The Language of Drawing

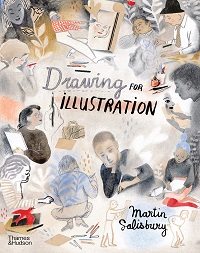

Martin Salisbury is Professor of Illustration at the Cambridge School of Art, where he founded the renowned MA Children’s Book Illustration programme. One of the world’s foremost experts on the subject of illustration, his new book Drawing for Illustration examines the ways in which the process and activity of drawing underpins, directs and supports the work of illustrators, including – of course – picture book and children’s book illustrators.

In this extract, he discusses definitions of illustration and some of the functions of those making use of it.

Drawing remains the fundamental language of the illustrator and an equally fundamental aspect of its research and preparation. In its many guises and meanings, ‘drawing’ continues to feed and underpin the output of the successful illustrative artist, even if it is not the actual method used to create the work. It is drawing, and the understanding or ‘knowing’ that it nurtures, that informs convincing illustrative image-making in all its forms.

Drawing remains the fundamental language of the illustrator and an equally fundamental aspect of its research and preparation. In its many guises and meanings, ‘drawing’ continues to feed and underpin the output of the successful illustrative artist, even if it is not the actual method used to create the work. It is drawing, and the understanding or ‘knowing’ that it nurtures, that informs convincing illustrative image-making in all its forms.

In 1962, the illustrator and painter Lynton Lamb published Drawing for Illustration with Oxford University Press. It was an important contribution to understanding of the illustrator’s art and craft at the time. Analysis of the various print processes through which illustrators’ original artworks found their way to the printed page inevitably formed a significant proportion of Lamb’s text, as did the need to be able to work to a particular scale. The requirement for illustrators of the time to have a full understanding of these processes had been of paramount importance from the invention of printing up until around the time when Lamb wrote his text. In shamelessly stealing the title of Lamb’s excellent book, I hope to further illuminate the subject in the context of today’s publishing industries, in a world much changed.

One of the difficulties inherent in using words to write or speak about drawing is the fact that, ultimately, drawing is itself a language. As the illustrator and painter John Minton pointed out: ‘For a Cézanne cannot be described, if it could there would have been no need for it to have been painted …’ The language of drawing goes beyond description. T. S. Eliot, writing about poetry rather than drawing, speculated that the chief use of ‘meaning’ in this context is often “… to satisfy one habit of the reader, to keep his mind diverted and quiet, while the poem does its work upon him: much as the imaginary burglar is always provided with a nice piece of meat for the house-dog.“ It was an idea that Marshall McLuhan was famously to develop later – “For the “content” of a medium is like the juicy piece of meat carried by the burglar to distract the watchdog of the mind” – popularly condensed into the phrase ‘the medium is the message’. There are clear parallels between the languages of poetry and drawing, each being formally subject to certain underlying mechanics or ‘grammar’, but (with the exception of purely technical or informational drawing) with ‘meaning’ being readable in a variety of ways.

When Lamb wrote Drawing for Illustration, the relationship between drawing and illustration was perhaps more straightforward. In many ways illustration was drawing. Certainly, most published illustration was executed originally in the form of ink on paper. Drawing formed the basis of teaching in the art schools of the day, in all fields of the ‘Fine’ and applied arts. For the illustrator, these acquired skills were largely employed in making visual the writer’s text, at a time when illustration was generally seen as entirely subordinate to the written word. Now, sixty years on, illustration’s connection to both formal drawing and the written word have changed considerably. Illustrators are increasingly creating their own content, as graphic novelists, picturebook-makers, documentary artists… ‘picture-writers’ if you will. The teaching of drawing in the most formal, academic sense is, however, increasingly rare. Until relatively recently it had been seen as the foundation stone of learning across all of the visual arts. Now, in the absence of such formal training, the relationship between drawing and the activity of illustration varies greatly between one illustrator and another.

The relationship between Fine Art and Illustration has itself long been a prickly one. Lamb quoted John Berger’s famous observation, ‘drawing without searching equals illustration’. Berger was referring to the most literal definition of the word ‘illustration’. But illustration has always been easy game for such put-downs, possibly more so in recent times as the fine arts have moved away from any direct relationship with formal drawing skills and has perhaps needed to find other ways to identify itself as of a higher purpose. The vacuum in drawing-based expressive art needed to be filled and this is happening through the growth in authorial visual narrative texts as practiced by a generation of expressive artist-authors such as Isabelle Arsenault, Jillian Tamaki, Shaun Tan, Isabel Greenberg, John Broadly, Jon McNaught and Brian Selznick. And, of course, the great works by children’s picturebook-makers are becoming increasingly recognised within literature and the arts.

