This article is in the Beyond The Secret Garden Category

Beyond the Secret Garden: All About Hair

In the latest in the Beyond the Secret Garden series, Darren Chetty and Karen Sands-O’Connor examine depictions of Black people’s hair in children’s books.

It is not uncommon for children’s books, in Britain and beyond, to feature characters who are identified by their hair or stories their hair plays a significant role in events. Descriptions and depictions of long, flowing hair have often been part of stories about princesses and contributed to dominant notions of womanhood and beauty.

For centuries, where Black people’s hair has been described in British children’s fiction it has often been in dismissive terms, whether as ‘woolly’ as in Anna Laetitia Barbauld’s.Evenings at Home.(1791-6), G.A. Henty’s A Roving Commission; or, Through the Black Insurrection in Hayti (1900), Nina Bawden’s On the Run (1964); or ‘frizzy’ as in Michael Morpurgo’s A Medal for Leroy (2012).

The politics of Black British hair and clothing gained increased attention in the 1970s with the rise of Rastafari and Black Power movements. Paul Gilroy, in There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack quotes from the 1981 Scarman report. Lord Scarman led the inquiry into the 1981 Brixton riots; Scarman suggested that ‘young hooligans’ (Gilroy 135) had appropriated the symbols of the Rastafarian religion, ‘the dreadlocks, the headgear and the colours’ (135) to excuse their destructive behaviour. Scarman was not the only one to believe that dreadlocks were associated with criminality; Sally Tomlinson, in Race and Education, points out that schools debated whether or not to ban dreadlocks (49) in the late 1970s and early 1980s. A young person’s hair and dress were a political and particularly anti-authoritarian statement, one that faced censure from official government institutions such as the police and the schools.

The politics of Black British hair and clothing gained increased attention in the 1970s with the rise of Rastafari and Black Power movements. Paul Gilroy, in There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack quotes from the 1981 Scarman report. Lord Scarman led the inquiry into the 1981 Brixton riots; Scarman suggested that ‘young hooligans’ (Gilroy 135) had appropriated the symbols of the Rastafarian religion, ‘the dreadlocks, the headgear and the colours’ (135) to excuse their destructive behaviour. Scarman was not the only one to believe that dreadlocks were associated with criminality; Sally Tomlinson, in Race and Education, points out that schools debated whether or not to ban dreadlocks (49) in the late 1970s and early 1980s. A young person’s hair and dress were a political and particularly anti-authoritarian statement, one that faced censure from official government institutions such as the police and the schools.

Sympathetic children’s authors took note of the tension between Black British young people and the police, and often this included depictions of Rastafari hair and head coverings. Dan Jones’s illustrations for Inky Pinky Ponky (edited by Mike Rosen and Susannah Steele in 1982), for example, showcases several children with Rastafari tams of green, gold and red, and Black children with locs. These children often are shown interacting with the police, and although the same is true for white people in the book, the end result is different for Black children. A double-page spread in the middle of the book demonstrates this clearly. On the left-hand side is the poem, Don’t go to granny’s (n.p.); the reason not to go to granny’s is that ‘There’s a great big copper’ waiting there. The picture by Jones shows a white child in a cowboy outfit being held by a policeman. On the right-hand side of the page is I’m a little bumper car (n.p.); the accompanying illustration has a child with dreadlocks riding in a bumper car and being confronted by the police. However, whereas the white child, according to the rhyme, will get off with a fine (or possibly a bribe) – the policeman will ‘charge you half a dollar’ (n.p.) – the Black child is jailed for drinking ‘a small ginger ale’ (n.p.). Jones uses the texts chosen by Rosen and Steele to portray the unequal treatment by the police toward Black youth, particularly Rastafari youth. Lorraine Simeon, in her book Marcellus (originally published in 1984), shows how the fear and suspicion of dreadlocks can filter down to younger children as well, when the title character covers his hair with a baseball cap because he worries that his hair might be the cause of his being bullied or beaten up.

Medeia Cohan’s Hats of Faith (2017) includes the ‘Rasta Hat’ as a religious, rather than a political, symbol; the book also features Sikh turbans and patkas, and Muslim hijabs. Denene Milner’s biography of Sarah Breedlove Walker for the Rebel Girls franchise, Madam C. J. Walker Builds a Business (2019), is tellingly titled. Although Walker built her business on creating and marketing hair care products for Black women, the biography focuses on Walker as a businesswoman rather than on hair. The front cover illustration, by Salina Perera, also de-emphasises hair, showing a woman standing over a washtub with a wooden spoon, stirring.

