This article is in the Beyond The Secret Garden Category

Beyond the Secret Garden: Lessons from School Books

In the latest in their series examining the representation of black, Asian and minority ethnic voices in British children’s literature, Darren Chetty and Karen Sands-O’Connor go back to school.

For many children school is their first encounter with society beyond their own family. So it is no surprise that children’s books are often set in schools. From the beginning of the nineteenth century, at least some of these schools were multiracial, from the one in Charles and Mary Lamb’s poem ‘Conquest of Prejudice’ (1809) to Bessie Marchant’s The Two New Girls (1927) at boarding school. Nonetheless, it was not until the 1970s that children in British school stories regularly included racially minoritized characters. Petronella Breinburg and Errol Lloyd normalized the experience of being new to school for Black children (and other readers as well) in their landmark picture book Sean Goes to School (1973). Middle grade readers were often about finding friends, including Grace Nichols’ seven-year-old Leslyn navigating a new country and a new school at the same time in Leslyn in London (1984) or Gillian Cross’s Clipper in the humorous Save Our School series (1981-91). White teachers in books for older readers were often well-meaning, like Wordsy in Farrukh Dhondy’s short story ‘Two Kinda Truth’ (Come to Mecca 1978) or Mr. Johnson in Andrew Salkey’s Danny Jones (1980), but they rarely understood the dreams and struggles of their Black students.

For many children school is their first encounter with society beyond their own family. So it is no surprise that children’s books are often set in schools. From the beginning of the nineteenth century, at least some of these schools were multiracial, from the one in Charles and Mary Lamb’s poem ‘Conquest of Prejudice’ (1809) to Bessie Marchant’s The Two New Girls (1927) at boarding school. Nonetheless, it was not until the 1970s that children in British school stories regularly included racially minoritized characters. Petronella Breinburg and Errol Lloyd normalized the experience of being new to school for Black children (and other readers as well) in their landmark picture book Sean Goes to School (1973). Middle grade readers were often about finding friends, including Grace Nichols’ seven-year-old Leslyn navigating a new country and a new school at the same time in Leslyn in London (1984) or Gillian Cross’s Clipper in the humorous Save Our School series (1981-91). White teachers in books for older readers were often well-meaning, like Wordsy in Farrukh Dhondy’s short story ‘Two Kinda Truth’ (Come to Mecca 1978) or Mr. Johnson in Andrew Salkey’s Danny Jones (1980), but they rarely understood the dreams and struggles of their Black students.

In Hal by Jean MacGibbon (Heinemann 1974) a mixed Black girl helps a white boy to overcome his fear of school with the help of her teacher, whose progressive approach is contrasted with some of her more traditional colleagues. The story hold interest for its celebration of a multiculturalism that is very much of its time. In one episode, the children spontaneously burst into song together. A Kenyan child drums while ‘Pakistanis, Cypriots – the lot’ join in. ‘Mary Malone was dancing a jig… Only the English stood about, envious, embarrassed.’ The use of cultural stereotypes – including that of the English as repressed or lacking a culture of their own – captures the limitations of a form of multicultural education that Barry Troyna was to criticise as the 3s of ‘saris, steelpans, and samosas’. Tony Drake subtly critiques stereotypes in Playing It Right (Puffin 1979) when cricket coach Mr Bunting observes Nirmal bowl ‘dead slow and dead straight’ only to hear the headteacher from another school comment ‘Crafty spinners these Indians, you know’ (68).

The schools portrayed in these books were generally urban, non-fee-paying, and realistically portrayed. Only the occasional school story with characters from racially minoritized backgrounds includes fantastic elements; Robert Leeson’s Third Class Genie (1975), for example, uses the Black characters, a genie and a bully, to force the white protagonist to see things from others’ perspectives.

