Tyger, tyger: An interview with SF Said

SF Said is the author of Varjak Paw, winner of the 2003 Smarties Prize; The Outlaw Varjak Paw, 2007 Blue Peter Book of the Year; Phoenix, shortlisted for the Guardian Children’s Fiction Prize 2016; and his newest novel, Tyger, all illustrated by Dave McKean and published by David Fickling Books. Imogen Russell Williams interviewed SF Said for Books for Keeps.

SF Said is the author of Varjak Paw, winner of the 2003 Smarties Prize; The Outlaw Varjak Paw, 2007 Blue Peter Book of the Year; Phoenix, shortlisted for the Guardian Children’s Fiction Prize 2016; and his newest novel, Tyger, all illustrated by Dave McKean and published by David Fickling Books. Imogen Russell Williams interviewed SF Said for Books for Keeps.

Tyger is set in an alternate Britain in which the Empire never fell and slavery was never outlawed, in a London where foreigners must live in the Soho Ghetto and are treated with suspicion and contempt. Adam Alhambra lives in the ghetto with his family, keeping his head down and obeying the rules, but one day he encounters a creature of mythic power and beauty – a celestial Tyger, who has been wounded and is hiding from a terrifying adversary. With the help of his friend Zadie, can Adam help her find safety – and help reshape his stricken, oppressive world as he does so?

During your career as a children’s writer you’ve moved from cat to human (and superhuman) protagonists, but this is the first time that you’ve had a Muslim main character. Can you tell me a bit about where Adam came from?

Well, Adam comes very much from me. His identity is a lot like my identity – he’s a British Muslim of Middle Eastern origin. When I started out writing children’s books in 1997, I just didn’t really feel that [a story like mine] was a story you could tell, or that anybody would want to publish. So I wrote [Varjak Paw], a story about a Mesopotamian Blue cat. Mesopotamia, of course, is the ancient name of the country we now call Iraq, where some of my family originally came from – but I came to live in London when I was two, and I have no memory of living anywhere else. Like Adam, I grew up in London, having this almost mythical history and background that I gradually learned more about as I went on, and when I was younger, there were many times that that felt like something of a burden. Identities like mine were quite unusual in Britain in the 1970s, and there were times I experienced things you wouldn’t want anybody to experience. Adam’s troubles in his world – it’s a lot of stuff I’ve lived through.

So Adam perceiving his own heritage as a burden, but also something that’s part of who he is and how he came to be – all that is drawing on your own experience?

Yes, very much. When I was a kid, as I say, there weren’t a lot of other kids of Muslim or Middle Eastern background around me, and there  certainly weren’t a lot of children’s books that dealt with my kind of identity. The only one I can think of is Watership Down by Richard Adams, in which, it seemed to me, although this was a book about rabbits, there was a great deal of what looks like Arabic, and particularly the name of the great hero of the rabbit mythology, El-ahrairah. That’s not real Arabic, but it looks an awful lot like it, and it was stunning to me, as an eight-year-old reading Watership Down, to see that the greatest rabbit who ever lived, in what was clearly the best book ever written, had an Arabic name like mine. And it was probably the first moment I can remember in which I thought, perhaps Arab and Islamic history and culture and civilization were not some kind of shameful baggage, but were things I could be proud of, because here they were, celebrated in the greatest book ever. Now, in 2022, 50 years after the publication of Watership Down, we seem to be in a moment where publishers are much more open to this kind of story.

certainly weren’t a lot of children’s books that dealt with my kind of identity. The only one I can think of is Watership Down by Richard Adams, in which, it seemed to me, although this was a book about rabbits, there was a great deal of what looks like Arabic, and particularly the name of the great hero of the rabbit mythology, El-ahrairah. That’s not real Arabic, but it looks an awful lot like it, and it was stunning to me, as an eight-year-old reading Watership Down, to see that the greatest rabbit who ever lived, in what was clearly the best book ever written, had an Arabic name like mine. And it was probably the first moment I can remember in which I thought, perhaps Arab and Islamic history and culture and civilization were not some kind of shameful baggage, but were things I could be proud of, because here they were, celebrated in the greatest book ever. Now, in 2022, 50 years after the publication of Watership Down, we seem to be in a moment where publishers are much more open to this kind of story.

All your books are political, but this is your most overtly political book – the idea of class division is explicit in your lords, commoners and slaves, and of course, you deal squarely with the subject of empire. What’s drawn you in this direction?

In a way, I think the politics are the same politics. Varjak [Paw’s] family think they’re very special pedigree cats; they look down on street cats, and then all cats look down on dogs as stinking noisy monsters. I really don’t think that’s all that different to what’s going on in Tyger, except I’m, as you say, explicitly saying, here are some Muslim characters, here are lords, here are slaves, and this is happening in London, and it’s the 21st century. But it’s an alternate world; it’s not our world. I think that’s what allowed me to do that. And I’ve always wanted to write an alternate world story – I particularly love Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials and Malorie Blackman’s Noughts and Crosses. They were my two great lodestars, while writing Tyger – that you can do that, you can imagine history any way you want.