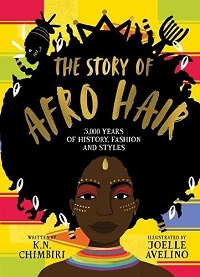

The Story of Afro Hair, written by KN Chimbiri and illustrated by Joelle Avelino, was published by Scholastic in 2021, (eight years after  Chimbiri’s Secrets of the Afro Comb, which she published through her own company, Golden Destiny). In a beautifully presented book, Chimbiri takes the reader though 5,000 Years of History, Fashion and Styles from Ancient Africa, to medieval Africa to European colonization to the emergence of Afro hair care entrepreneurship. Chimbiri also looks at Walker as a businesswoman, but her much shorter biographical sketch includes two pieces of information that Milner’s story does not. First, that Walker visited several Caribbean nations in order ‘to expand her business to other countries where people had Afro hair’ (40); this detail gives Walker a wider global significance than Milner, an American author, provided. Second, Chimbiri points out that Walker’s original difficulties with hair loss were partly due to stress. Stress is also the cause of Marietta’s hair loss in Patrice Lawrence’s short story A Bob and a Weave, written as part of New Class at Malory Towers, an update of the Enid Blyton stories. Marietta is worried about her mother, a boxer, who has been having mental and emotional difficulties since being knocked out in a fight. ‘I couldn’t stop thinking about it,’ Marietta tells another character, ‘That’s when my hair started falling out’ (37). While she initially tries to hide her hair loss with a wig, she is found out by the other girls and, eventually, encouraged to be open about her story and the physical effect it has on her.

Chimbiri’s Secrets of the Afro Comb, which she published through her own company, Golden Destiny). In a beautifully presented book, Chimbiri takes the reader though 5,000 Years of History, Fashion and Styles from Ancient Africa, to medieval Africa to European colonization to the emergence of Afro hair care entrepreneurship. Chimbiri also looks at Walker as a businesswoman, but her much shorter biographical sketch includes two pieces of information that Milner’s story does not. First, that Walker visited several Caribbean nations in order ‘to expand her business to other countries where people had Afro hair’ (40); this detail gives Walker a wider global significance than Milner, an American author, provided. Second, Chimbiri points out that Walker’s original difficulties with hair loss were partly due to stress. Stress is also the cause of Marietta’s hair loss in Patrice Lawrence’s short story A Bob and a Weave, written as part of New Class at Malory Towers, an update of the Enid Blyton stories. Marietta is worried about her mother, a boxer, who has been having mental and emotional difficulties since being knocked out in a fight. ‘I couldn’t stop thinking about it,’ Marietta tells another character, ‘That’s when my hair started falling out’ (37). While she initially tries to hide her hair loss with a wig, she is found out by the other girls and, eventually, encouraged to be open about her story and the physical effect it has on her.

Another recent non-fiction book, BeYoutiful (Welback, 2022), written by Shelina Janmohamed and illustrated by Chanté Timothy devotes twenty pages to hair and explores how it can be personal, cultural, political and religious. The book includes discussion of the Hijab, headwraps, racism and texturism, facial hair, and shaved heads. It features Halima Aden (the first hijabi Muslim woman on the front of Vogue magazine), Marsha Hunt (the first Black woman on the cover of England’s high fashion magazine Queen) CJ Walker, Annie Malone, Frida Kahlo, and Harnaam Kaur. Laxmi’s Mooch by Shelly Anand, illustrated by Nabi H. Ali (Kokila 2021) is a picture book published in the USA, with a multicultural cast of characters that features a young girl who is teased for having hair on her top lip. Her father tells her about Frida Kahlo and her mother explains that hair doesn’t just grow on top of our heads. Laxmi’s journey of self-acceptance impacts her school peers and the story ends with them queuing up for her to draw a ‘mooch’ on them. In Hana and The Hairy Bod Rapper (2022), written and self-published by Dr Leema Jabbar and illustrated by Pearly L, Hana studies her arm hair in the mirror. Her exclamation that ‘It’s not fair!’ is given additional resonance by the inclusion of a book about Snow White in the spread.

