea that different people will read my books and take away different messages. You want to have that ambiguity. If you write something that is essentially an authentic human experience then people will relate to it and take their own message from that.’ The overarching message she feels, is one of living life to the full. ‘A short full life is more preferable to a long empty life.’

Looking ahead, Sophie admits that all the ideas in her head come from old folk and fairy stories, particularly the ones from Eastern Europe that feel part of her heritage. Why does she think we continue to be so drawn to these stories in modern times? ‘There’s a reason these stories have survived for so long. Essentially, it’s because they all relate to those common human experiences. It’s comforting to think that thousands of years ago people were experiencing the same trials, they had the same hopes and dreams and fears and tribulations.’

Fiona Noble is a books journalist and reviewer, specialising in children’s and YA literature, for publications including The Bookseller and The Observer.

Books mentioned, all published by Usborne

The House With Chicken Legs, Usborne, 9781474940665, £7.99, pbk

The Girl Who Speaks Bear, 9781474940672, £7.99, pbk

The Castle of Tangled Magic, 9781474978491, £7.99, pbk

The Thief Who Sang Storms, 9781474979061, £7.99, pbk

The Snow Girl, illus by Melissa Castrillon, Usborne, 9781803704357, £12.99, hbk