Life, Comfort and Joy: An Interview with Ruth Brown

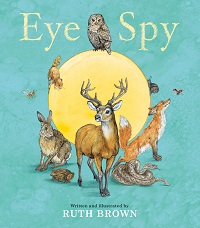

A new picture book from Ruth Brown is always a treat and her latest Eye Spy is certainly that, combining as it does Ruth’s art and her expertise with picture book text. Ferelith Hordon interviews Ruth about her long and distinguished career.

I caught up with Ruth Brown in her London flat. It is spacious and welcoming with a studio room where the large windows allow plenty of light. There are pictures on the walls; none by her though several by both of her sons who are practising artists and by her grandson who looks to follow in the family tradition. But what about Ruth? What was her background? Her early childhood was spent first in Devon, in Silverton where she was born, then Bournemouth. The family moved to Germany in 1947 to Frankfurt after her father took up an administrative post there. ‘We came from a cottage in Devon to a council flat in Bournemouth then to a huge requisitioned house in Germany.’ They later moved to Cologne where she went to school. It was a very relaxed, inclusive upbringing with a ‘progressive’ education. The shock of coming back to Bournemouth School for Girls when the family returned to England was considerable. ‘That was more of a culture shock than going to Germany when I was six.’

I caught up with Ruth Brown in her London flat. It is spacious and welcoming with a studio room where the large windows allow plenty of light. There are pictures on the walls; none by her though several by both of her sons who are practising artists and by her grandson who looks to follow in the family tradition. But what about Ruth? What was her background? Her early childhood was spent first in Devon, in Silverton where she was born, then Bournemouth. The family moved to Germany in 1947 to Frankfurt after her father took up an administrative post there. ‘We came from a cottage in Devon to a council flat in Bournemouth then to a huge requisitioned house in Germany.’ They later moved to Cologne where she went to school. It was a very relaxed, inclusive upbringing with a ‘progressive’ education. The shock of coming back to Bournemouth School for Girls when the family returned to England was considerable. ‘That was more of a culture shock than going to Germany when I was six.’

At school the only place she felt any comfort or freedom was the art room with a very good art teacher. She hadn’t grown up surrounded by picture books, only had Rupert Annuals in the cottage and in Germany they had made puppet shows to illustrate history. ‘I didn’t draw much,’ says Ruth, ‘but what I remember vividly most of all is being small in the cottage in Devon … I was more or less confined to the front garden and used to spend most of my days leaning on the wall watching our neighbour dig up worms.’

She left school at 16 to go to Bournemouth Art College for a very traditional course. From this she moved to Birmingham Art School where  she was directed to illustration – then called Graphic Design. It was here she met her husband, Ken. Then came a move to the Royal College in London in 1961, ‘a bit of an eye opener’ she comments. Students might be asked to design a dashboard for a car or a digital typeface. ‘I think it taught me to see and to think about things in a different sort of way and gave me confidence – they treated you as an adult.’ The good thing was that it was very structured. She cites the Pre-Raphaelites as an inspiration not just for the painting but for the sound drawing that underlies all their work. She feels this discipline is vital for any artist: ‘You can do anything at all if you can draw, but it is not always recognised.’ What does she use to create the rich landscapes and vibrant images that populate her books? Acrylic is always the base – occasionally concentrated watercolour. ‘I use anything I can work with but always acrylic.’ It is fascinating to learn her late husband Ken only worked with watercolour. ‘I can’t,’ she says – nor does she use the computer in the creation of her books. The images are drawn meticulously on transparent paper then transferred to art paper. They are made to size. It will take about six months to bring a picture book to fruition.

she was directed to illustration – then called Graphic Design. It was here she met her husband, Ken. Then came a move to the Royal College in London in 1961, ‘a bit of an eye opener’ she comments. Students might be asked to design a dashboard for a car or a digital typeface. ‘I think it taught me to see and to think about things in a different sort of way and gave me confidence – they treated you as an adult.’ The good thing was that it was very structured. She cites the Pre-Raphaelites as an inspiration not just for the painting but for the sound drawing that underlies all their work. She feels this discipline is vital for any artist: ‘You can do anything at all if you can draw, but it is not always recognised.’ What does she use to create the rich landscapes and vibrant images that populate her books? Acrylic is always the base – occasionally concentrated watercolour. ‘I use anything I can work with but always acrylic.’ It is fascinating to learn her late husband Ken only worked with watercolour. ‘I can’t,’ she says – nor does she use the computer in the creation of her books. The images are drawn meticulously on transparent paper then transferred to art paper. They are made to size. It will take about six months to bring a picture book to fruition.

