Valediction No.1: Forbidding mourning

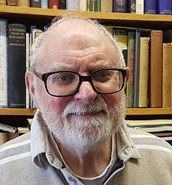

Say farewell to Classics in Short, says Brian Alderson. They are over; let them go.

They arrived in the printed BfK 102 of January 1997 when Helen Levene visited Treasure Island and set up the paragraph form that has continued over the last twenty-five years with myself taking over at no.13 after Helen had bagged all the most fruity titles. I can’t say that the continuation will be missed since not one of my 136 efforts has generated any praise or, more surprisingly, blame. One asks if Jack Hawkins and co. have anything to say today that is relevant to twenty-first century social and intellectual persuasions.

They arrived in the printed BfK 102 of January 1997 when Helen Levene visited Treasure Island and set up the paragraph form that has continued over the last twenty-five years with myself taking over at no.13 after Helen had bagged all the most fruity titles. I can’t say that the continuation will be missed since not one of my 136 efforts has generated any praise or, more surprisingly, blame. One asks if Jack Hawkins and co. have anything to say today that is relevant to twenty-first century social and intellectual persuasions.

But the back page does not get rid of me that easily and the Valediction entered upon here is of an altogether personal nature. It so happens that a year or two ago I offered my collection of children’s books to Newcastle upon Tyne (of which fair city I am a Freeman) with the post-1920 copies going to Seven Stories and the earlier books to the Children’s Literature Unit of the University where they are housed in the Philip Robinson Library.

It makes for a grievous parting – books no more for keeps. I love them greatly (well, some of them) and in saying good-bye to them I have decided to write some notes not on the Classics but on obscure titles which few these days will have heard of but which deserve a glance if anyone happens by.

So let’s talk about Golf.

Bernard Darwin (1876-1961) was the grandson of the great Charles and was brought up at Down House after the death of his mother two days after he was born. He did not follow his grandpa into beetles however but showed an early proclivity for golf and became a famous amateur and an even more famous writer on the subject.

He had, however, married Elinor Monsell from Ireland, a wood engraver and artist some of whose work was done for W.B.Yeats at the Abbey Theatre. (After coming to England she also did the two colour plates for De la Mare’s Three Mulla-Mulgars which the publisher forgot to acknowledge.)

The Darwin family was though a tribe of geniuses (Elinor would later introduce Bernard’s cousin Gwen to the craft of wood engraving of which, as Gwen Raverat, she was to become one of the greatest practitioners.) And Gwen’s sister Margaret was to become the wife of Geoffrey Keynes: surgeon, medical historian, book collector, authority on William Blake, and editor, especially associated with Francis Meynell’s private publishing venture, the Nonesuch Press.

It is not known if Keynes or Meynell were keen on golf and it may well have been Margaret who suggested to Bernard that he might take a holiday from the subject and write a book for children that Elinor might illustrate and the Nonesuch Press publish, and thus it was that Mr Tootleoo came sailing into the Christmas market of 1925. (He was not much of a sailor, being shipwrecked at the start of his story when he is found drifting among the waves sitting in his own hat.)

Bernard engages his readers in ballad form:

Now listen while I tell to you

The tale of Mr Tootleoo…

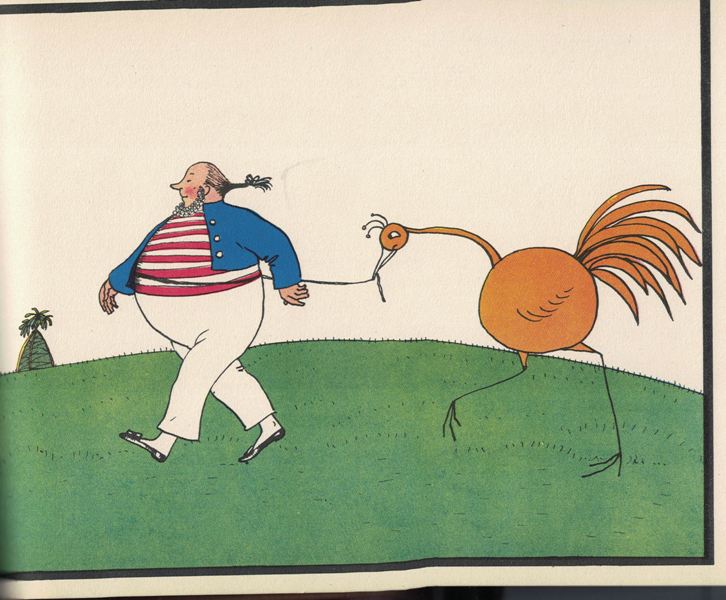

and the twenty-two pages of his text are faced by Elinor’s handsomely printed full-page colour lithographs.

The whole thing is an exercise in absurdity with Mr T being saved by a family of Cockyollybirds. With ballad-maker’s devices they are transformed to a mother and her six children and all ends happily with everyone dancing on a hospitable desert island. (Mr T’s proposal to the lady cockollybird, now transformed and in a crinoline, having been accepted.)

The book – very elaborate for its time – was a success and reprinted the following January and a sequel, Tootleoo Two, came out in 1927 (the children did not care for schooling and return to Cockyolly form). The stories flickered on when Nonesuch produced the two together in a cheap edition of upright format with the drawings remodelled in black and white. In 1935 the burgeoning Faber & Faber persuaded Mr T to take to the sea again with Mr Tootleoo and Co. but despite printing from the Curwen Press the journey was less successful. Nor can much be said of Bernard’s three vaguely oriental fairy tales Oboli, Boboli, and Little Joboli (1938). This was published by Country Life where Bernard was Golf Correspondent and he may have been persuaded to do it by their children’s books editor, Noel Carrington who put out a soft-back edition in 1942.

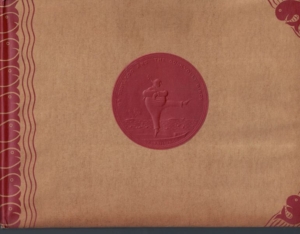

Description: The Tale of Mr Tootleoo. By Bernard and Elinor Darwin. London: The Nonesuch Press [1925]. 195x260mm. [92]pp. incl. 22 lithographs in four colours. Dec Simili vellum over boards with an imitation circular wax medallion to front centre with an embossed image after the illustration on p.5, plain white endpapers. Pale green dj, with circular excision to show medallion.

Ref. McKitterick History 43

Titles printed bold, here and in successor valedictions, are part of the gift to Seven Stories.

Brian Alderson is a long-time and much-valued contributor to Books for Keeps, founder of the Children’s Books History Society and a former Children’s Books Editor for The Times. His book The 100 Best Children’s Books is published by Galileo Publishing, 978-1903385982, £14.99 hbk.

Brian Alderson is a long-time and much-valued contributor to Books for Keeps, founder of the Children’s Books History Society and a former Children’s Books Editor for The Times. His book The 100 Best Children’s Books is published by Galileo Publishing, 978-1903385982, £14.99 hbk.