This article is in the Category

Coming Home: An Interview with Michael Rosen

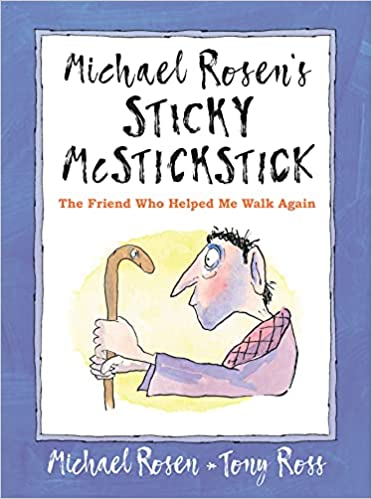

After being admitted to hospital in 2020 with coronavirus, Michael Rosen had to learn to walk again. The story is told for children in his new picture book, Sticky McStickstick: The Friend Who Helped Me Walk Again. Nicolette Jones interviewed Michael about the book for Books for Keeps.

After being admitted to hospital in 2020 with coronavirus, Michael Rosen had to learn to walk again. The story is told for children in his new picture book, Sticky McStickstick: The Friend Who Helped Me Walk Again. Nicolette Jones interviewed Michael about the book for Books for Keeps.

The last two public events I chaired before lockdown in 2020 were with Michael Rosen. These were not his last events – he went on to take part in more, including school visits, was out and about, and, as we all know, contracted Covid and then spent 40 days in a coma. So the first Zoom event we shared this year, when he was well enough again, involved bunting and a trumpet fanfare. And I am still so delighted to see him on Zoom, after all the dangers he has passed, that I find myself grinning inappropriately even as he talks about the legacy of his illness: the sight he has lost in one eye, the hearing in one ear and the feeling in his toes. And his occasional episodes of feeling ‘weak and feeble’. Though obviously none of this is a smiling matter. But he joins in, by joking about his lapses of memory: some part of his brain has been affected, he says, that houses names of people he knows very well, and extremely famous film stars. Tom Cruise, George Clooney and Meryl Streep have been suddenly irretrievable.

This astonishing capacity to address pain with humour is what gave rise to his new book, Sticky McStickstick: The Friend Who Helped Me Walk Again, a picturebook written with levity that nevertheless prompts a lump in the throat. It is about the people (and the personified walking stick) that helped him regain the use of his legs. Tony Ross’s pictures also introduce laughs to this distressing experience, just as Rosen did when he made the physios in the rehabilitation centre smile by naming his walking aid, and then Tweeted about it, to make his wider audience of anxious followers smile too. Some suggested this sounded like material for a book, and the idea was born.

Wherever George Clooney has been hiding in his head, Rosen seems as sharp and fluent as ever. Extraordinarily, he is also now back on the live performing circuit. He has given hour-long shows back-to-back for hundreds of children at the Children’s Book Show, and signed books at the Muswell Hill Children’s Bookshop. He was in Cheltenham to receive his CliPPA award for On the Move, his collection of Poems about Migration, assembled before the pandemic but published in October 2020. He is being given this year’s J M Barrie Award in person. Besides, he has appeared in the ITV documentary The Story of Us, and been a vocal presence on social media and in the papers. This interview is the latest of many, for print and online. (He finds sitting and talking to people, he says, easier than going up and down stairs.)

Wherever George Clooney has been hiding in his head, Rosen seems as sharp and fluent as ever. Extraordinarily, he is also now back on the live performing circuit. He has given hour-long shows back-to-back for hundreds of children at the Children’s Book Show, and signed books at the Muswell Hill Children’s Bookshop. He was in Cheltenham to receive his CliPPA award for On the Move, his collection of Poems about Migration, assembled before the pandemic but published in October 2020. He is being given this year’s J M Barrie Award in person. Besides, he has appeared in the ITV documentary The Story of Us, and been a vocal presence on social media and in the papers. This interview is the latest of many, for print and online. (He finds sitting and talking to people, he says, easier than going up and down stairs.)

He has also been astonishingly prolific since he came home in June 2020. He wrote a story in his head while he was still in hospital, which comes out in April: Rigatoni, the Pasta Cat. He wrote his bestselling chronicle of having Covid, including the parts he never knew about, pieced together from medics’ accounts and the nurses’ diary: Many Different Kinds of Love. In the pipeline are more picturebooks, as well as a collaboration with Michael Foreman about a correspondence between an English boy and a Polish boy during the Second World War.

But just out is Sticky, which, he says, ‘breaks the major rule of picturebooks, that the protagonist should be a child or a surrogate child. Walker Books, though, said ‘That’s alright’. I think they themselves had created the path that made that possible, with the Sad Book, in which Quentin Blake represented adult me.’ Rosen has a theory that ‘most children’s books are in actual fact part of the conversation that we have in society about nurture and education’. And Sticky McStickstick has a place in that conversation about how any of us might be cared for.