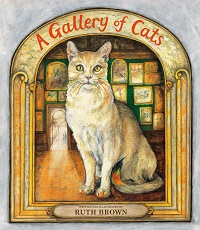

Her first picture book appeared in 1979, Crazy Charlie published by Klaus Flugge at Andersen Press. It was a response to the birth of her  second son and the success of Pat Hutchins’ Rosie’s Walk. She had been working as a freelance illustrator for the BBC on Playschool, Jackanory, Words with Pictures. Now she was reading to two children every night, ‘I found the picture books available very traditional. I ended up quite tired reading to a 6-year-old and a baby, dreading them pulling out a long story … I always have in mind me as a rather tired mother with one child who can read and one child that can’t read. It’s got to be a story that interests me … short, succinct and to the point and not talking down. Maybe the older child can read it themselves later on but there is enough in the pictures to interest the non reader – that has always been my principle.’ Though she has illustrated for other authors and sometimes feels that her drawings for them are better, she likes to write her own text. It gives her complete control. She particularly likes to create double page spreads that spill off the edges, ‘I am always curious about what is slightly out of the page.’ Animals feature prominently in her work, especially cats and dogs. ‘You can get over any emotion using animals’ she says. For her it allows a certain freedom. ‘In a way it is limitless what you can do – I don’t think there is anything I can’t draw.’ She uses photographs, models and draws from life, her grandson for example is the child in A Gallery of Cats. This was the book that brought her back to illustrating after the death of Ken when for a time it was difficult. It was fun to make. ‘I am quite a positive person’ she comments, ‘but I am interested in dark things, like The Dark Dark Tale with its traditional text.’ She wrote this immediately after the death of her mother perhaps reflecting a particular childhood nightmare and it is extremely different from her first book. But even here the ending reverses the fear. Life, comfort and joy are never far from any book by Ruth.

second son and the success of Pat Hutchins’ Rosie’s Walk. She had been working as a freelance illustrator for the BBC on Playschool, Jackanory, Words with Pictures. Now she was reading to two children every night, ‘I found the picture books available very traditional. I ended up quite tired reading to a 6-year-old and a baby, dreading them pulling out a long story … I always have in mind me as a rather tired mother with one child who can read and one child that can’t read. It’s got to be a story that interests me … short, succinct and to the point and not talking down. Maybe the older child can read it themselves later on but there is enough in the pictures to interest the non reader – that has always been my principle.’ Though she has illustrated for other authors and sometimes feels that her drawings for them are better, she likes to write her own text. It gives her complete control. She particularly likes to create double page spreads that spill off the edges, ‘I am always curious about what is slightly out of the page.’ Animals feature prominently in her work, especially cats and dogs. ‘You can get over any emotion using animals’ she says. For her it allows a certain freedom. ‘In a way it is limitless what you can do – I don’t think there is anything I can’t draw.’ She uses photographs, models and draws from life, her grandson for example is the child in A Gallery of Cats. This was the book that brought her back to illustrating after the death of Ken when for a time it was difficult. It was fun to make. ‘I am quite a positive person’ she comments, ‘but I am interested in dark things, like The Dark Dark Tale with its traditional text.’ She wrote this immediately after the death of her mother perhaps reflecting a particular childhood nightmare and it is extremely different from her first book. But even here the ending reverses the fear. Life, comfort and joy are never far from any book by Ruth.

So what next? Is there another picture book to come? The spreads were already there waiting for the colour- so Knock, Knock, Who’s There? Ruth Brown, of course.

A Gallery of Cats, Ten Little Dogs and Ruth Brown’s new picture book Eye Spy are published by Scallywag Press.

Ferelith Hordon is editor of Books for Keeps.