Another recent non-fiction book, BeYoutiful (Welback, 2022), written by Shelina Janmohamed and illustrated by Chanté Timothy devotes twenty pages to hair and explores how it can be personal, cultural, political and religious. The book includes discussion of the Hijab, headwraps, racism and texturism, facial hair, and shaved heads. It features Halima Aden (the first hijabi Muslim woman on the front of Vogue magazine), Marsha Hunt (the first Black woman on the cover of England’s high fashion magazine Queen) CJ Walker, Annie Malone, Frida Kahlo, and Harnaam Kaur. Laxmi’s Mooch by Shelly Anand, illustrated by Nabi H. Ali (Kokila 2021) is a picture book published in the USA, with a multicultural cast of characters that features a young girl who is teased for having hair on her top lip. Her father tells her about Frida Kahlo and her mother explains that hair doesn’t just grow on top of our heads. Laxmi’s journey of self-acceptance impacts her school peers and the story ends with them queuing up for her to draw a ‘mooch’ on them. In Hana and The Hairy Bod Rapper (2022), written and self-published by Dr Leema Jabbar and illustrated by Pearly L, Hana studies her arm hair in the mirror. Her exclamation that ‘It’s not fair!’ is given additional resonance by the inclusion of a book about Snow White in the spread.

In I Am Not My Hair (Black Jac 2021), Malika-Zaynah Grants illustrates six-year-old Delena Thompson’s account of being diagnosed with alopecia areata, her subsequent hair loss and her coming to terms with this with the help the love and support of her parents. The book ends with Delena being featured in Cocoa Girl magazine.

Recently one of the traditional tales most closely associated with hair has been subject to retellings. The picture book Rapunzel (Simon and  Shuster 2017) by Chloe Perkins is set in India and illustrated in a vivid style that combines traditional and contemporary aesthetics by Archana Sreenivasen, herself based in Bangalore. Rapunzel wears a sari and a long plait. Rumaysa (MacMillan 2021) by Radiya Hafiza, illustrated by Rhaida El Touny retells Rapunzel, Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty connecting the three narratives in the process. In a twist on the Rapunzel story, Rumaysa lets down her hijab. The story can thus be read as reinterpreting a European traditional tale; however, Kate Forsyth notes in The Rebirth of Rapunzel: A Mythic Biography of the Maiden in the Tower (2016) that the earliest surviving reference to a story of a maiden in a tower comes in Shahnameh by the Persian poet Ferdowsi, where Rudāba lets down her hair.

Shuster 2017) by Chloe Perkins is set in India and illustrated in a vivid style that combines traditional and contemporary aesthetics by Archana Sreenivasen, herself based in Bangalore. Rapunzel wears a sari and a long plait. Rumaysa (MacMillan 2021) by Radiya Hafiza, illustrated by Rhaida El Touny retells Rapunzel, Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty connecting the three narratives in the process. In a twist on the Rapunzel story, Rumaysa lets down her hijab. The story can thus be read as reinterpreting a European traditional tale; however, Kate Forsyth notes in The Rebirth of Rapunzel: A Mythic Biography of the Maiden in the Tower (2016) that the earliest surviving reference to a story of a maiden in a tower comes in Shahnameh by the Persian poet Ferdowsi, where Rudāba lets down her hair.

There have been a number of stories in picture book form of late that celebrate Black hair. Mira’s Curly Hair by Maryam al Serkal and Rebeca Luciani was published in the US and UK in (2019 by Lantana). My Hair, written by Hannah Lee, illustrated by Allen Fatimaharan (2019 Faber and Faber) involves a visit to the hairdressers and explores a range of Black hairstyles and hair coverings. Sofia the Dreamer and her Magical Afro written by Jessica Wilson, illustrated by Tom Rawles (2020 Tallawah) explores the African diaspora through hair, taking in Rastas, Black Panthers and Ethiopa. Your Hair is your Crown written by Jessica Dunrod, illustrated by Alexandra Tungusova (Lili Translates 2020) features a protagonist racialized as mixed, living in Wales.

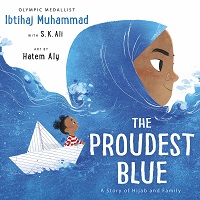

Other recent picture books look at why some people choose to cover their hair. What is a Patka? (2019,) written Tajinder Kaur Kalia and  illustrated by Yuribelle is a self-published picture book that explains in narrative form practices of hair covering in Sikhism and ends with instructions on how to tie a patka. In The Proudest Blue by Olympic medallist Ibtihaj Muhammed with S.K. Ali, art by Hatem Aly (Anderson 2020), we are offered a window into Asiya’s first day wearing a hijab, narrated by her little sister Faizah. She encounters stares, questions and taunts, but remains strong, recalling her mother’s words, ‘Don’t carry around the hurtful words that others say. Drop them. They are not yours to keep.’

illustrated by Yuribelle is a self-published picture book that explains in narrative form practices of hair covering in Sikhism and ends with instructions on how to tie a patka. In The Proudest Blue by Olympic medallist Ibtihaj Muhammed with S.K. Ali, art by Hatem Aly (Anderson 2020), we are offered a window into Asiya’s first day wearing a hijab, narrated by her little sister Faizah. She encounters stares, questions and taunts, but remains strong, recalling her mother’s words, ‘Don’t carry around the hurtful words that others say. Drop them. They are not yours to keep.’