While many contemporary school stories include similar themes, the range of stories and mix of genres in more recent books marks a  noticeable change. For the youngest readers, focus has shifted away from first day fears and toward achievement and activity. Books like Pamela Venus’s Let’s Go to Playgroup (Firetree 2016) or Anna McQuinn and Rosalind Beardshaw’s Lulu’s First Day (Alanna Max 2019) depict happy, confident children enjoying school and taking charge of choosing their activities. In Tender Earth by Sita Brahmachari (Macmillan 2017), Mrs Latif, who is described as wearing a headscarf, leads her multiracial class in philosophical conversation that informs some of protagonist Laila’s decision making.

noticeable change. For the youngest readers, focus has shifted away from first day fears and toward achievement and activity. Books like Pamela Venus’s Let’s Go to Playgroup (Firetree 2016) or Anna McQuinn and Rosalind Beardshaw’s Lulu’s First Day (Alanna Max 2019) depict happy, confident children enjoying school and taking charge of choosing their activities. In Tender Earth by Sita Brahmachari (Macmillan 2017), Mrs Latif, who is described as wearing a headscarf, leads her multiracial class in philosophical conversation that informs some of protagonist Laila’s decision making.

While stories of racism continue to appear, we detect a shift towards emphasizing the agency of racially minoritised students as they resist hostility and institutional racism. In the opening of That Asian Kid by Savita Kalhan (Troika 2019), Jeevan hears his teacher describe a complaint against her as ‘one of the boys… playing the race cards because he doesn’t like his grades.’(p7) Jeevan’s journey is one of self-discovery and self-assertion. In Muhammad Khan’s Mark My Words (Macmillan 2022), school student Dua Iqbal’s investigative journalism uncovers the class and race-based scapegoating at her school. In Fight Back (Scholastic 2022), A.M Dassu shows school as a potentially hostile environment for many students, while also portraying school students as having independence of mind and a commitment to change things for the better. Aaliyah leads a broad coalition of students (as seen on the book’s cover) to protest the banning of religious symbols in the school.

The traditional British boarding school story has only occasionally included children of racially-minoritised backgrounds, and the most famous recent example of the genre, J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter, has faced both criticism and fan reinvention. Sarah Park Dahlen and Ebony Elizabeth Thomas have called for critics, scholars and readers to ‘assess Rowling’s record on race, justice, and difference and . . . come to an informed decision about what diversity in the wizarding world of Harry Potter will mean going forward’ (Harry Potter and the Other 8). Harry Potter is not the only series that has undergone fan and author revision. Enid Blyton’s Mallory Towers, first published in the 1940s and 1950s, were reissued by Hachette with revisions for ‘sensitivity reasons’, according to their website; Hachette also commissioned new stories with Black and Asian characters in New Class at Mallory Towers (2019). Patrice Lawrence, who wrote one of the new Mallory Towers stories, said she did it to make the books ‘relevant for a whole new audience’ (‘I want to write books that have hope in them’: Patrice Lawrence on tackling heavy themes with light | BookTrust). Beyond rewrites, the boarding school story continues to be reinvented—perhaps because it provides readers in the 9-14 age group a way to ‘grow up’ through books, using familiar devices and plots to keep readers comfortable as they experience new aspects of the school story. Robin Stevens’ Murder Most Unladylike series (Puffin 2014-2021) has Hong Kong-born character, Hazel Wong, solving crimes at an English boarding school in the 1930s with white British Daisy Wells.

Schools feature in a number of recent books set in countries beyond the UK. Shiko Nguru’s Mwikali and the Forbidden Mask (Lantana 2022) uses tropes of the school story-outsider character trying to fit into a new school and find friends – to introduce readers both to Kenyan traditions, language and culture (the story is set in an exclusive Nairobi school) and to time- and space-travel fantasy. The school in Nguru’s story both anchors the reader in the familiar and provides the source of danger, as the teachers are not all they seem, and Mwikali must learn to harness her power to defeat them and make school safe for everyone. Puneet Bhandal’s Starlet Rivals (Lantana 2022) is the first in the Bollywood Academy stories, taking a familiar plot (young ingenue scholarship student experiences rivalry with character representing the establishment) but setting it in India’s exciting Bollywood atmosphere. In Onyeka and The Academy of the Sun by Tọlá Okogwu, The Academy is not only described in terms of the powers of the Solari who train there; it is well-resourced with elite standard sports facilities, and with an emphasis on sustainability, such as food production.