Once the idea arose out of the joshing of rehab and a few daft Tweets (a picture of Sticky asleep in bed, for instance) that the stick might become a picturebook character, Rosen thought: ‘What’s the story?’ ‘And then, of course, I realised. The story is that this grown-up has had to learn how to walk. Which is of itself quite odd, and almost funny. Because we think of two-year-olds learning how to walk, or baby animals. And then I thought well it’s got these phases as well: trying to stand up, the frame, the wheelchair, the stick, and there’s even the positive ending of coming home. And so it grew.’

In that way that is characteristic of Rosen, his thoughts open out quickly from quite simple to very sophisticated. Suddenly we are discussing the healing power of tragedy and comedy, as a way of exploring the human condition, in Shakespeare in particular. Although tragedy is reputed to be the cathartic one, Rosen finds comedy ‘more portable and more comforting’.

I am impressed not only by the humorous approach to Rosen’s trauma, but by his positivity, as he has kept out of the story his grief and loss – and rage. Because it is clear from his social media posts that he feels rage at the government for its callous and incompetent handling of the pandemic.

‘I think it’s because I compartmentalize it. So I’ve got the rage bit, I’ve got the grief bit and I’ve got the compassion bit and I try not to let one affect the other. I don’t want the anger to affect how much I feel grateful for the people who did so much to keep me alive. And the grief bit: I don’t want to dump on people and say “take my grief from me”. My grief is mine and I must own that.’

Grief, Rosen thinks, is best shared with those who have gone through something similar, otherwise ‘it’s too much for people’. After his son Eddie died, he addressed groups of parents who had lost children. ‘They might think “I feel helpless and hopeless and so does Michael Rosen”.’ And now he is part of an online group of sufferers of long Covid. ‘That’s not dumping, it’s sharing.’

I wondered if Rosen, who had processed grief before, and written The Sad Book, found it helpful now. ‘Yes. I think it did help me. The bit about making sure I do something I am proud of every day.’

Unlike Quentin Blake’s images in The Sad Book, Tony Ross’s pictures in Sticky are not portraits of Rosen and his family. Did they discuss this? ‘My guess is Tony wanted to universalize it. We don’t have conversations; Tony gets on and does it. Whereas Quentin did want to make it my personal experience. Tony has widened it out and it’s given him leeway to have fun and not be tied to exactly what happened.

‘And I suppose the text does tend a bit towards the folkloric, the emblematic. It’s not a characterful text. It’s more as we tell folk stories: this happened and then this happened.’ Rosen universalizes it too by talking in a coda about the general experience of illness and getting better and being helped. ‘Maybe you’ve been ill. Or maybe you know someone who’s been ill,’ he writes.

We discuss finding ‘chiming moments’ in books as a way for young people to connect with them. ‘Everything I know about good teachers is that they do that,’ he says, so literature opens up conversations – ‘in your head or in class’.

‘One of the images that informed me is the fact that when you have a major illness – and this happens to everybody so it’s not just me – is that all the apparatus of everyday life, everything from shopping to family relationships to clothes, all sort of falls away. And you become the thing that Lear talks about, a ’poor forked creature’. Just your body. My world when I came out of the coma was no bigger than my body in the bedclothes.

‘In the rehab hospital it got a bit bigger because there is the wheelchair, the stick, the zimmer and these people saying, you could do this, you could do that. But it’s so tiny really. It’s insulated. I would talk to Emma [his wife] and the kids; Emma was allowed into the rehab hospital a couple of times, but then they disappeared and so even when they said ‘we’re in the middle of lockdown’, I wasn’t really listening because I was being busy being a poor forked creature.’

Rosen agrees that there is a connection with On the Move, because being just the poor, forked creature is akin to being in exile, stripped of family and home and habits and possessions.

He is hopeful that the CLiPPA win will mean the book is used in teaching migration, the Holocaust, the Second World War, family life … And ‘show that poems can be about things that matter, but that may not be funny’. ‘In a sense I’m a victim of my own success and of course they want me to be more funny. But no one person is 100% funny. Just as no one person is 100% anything. That’s important to pass on to children because they’re all going through various forms of labelling. They’re being told they are of this ability, they’re naughty or they’re good. And the kids are all labelling each other. I’m hoping there will also be a sort of Unlabelling. So that that bloke who does ‘Chocolate Cake’ is also that bloke who has these kinds of experiences in his family.’

Nicolette Jones, writer, literary critic and broadcaster, has been the children’s books reviewer of the Sunday Times for more than two decades. Her latest book, The American Art Tapes: Voices of Twentieth-Century Art by John Jones and Nicolette Jones is out now.

Nicolette Jones, writer, literary critic and broadcaster, has been the children’s books reviewer of the Sunday Times for more than two decades. Her latest book, The American Art Tapes: Voices of Twentieth-Century Art by John Jones and Nicolette Jones is out now.

Sticky McStickstick: The Friend Who Helped Me Walk Again by Michael Rosen and Tony Ross is published by Walker Books, 978-1529502404, £12.99 hbk.