This article is in the Beyond The Secret Garden Category

Beyond the Secret Garden: Reading Joyfully

In the latest in our long-running Beyond the Secret Garden series, Darren Chetty and Karen Sands-O’Connor take a critical look at joy in children’s books.

The phrase ‘childhood joy’ often goes with words like ‘pure’ and ‘unadulterated’. But joy as depicted in children’s literature is almost always adulterated—written by adults. This means that joy in children’s books can often fall into adult nostalgia for what they see as the simple and stress-free life of the child. In some classic children’s texts, joy is quashed by adults, and any adults that are joyful are depicted as childlike. J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan (1911) is an example of this; the Darling children’s mother tidies their minds at night and is most alarmed by the idea of the joyful freedom to do whatever you choose embodied in Peter Pan. Joy is depicted as amoral, if not immoral, and the Darling children must ultimately reject it. If they don’t, they risk turning into the kind of adults who live in eternal childhood with Peter, pirates and Barrie’s made-up Indian tribe, named after a racial slur and described as ‘savages’ and animal-like. This negative linking of childhood joy with people of colour is not unique to Peter Pan; many British children’s books have historically described adults of colour who find ‘childlike’ joy in new clothing, food, and music as figures of ridicule, or examples for (white) readers to avoid.

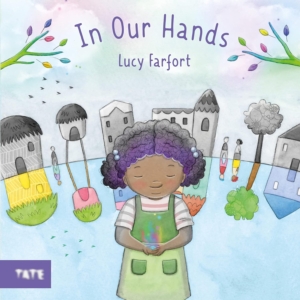

But the critical attitude toward joy found in these children’s books belies the fact that joy, whether for children or for people of colour, is rarely simple or self-absorbed. Joy in a new outfit or a good meal is more intense if it is a rare occurrence; playing music brings joy through the hard work of creativity and through the way that it connects the musician to others. A good example of the joy that results from the hard work and cooperation of children is Lucy Farfort’s In Our Hands (2022). In Farfort’s imagined world, colour disappears, and with it joy disappears also: ‘people felt sad and angry’ and ‘Hurt replaced harmony’. The opposite of joy, in Farfort’s book, is indifference: ‘When the last drop of colour finally left our planet, the people in charge shrugged their shoulders and said nothing could be done’. Adults give up; but the unnamed child protagonist of Farfort’s story looks for joy – she is shown peering through a telescope. She finds a seed, but a seed is not enough to change a planet. She must nurture the seed, not alone, but with other children, who use their creativity (some play music to the small tree, for example) to help it grow until ‘Bit by joyful bit’ their energy, creativity and hard work pay off and colour returns to the planet.

But the critical attitude toward joy found in these children’s books belies the fact that joy, whether for children or for people of colour, is rarely simple or self-absorbed. Joy in a new outfit or a good meal is more intense if it is a rare occurrence; playing music brings joy through the hard work of creativity and through the way that it connects the musician to others. A good example of the joy that results from the hard work and cooperation of children is Lucy Farfort’s In Our Hands (2022). In Farfort’s imagined world, colour disappears, and with it joy disappears also: ‘people felt sad and angry’ and ‘Hurt replaced harmony’. The opposite of joy, in Farfort’s book, is indifference: ‘When the last drop of colour finally left our planet, the people in charge shrugged their shoulders and said nothing could be done’. Adults give up; but the unnamed child protagonist of Farfort’s story looks for joy – she is shown peering through a telescope. She finds a seed, but a seed is not enough to change a planet. She must nurture the seed, not alone, but with other children, who use their creativity (some play music to the small tree, for example) to help it grow until ‘Bit by joyful bit’ their energy, creativity and hard work pay off and colour returns to the planet.

Similarly, Varsha Shah’s Ajay and the Mumbai Sun (2020) depicts a group of young people who find joy in working together to achieve a goal: putting out a newspaper written and produced by themselves. Ajay, Saif, Vinod, Yasmin and Jai are from Mumbai’s slums, and often have to struggle to find enough to eat—but the book is about joy rather than the misery of poverty. The book is full of joyful words: grinning, happy, jubilant, celebration—almost all of which are connected to the creative energies of the child protagonists. When the first edition of their newspaper appears, ‘Ajay had never felt as happy in his life’ (58). When Saif sees a way to use his engineering skills to help the others get information for a story, he is described as ‘looking as if all his birthday and Christmas presents had come at once’ (206). The child characters in Shah’s books find joy in their own ability to make change happen, and (as in Lucy Farfort’s book), their joyous activism comes despite adult indifference and lack of faith in their abilities.