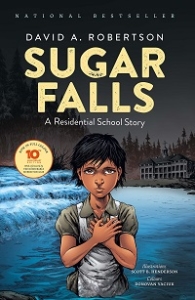

Canada has recently seen the publication of a number of stories based on historical events concerning ‘Residential Schools’ and their devasting impact on First Nation peoples. Picture books such as When We Were Alone by David A. Robertson and Julie Flett (Highwater 2016) and I Am Not a Number, written by Jenny Kay Dupais and Kathy Kacer, and illustrated by Gillian Newland (2016 Second Story) offer age-appropriate accounts of the inhumanity inflicted on First Nation people by the Canadian school system. Sugar Falls by David A. Robertson and Scott B. Henderson (Highwater 2012/ 2021) is a graphic novel telling the true story of Betty Ross, Elder from Cross Lake First Nation. While many fictional stories depict schools as the site where a new, better society is created, these historical stories remind us that in reality schools have often been sites of social division and inequality.

Canada has recently seen the publication of a number of stories based on historical events concerning ‘Residential Schools’ and their devasting impact on First Nation peoples. Picture books such as When We Were Alone by David A. Robertson and Julie Flett (Highwater 2016) and I Am Not a Number, written by Jenny Kay Dupais and Kathy Kacer, and illustrated by Gillian Newland (2016 Second Story) offer age-appropriate accounts of the inhumanity inflicted on First Nation people by the Canadian school system. Sugar Falls by David A. Robertson and Scott B. Henderson (Highwater 2012/ 2021) is a graphic novel telling the true story of Betty Ross, Elder from Cross Lake First Nation. While many fictional stories depict schools as the site where a new, better society is created, these historical stories remind us that in reality schools have often been sites of social division and inequality.

Karen Sands-O’Connor is the British Academy Global Professor for Children’s Literature at Newcastle University. Her books include Children’s Publishing and Black Britain 1965-2015 (Palgrave Macmillan 2017).

Darren Chetty is a teacher, doctoral researcher and writer with research interests in education, philosophy, racism, children’s literature and hip-hop culture. He is a contributor to The Good Immigrant, edited by Nikesh Shukla and the author, with Jeffrey Boakye, of What Is Masculinity? Why Does It Matter? And Other Big Questions. He tweets at @rapclassroom.

Books Mentioned

Two New Girls Bessie Marchant (1927)

Sean Goes to School Petronella Breinburg and Errol Lloyd (1973)

Leslyn in London Grace Nichols (1984)

Save Our School Gillian Cross (1981)

Come to Mecca Farrukh Dhondy (1978)

Danny Jones Andrew Salkey (1980)

Hal Jean MacGibbon (1974)

Playing it Right Tony Drake (1979)

Third Class Genie Robert Leeson (1975)

Let’s Go to Playgroup Pamela Venus (2016)

Lulu’s First Day Anna McQuinn and Rosalind Beardshaw (2019)

Tender Earth Sita Brahmachari (2017)

That Asian Kid Savita Kalhan (2019)

Mark My Words Muhammad Khan (2022)

Fight Back A.M. Dassu (2022)

Murder Most Unladylike Robin Stevens (2014)

Mwikali and the Forbidden Mask Shiko Nguru (2022)

Starlet Rivals Puneet Bhandal (2022)

Onyeka and The Academy of the Sun Tọlá Okogwu (2022)

When We Were Alone David A. Robertson and Julie Flett (2016)

I Am Not a Number Jenny Kay Dupais & Kathy Kacer, Gillian Newland (2016)

Sugar Falls by David A. Robertson & Scott B. Henderson (2012/ 2021)