But then there’s also what’s been happening. Between 2013 and 2022 we’ve had Brexit, we’ve had Donald Trump, we’ve had no end of situations of polarisation, where what I would call ‘us and them’ politics has come to dominate and divide. And I hate that. I resist it with everything I’ve got. I believe that the things that unite us are far greater than those that divide us. Difference is real – we can’t pretend it’s not – but it is something to be embraced and celebrated, a source of richness. It’s not something to be feared. And I think by the time I finished writing Tyger, it seemed more important than ever to put out into the world a book that talks about that, and that perhaps had space for everyone in it. I think that was my highest aim. To my mind, it’s a classic children’s book adventure that absolutely everybody, of any age from nine up, could read and enjoy and fall in love with. But I would be particularly thrilled if Muslim kids were to see in it something of what I saw in Watership Down and El-ahrairah – that “I too could be the hero of this adventure.” Whatever it is you dream of doing, you can do it; the way the world is is not the way it has to be.

As well as being a gorgeous adventure, Tyger has some powerful, shocking moments – like the scene at Tyburn when a boy of colour is hanged for the ‘crime’ of being a runaway slave, and both Adam and the reader hope desperately for a miraculous rescue that doesn’t materialise. Did you have any qualms about showing that so directly?

Of course. Absolutely. I thought long and hard about it, but that is the world they’re in, and that was the world here, not long ago. Public executions at Tyburn continued shockingly late; runaway slaves who perhaps may not even have been runaway slaves were executed at Tyburn. You know, it happened. It’s part and parcel of a system of oppression and prejudice that you can see manifested in lots of other ways. And I decided in the end, it had to be there – you had to see it – because this is the naked truth of that world exposed. That scene upsets me too. But sometimes I think if a book deals with something difficult, it’s not really being truthful if it doesn’t show what’s actually involved. If you have slavery, then you have to show that a slave’s life is worth nothing; it’s an object that can be disposed of. Literature of any sort, but especially children’s literature, has an obligation to be truthful.

Of course. Absolutely. I thought long and hard about it, but that is the world they’re in, and that was the world here, not long ago. Public executions at Tyburn continued shockingly late; runaway slaves who perhaps may not even have been runaway slaves were executed at Tyburn. You know, it happened. It’s part and parcel of a system of oppression and prejudice that you can see manifested in lots of other ways. And I decided in the end, it had to be there – you had to see it – because this is the naked truth of that world exposed. That scene upsets me too. But sometimes I think if a book deals with something difficult, it’s not really being truthful if it doesn’t show what’s actually involved. If you have slavery, then you have to show that a slave’s life is worth nothing; it’s an object that can be disposed of. Literature of any sort, but especially children’s literature, has an obligation to be truthful.

What made you choose London for the setting, and Soho for the ghetto where foreigners have to live?

Well, I’ve always wanted to write a London book. I’ve read a lot of books set in London, I’ve seen a lot of films set in London, and none of them, to me really captured the London that I know, which can be a place of appalling violence and pollution and horror, but can also be a place of extraordinary openness. I love what Sadiq Khan said about London being open to everyone – I believe it is. That’s the whole essence of London. I love the fact that you can hear every language in the world spoken on London streets, you can eat every kind of food from around the world. So I wanted to put my London into a book. As for Soho – we could talk about the history of Soho as a place that historically was where immigrants, outsiders of various sorts, found a home. There are streets with names like Poland Street for a very good reason. But when the phrase “the Soho Ghetto” came into my mind I was like – “no, that’s it. There’s got to be a Soho Ghetto.” It’s just right. You know, sometimes with writing you mean to do a thing and you do it consciously, and sometimes something just clicks in your head. [laughs] Sometimes my decisions come down to poetry.

The influence of Blake is clear – especially in your title! – and you’ve mentioned Philip Pullman and Malorie Blackman as lodestars of alternate worlds. What other influences shaped Tyger as you went along?

Oh, so many. Yes, William Blake – both his work, which I read a lot, and his life – he’s a very big one. Alf Layla wa-Layla (known in English as the Arabian Nights), that’s another. Alan Garner, along with other writers of that era, such as Ursula le Guin, Susan Cooper – the sorts of writers who take ancient mythology and make something new from it, bring it into a contemporary setting. I feel like that is very much the project in Tyger: the mythic and the real meeting. Watership Down does that as well; there’s the mythic story, El-ahrairah, and there’s Hazel, and they meet at the very end, though what I like is them criss-crossing throughout. Also, in Tyger, she is very much a tiger, and I did a lot of research into actual tigers. I even went to ZSL [London Zoo], where the keeper of the large mammals, Teague Stubbington – his actual name! – allowed me in a tiger cage. The tiger fortunately wasn’t there at the time, but the smell of the tyger, that is described in the book like honeysuckle growing wild – that is what it smelled like, that’s solid research. It’s factual!

You’ve talked about the lengthy process of writing Tyger. Why do you think it took you nine years?