Book illustration

The use of illustration for adult fiction, as distinct from young adult fiction, children’s book illustration or picturebook-making, is perhaps less common than it was in the past and tends to be confined primarily to the fine presses, publishers of lavishly designed and produced collectable editions such as the Folio Society in the UK and the Limited Editions Club in the US and of course young adult fiction. That said, in recent years book design and production generally has seen a noticeable surge in print and production quality, with commercial books of all categories needing to become much more desirable as tactile objects to be held and owned in order to compete with screen-based reading. Non-fiction hardback books in particular have made increasing of use of illustration, especially in fields such as nature writing, lifestyle and travel where book cover and jacket design especially have once again become boom areas for illustrators.

Illustration for fiction can be a contentious area. Commissioning an artist to add pictorial interpretations to a text that was originally conceived and written as a stand-alone experience is not always welcome. Writers and readers can sometimes feel that illustration intrudes on the reader’s imagination. But the best illustration in this field is careful to avoid duplicating or visualising literally the writer’s words. Often a more tangential approach is required, suggesting mood, background or atmosphere, creating a counterpoint to the reading of words and augmenting the overall aesthetic experience. Explicit visual depictions of moments of drama are rarely successful. Ardizzone, touched on these issues in another rare excursion into analysis in ARK, the iconic Journal of the Royal College of Art, in 1954:

The Function of an Illustrator: The illustrator has to add to the work of the author. He has to explain something to the reader which the author cannot say in words or has not the space to do so. His illustrations should form an evocative visual background to the story, a background which the reader can people with the characters of the author. The suggestion and the hint are often more important than the clear-cut statement. Don’t do too much of the reader’s work for him; rather, help him to use his imagination. Be careful of the dramatic scenes in a book. Violence and drama are often better expressed in words. It is easy to fall into the trap of being literary. The approach to illustration should be purely visual.

Character development

For illustrators working in the field of children’s books, especially picturebook-making, the creation of convincing and consistent characters is particularly important. To create characters that are absolutely believable normally demands a great deal of time spent testing them out in the sketchbook or on endless sheets of paper. Sometimes the artist may have a very clear idea in mind as to the key personality traits of the character(s). Sometimes the characters may only really assert themselves (and perhaps surprise their creator) through the process of drawing, coming to life on paper as the drawing grows in confidence.

Whichever way round the process works, it is often only when two or more characters are drawn interacting with each other that they really  begin to assert their respective identities and eventually start to dictate the development of a narrative. This is a process that I liken to the gradual maturing of a TV drama series or situation comedy. Many writers for television series have spoken of how early episodes come to be looked back on as somewhat stilted and forced as the actors try to make sense of their roles. After a period of time, they begin to better know their characters’ identities and start to ‘add on’ various mannerisms and idiosyncrasies to their roles. The writers in turn find themselves ‘writing for the characters’ as the actors increasingly contribute to establishing their identities. Consequently, the nature of the ‘situations’ that are written into the situation comedy are increasingly led by the dramatic possibilities that interactions between the contrasting personalities present.

begin to assert their respective identities and eventually start to dictate the development of a narrative. This is a process that I liken to the gradual maturing of a TV drama series or situation comedy. Many writers for television series have spoken of how early episodes come to be looked back on as somewhat stilted and forced as the actors try to make sense of their roles. After a period of time, they begin to better know their characters’ identities and start to ‘add on’ various mannerisms and idiosyncrasies to their roles. The writers in turn find themselves ‘writing for the characters’ as the actors increasingly contribute to establishing their identities. Consequently, the nature of the ‘situations’ that are written into the situation comedy are increasingly led by the dramatic possibilities that interactions between the contrasting personalities present.

Atmosphere and fantasy

The last decades of the nineteenth century and the first two decades of the twentieth were a ‘Golden Age’ for illustration. New possibilities in full-colour printing emerged, precipitating an explosion of voluptuous and imaginative watercolour illustration from the likes of Arthur Rackham, Kay Nielsen and Edmund Dulac in Europe, while in America the growth in popular magazines saw many respected figurative artists including John Sloan and William Glackens become regular and greatly admired contributors to popular publications. The richly illustrated ‘gift book’ fantasies from the likes of Rackham and Dulac during the late Victorian period have exerted a lasting influence on imaginative book illustration.

The world of fairies and wonderlands continues to engage and enthrall, and is kept alive today through the combined vision and watercolour craftsmanship of artists such as Alan Lee and P. J. Lynch. It is perhaps true to say that the convincing visualisation of fantastic worlds and mystical, mythical creatures can be at its most effective when represented in an essentially realist, idiomatic manner. Making the unreal real (if you will) demands great technical skill as well as vision.

Drawing for Illustration is published by Thames & Hudson, 978-0500023310, £30.00 hbk.