This article is in the Category

Yes You Can!

Alex Strick

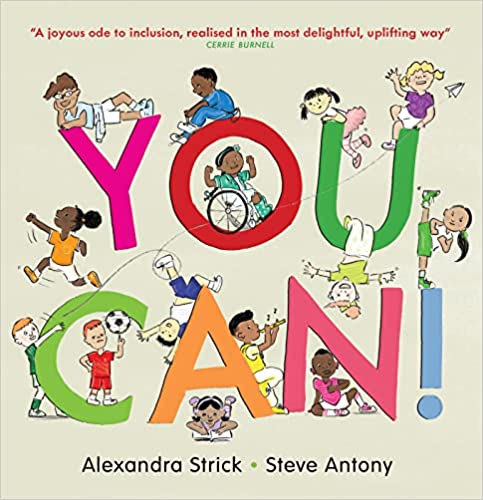

You Can!, by Alexandra Strick and Steve Antony, uses real children’s voices in a genuinely inclusive picture book that reminds all children that they are individuals with the power to decide their own futures. Rebecca Butler interviews Alex Strick about the book.

My first question to Alex Strick is why the message in You Can! was important to her and her readers. She explains it’s because she wanted to empower young readers to believe that it was OK to be themselves and to have the confidence that they can achieve their dreams. Her illustrator Steve espoused the same message.

In the text Alex includes a message that readers can enjoy a picture book at any age. While consulting children for this book she discovered that many had internalised the message that to enjoy a picture book after the age of seven was seen as negative. By then they should be reading text only. Some children mentioned that they actually hid their picture books from the adults because they felt ashamed of reading them. Alex and Steve were determined to counter this message as strongly as possible.

I next asked Alex about the process of creating the book. I heard that the process was lengthy – in fact it took seven years – and could be described as ground-breaking. Alex does not remember when the first idea of the book germinated but the first draft of the book took shape four years ago. The essential idea of the book was that it should be rooted in the experience of children the same age as the intended readers, starting with how those children think and feel. It is designed to feed back to them their own experience, with guidance on how to handle that experience. To achieve sufficient depth it was not enough to base the research on just one cohort of children. There was an iterative process by which the results of one set of children were tested against another’s. In total a hundred children contributed to the eventual outcome.

The text of Alex’s book is sparse in relation to the imagery, especially since the book deals with complex issues. I asked Alex why the text was so slender. The idea of the book from the very beginning was that of a dual narrative, pictures and text going together to form a powerful whole. The illustrator, Steve Antony, led Alex to an understanding of the sheer power of visual imagery to convey significant messages to young readers. The balance between prose and imagery in the book was intended both to convey to young readers the urgency and immediacy of a visual narrative and to avoid the danger that readers unused to lengthy narratives would suffer from what Alex terms prose fatigue.

Although some of the images in the book depict disabled characters, the word disability never appears in the text. I asked why. Her answer is that the book is not about disability. It is about all children, in whatever categories society may place them. The same principle holds not only for children but for adults. The book is designed to stress that all people have a common heritage, not to identify issues that split society into categories that easily become divisive.

Were there themes omitted from the book which in retrospect Alex wished she had included? A significant array of ideas arose during the gestation of the book. One concern had the potential to overwhelm all others, namely the children’s desire to save the planet. This idea does appear in the visual narrative but it had to be kept in balance. When ideas were rejected it was often because they were too specific – don’t eat this kind of food. The aim of the book was to help young readers develop their own principles, not to deliver adult to child injunctions. Alex has no regrets about what is included and what is not.

In the illustration that refers to Gay Pride there is a character in a blue shirt bearing a symbol which I failed to recognise. Alex informed me it was the symbol for transgender identity, namely the gender symbols for male and female together.

My next question followed on. At the end of the book symbols appeared connected with Gay Pride. A teacher, especially in church schools, might comment that children of the age the book is designed for are too young to be introduced to the complex questions of gender and sexual identity. Alex stated that most children would simply enjoy the display of flags and symbols without examining the issues they represent. If some children understand the significance of certain flags, this means that they beginning to become aware of issues that have a powerful reality in the world where they are growing up. Alex does not recognise a controversial element in this educative process.

Finally I asked Alex what was her next project. She replied that the current book has generated ideas stimulating further research and perhaps a further volume. For example, You Can! emphasises that it is OK for children to feel angry or sad. They would benefit from guidance on how to handle anger or sadness. There is also a website on which the children record their thoughts, available at www.theyoucanbook.com. The children themselves are an unfailing source of inspiration for Alex and Steve.

Dr Rebecca Butler writes and lectures on children’s literature.

Dr Rebecca Butler writes and lectures on children’s literature.

You Can! is published by Otter-Barry Books, 978-1913074609, £12.99 hbk.