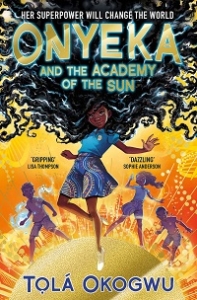

Like K.N. Chimbiri, Tọlá Okogwu began her writing career by self-publishing. The first of her Daddy Do My Hair? picture book series appeared in 2016. In Beth’s Twists, black hair is not described in dismissive language nor depicted as a challenge or something to be ‘managed’ or ‘tamed’ (with all the racialized connotations such language holds). Instead, hairstyling is showing to be fun-filled and loving. In Okugwu’s highly anticipated debut novel  Onyeka (Simon and Schuster, 2022), the title character’s hair is a source of power, strength and magic. Onyeka is a British-Nigerian girl who discovers her curls have psychokinetic abilities and is sent to the Academy of the Sun, a school in Nigeria where Solari – children with superpowers – are trained. Okugwu offers us a vision of a school where Black hair is not policed or merely tolerated – it is celebrated.

Onyeka (Simon and Schuster, 2022), the title character’s hair is a source of power, strength and magic. Onyeka is a British-Nigerian girl who discovers her curls have psychokinetic abilities and is sent to the Academy of the Sun, a school in Nigeria where Solari – children with superpowers – are trained. Okugwu offers us a vision of a school where Black hair is not policed or merely tolerated – it is celebrated.

Karen Sands-O’Connor is the British Academy Global Professor for Children’s Literature at Newcastle University. Her books include Children’s Publishing and Black Britain 1965-2015 (Palgrave Macmillan 2017).

Darren Chetty is a teacher, doctoral researcher and writer with research interests in education, philosophy, racism, children’s literature and hip hop culture. He is a contributor to The Good Immigrant, edited by Nikesh Shukla and the author, with Jeffrey Boakye, of What Is Masculinity? Why Does It Matter? And Other Big Questions. He tweets at @rapclassroom.

Books mentioned:

Anna Laetitia – Barbauld Evenings at Home (1791-6)

G.A. Henty – A Roving Commission; or, Through the Black Insurrection in Hayti (1900)

Nina Bawden On the Run (1964)

Michael Morpurgo – A Medal for Leroy (2012)

Inky Pinky Ponky (edited by Mike Rosen and Susannah Steele in 1982)

Lorraine Simeon – Marcellus (originally published in 1984)

Medeia Cohan – Hats of Faith (2017)

Denene Milner – Madam C. J. Walker Builds a Business (2019)

The Story of Afro Hair – KN Chimbiri, illustrated by Joelle Avelino (2021)

New Class at Malory Towers – Patrice Lawrence

BeYoutiful – Shelina Janmohamed, illustrated by Chanté Timothy (Welback, 2022),

Laxmi’s Mooch – Shelly Anand, illustrated by Nabi H. Ali (Kokila 2021)

I Am Not My Hair (Black Jac 2021), Malika-Zaynah Grants

Rapunzel (Simon and Shuster 2017) – Chloe Perkins, illustrated Archana Sreenivasen

Rumaysa (MacMillan 2021) – Radiya Hafiza, illustrated by Rhaida El Touny

Mira’s Curly Hair – Maryam al Serkal and Rebeca Luciani (2019 Lantana).

My Hair – Hannah Lee, illustrated by Allen Fatimaharan (2019 Faber and Faber)

Sofia the Dreamer and her Magical Afro written – Jessica Wilson, illustrated by Tom Rawles (2020 Tallawah)

Your Hair is your Crown written – Jessica Dunrod, illustrated by Alexandra Tungusova (Lili Translates 2020)

What is a Patka? (2019,) – Tajinder Kaur Kalia and illustrated by Yuribelle is a self-published

The Proudest Blue – Ibtihaj Muhammed with S.K. Ali, art by Hatem Aly (Anderson 2020)

Daddy Do My Hair: Beth’s Twists Tola Okugwu (2018)

Onyeka Tola Okugwu (Simon and Schuster, 2022)