I think the main reason why it took me so long is I’m just not that good at making things compulsively readable. I have to work quite a lot at it. But it’s the thing I want the most. I want my stuff to feel like it’s reading itself, like it’s not an effort at all. It should not feel literary or highbrow in any way; it should feel like a page-turning adventure you can’t put down. And until it feels like that. I don’t feel it’s done. The one good thing about that, from my point of view – there are a lot of bad things, the bad things being largely economic! – but the good thing about it is that over the course of that time, I feel you get a depth and a density, a clarity that I’m not sure you can get any other way. I look at somebody like Alan Garner and I think his books do have that quality of enormous depth, enormous clarity – and he takes about a decade a book. I think of Alan Garner as being the patron saint of slow writers. If Alan Garner can take a decade over a book, it’s okay, because every single book Alan Garner has done is a great book. Every single one of them is worth reading. They’re all brilliant, they’re all unique, and nobody else could possibly have written them.

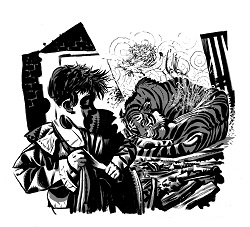

In your longstanding partnership with Dave McKean, words and pictures work together phenomenally well – especially having just seen all the illustrations in the finished book! Was anything different about Tyger? Or was it done as you’ve always worked together?

I think our working relationship has evolved over the years. With Varjak Paw…essentially, the process on that book was I gave him a Word  document, and it came back looking like Varjak Paw. I can take absolutely no credit for anything in the illustration and design at all. It’s all Dave. But as time went by, we started to work together… All the time I was working on Tyger, I was gathering material, which I then presented to him at the end. Then we had a conversation about the thoughts and ideas, and he began to work. So I would say it’s a collaboration now in a way it wasn’t at the beginning.

document, and it came back looking like Varjak Paw. I can take absolutely no credit for anything in the illustration and design at all. It’s all Dave. But as time went by, we started to work together… All the time I was working on Tyger, I was gathering material, which I then presented to him at the end. Then we had a conversation about the thoughts and ideas, and he began to work. So I would say it’s a collaboration now in a way it wasn’t at the beginning.

For instance, we talked about an artist called Frans Masereel, who did an amazing book called The City. I think it’s from the 1920s or 30s, and it might be Berlin or Vienna. It’s a sort of woodblock style, absolutely beautiful. That was a big source of inspiration for the way the city scenes look. They’re quite blocky, they’re quite angular, they’re quite rigid and a little bit oppressive and crammed in, because that’s how we wanted you to feel in the city scenes. But the scenes where Adam is with the tyger, everything is a lot more organic, it’s a lot more fluid. And there we were talking about a bunch of other references: Edmund Dulac, Kay Nielsen, Aubrey Beardsley – all quite old stuff, like classic children’s book illustration from maybe 100 years ago; the glory days of the illustrated gift book. One really important thing about Tyger is that both myself and Dave, and DFB, wanted it to be a beautiful object, and something that was a tactile pleasure, that had all kinds of bits you could discover. So the endpapers, the actual hardback behind the dust jacket, you know, even the pages at the front with the Tyger’s footprints, everything should be taking you into the world of Tyger, and then bringing you out again at the end. I feel as a physical object, that it’s really, really beautiful, both visually and in tactile terms.

Lastly, in Tyger, Adam and Zadie must open not just the doors of perception, but a whole series of doors to save their world from the cruelty and pollution that threatens to kill it. Is there still hope for us to open our doors?

Yes, of course, there’s always hope. I think there are there are all sorts of reasons to be hopeful. To me, the very fact that there is now space in the world for a book like Tyger where there wasn’t 20 years ago [is hopeful]. There are dark forces, but actually, what I think of as forces of light are stronger and more vocal than they were, too. We don’t know where things are going. There are times I feel extremely doomy and apocalyptic. But there are times I’m extraordinarily moved and inspired to see the work that people are doing to build a better world. And that starts, for me, with children and the books they read, and the stories that fill their imaginations – the work I see teachers, librarians, booksellers, reading helpers, journalists, readers of all sorts, doing – there’s a lot of people working very, very hard, every single day, to inspire kids to love reading and books, and to get them the best possible books, the widest range, the most diverse, inclusive kinds of books, so that every child could see themselves reflected, so that every child can feel they could be a reader.

I’m not somebody who has children myself, but I feel that, with everybody who reads one of my books, I’m having a conversation with them. I’m trying to pass on everything that I think is important, everything I care about. When I read Watership Down at the age of eight, I saw an exciting adventure about rabbits; a kid reading Tyger now will probably see an exciting adventure about a tiger. When I reread Watership Down as an adult, I saw that it was about the big questions of our lives: who are we? Where do we come from? Where do we belong? How should we live? I hope my books are the kinds of books that one could return to at different ages and find other layers or the levels of meaning that might repay a lifetime’s reading. (Maybe that’s another reason why they take a long time to write.)

Imogen Russell Williams is an author and a journalist and editorial consultant specialising in children’s literature and YA.

Tyger by SF Said, illustrated by Dave McKean, is published by David Fickling Books, 978-1788452830, £12.99 hbk.