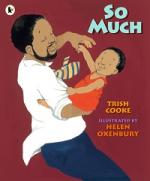

Joy does not always have to result from hard work in children’s books, but it is often connected with the end of a period of waiting. The two  most common joyful depictions in children’s books are new babies and holiday celebrations. Trish Cooke’s now-classic So Much (1994), with pictures by Helen Oxenbury, shows an entire extended family who come together to celebrate the new baby. The waiting in this book is not about the baby, but waiting for the baby’s father, whose birthday it is, to arrive. However, the baby is the centre of the narrative, and because of the baby the house is full of music and play, dancing, music, and food for adults and children alike, all of whom have smiles on their faces.

most common joyful depictions in children’s books are new babies and holiday celebrations. Trish Cooke’s now-classic So Much (1994), with pictures by Helen Oxenbury, shows an entire extended family who come together to celebrate the new baby. The waiting in this book is not about the baby, but waiting for the baby’s father, whose birthday it is, to arrive. However, the baby is the centre of the narrative, and because of the baby the house is full of music and play, dancing, music, and food for adults and children alike, all of whom have smiles on their faces.

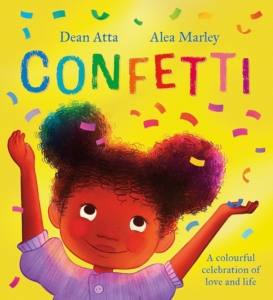

Dean Atta and Alea Marley’s Confetti (2024), similarly combines two periods of waiting (for the new baby to arrive and for a wedding) that lead to growing joy for the main character, Arianna. The book starts with a single piece of confetti that Arianna finds under a sofa, which triggers a happy memory of her third birthday; after she finds it, she begins to look for confetti—the symbol of joy—in everything from falling leaves to fireworks, as well as the birth of her baby sister, a Pride parade, and wedding of her uncle. Joy, Atta and Marley suggest, can be big or small but is always worth looking for.

Dean Atta and Alea Marley’s Confetti (2024), similarly combines two periods of waiting (for the new baby to arrive and for a wedding) that lead to growing joy for the main character, Arianna. The book starts with a single piece of confetti that Arianna finds under a sofa, which triggers a happy memory of her third birthday; after she finds it, she begins to look for confetti—the symbol of joy—in everything from falling leaves to fireworks, as well as the birth of her baby sister, a Pride parade, and wedding of her uncle. Joy, Atta and Marley suggest, can be big or small but is always worth looking for.

In Jump Up (2022), written and illustrated by Ken Wilson-Max, Cecille experiences the joy of celebration at Carnival. It is a joy that connects her to her family history, as she sleeps and dreams of her mother’s village. The information provided at the back of the back helps readers to understand how Carnival is at once joyful, playful and political in nature.

A number of recent series have also foregrounded racially minoritised children experiencing joy and proved to be commercially successful. Zanib Mian, a former Little Rebels Award Winner, and winner at the inaugural Inclusive Books for Children Awards last month, is now well into her second series of books that foreground fun and joy with Muslim protagonists. Mian followed up the Planet Omar series with the Meet the Maliks series. Rashmi Sirdeshpande and Diane Ewen’s series of picture books beginning with Never Show a T-Rex a Book (2020) introduces us to a Black child at the centre of dinosaur-related madcap fun.

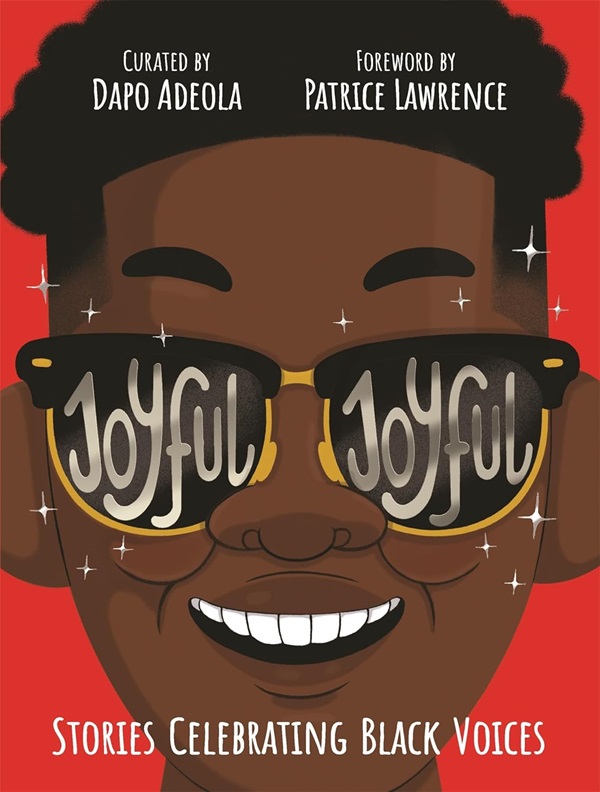

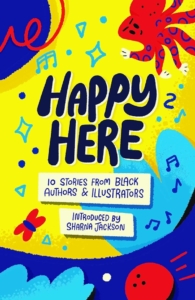

Joy, particularly Black joy has been the focus of three recent anthologies. Happy Here (2021) published by Knights Of brings together ten  Black writers and ten Black illustrators. In the opening story A House Like No Other, written by Alexis Sheppard and illustrated by Dorcas Magbadelo, Izzy travels from her town where her she and her white mum are often stared at and where she can’t buy her favourite hardo bread, to visit her great Aunt V in Brixton. Izzy finds joy and confidence while there. Sheppard subverts a popular trope in British children’s literature; that adventure is to be found when one escapes the city for the countryside, suggesting that there is joy to be found in the city and in a sense of community. Curated by Jamie Wilson and Jade Orlando, full colour hardback A Year of Black Joy: 52 Black Voices Share Their Life Passions (2023) includes among others Michelle Ogundehin, Lady Phyll, and Sheku Kanneh-Mason. Topics include ‘the joy of habitats’, the joy of wheelchair racing’, and ‘the joy of democracy’. Political dimensions of Black people’s lives are not omitted, but joy is foregrounded throughout. Joyful Joyful (2022), curated by British Book Awards Illustrator of the Year Dapo Adeloa features twenty-two writers each paired with an illustrator. Patrice Lawrence’s foreword begins with, ‘In the last two years, I have almost managed to convince myself that there is no joy in the world.’ In his introduction, Adeola writes that he ‘wanted to create something that I wish had been available to me as a young reader’. Both statements offer context for the urgency for joy in books featuring Black characters.

Black writers and ten Black illustrators. In the opening story A House Like No Other, written by Alexis Sheppard and illustrated by Dorcas Magbadelo, Izzy travels from her town where her she and her white mum are often stared at and where she can’t buy her favourite hardo bread, to visit her great Aunt V in Brixton. Izzy finds joy and confidence while there. Sheppard subverts a popular trope in British children’s literature; that adventure is to be found when one escapes the city for the countryside, suggesting that there is joy to be found in the city and in a sense of community. Curated by Jamie Wilson and Jade Orlando, full colour hardback A Year of Black Joy: 52 Black Voices Share Their Life Passions (2023) includes among others Michelle Ogundehin, Lady Phyll, and Sheku Kanneh-Mason. Topics include ‘the joy of habitats’, the joy of wheelchair racing’, and ‘the joy of democracy’. Political dimensions of Black people’s lives are not omitted, but joy is foregrounded throughout. Joyful Joyful (2022), curated by British Book Awards Illustrator of the Year Dapo Adeloa features twenty-two writers each paired with an illustrator. Patrice Lawrence’s foreword begins with, ‘In the last two years, I have almost managed to convince myself that there is no joy in the world.’ In his introduction, Adeola writes that he ‘wanted to create something that I wish had been available to me as a young reader’. Both statements offer context for the urgency for joy in books featuring Black characters.

Karen Sands-O’Connor is the British Academy Global Professor for Children’s Literature Newcastle University. Her books include Children’s Publishing and Black Britain 1965-2015 (Palgrave Macmillan 2017).

Darren Chetty is a teacher, doctoral researcher and writer with research interests in education, philosophy, racism, children’s literature and hip-hop culture. He is a contributor to The Good Immigrant, edited by Nikesh Shukla, and the author, with Jeffrey Boakye, of What Is Masculinity? Why Does It Matter? And Other Big Questions. He tweets at @rapclassroom.

Books mentioned:

In Our Hands, Lucy Farfort, Tate Publishing, 978-1849768146, £7.99 pbk

Ajay and the Mumbai Sun, Varsha Shah, Chicken House, 978-1913696337, £7.99 pbk

So Much, Trish Cooke, illus Helen Oxenbury, Walker Books, 978-1406390728, £8.99 pbk

Confetti, Dean Atta, illus Alea Marley, Orchard Books, 978-1408362075, £12.99 hbk

Planet Omar, Zainab Mian, illus Nasaya Mafaridik, Hodder Children’s Books, 978-1444951226, £6.99 pbk

Meet the Maliks, Zainab Mian, Hodder Children’s Books, 978-1444923674, £6.99 pbk

Never Show a T-Rex a Book, Rashmi Sirdeshpande, illus Diane Ewen, Puffin, 978-0241392669, £7.99 pbk

Happy Here, various, Knights Of, 978-1913311162, £6.99 pbk

A Year of Black Joy: 52 Black Voices Share Their Life Passions, edited Jamie Wilson and Jade Orlando, Magic Cat Publishing, 978-1915569028, £14.99 hbk

Joyful, Joyful, curated by Dapo Adeola, Two Hoots, 978-1529071504, £20.00 hbk