A Q&A Interview with Sam Thompson

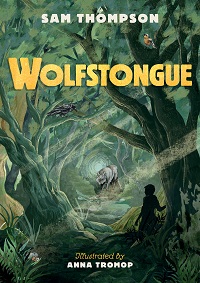

Highly praised for his adult novels, Sam Thompson turns his hand to writing for children in Wolfstongue, an unsettling, serious fable full of talking animals, hidden places and intriguing ideas. He answered our questions about it.

Can you tell us a bit about the inspiration for Wolfstongue? Where did the idea start?

For me, ideas often start when two inspirations collide. In the case of Wolfstongue, one of my children was having trouble with his speech, and I wanted to write something that would help him make sense of that challenge; he also loved wolves. I had a feeling that there was a connection between the wolves and the words, but I wasn’t sure what it was. To find out, I wrote the story of Silas, who cannot find the words he needs but discovers that there is a hidden world where animals speak.

Talking animals are a favourite motif in children’s books. Do you have favourites, and how did you apply that to your book?

It seems to be natural for humans to imagine animals talking – we’ve been putting words in their mouths since the very beginnings of storytelling. I have so many favourites, from The Jungle Book and The Wind in the Willows to The Rats of NIMH and Varjak Paw… One talking animal tale that was especially important for Wolfstongue isn’t a children’s book but a medieval cycle of beast fables called Reynard the Fox, in which the trickster Reynard is always talking himself into and out of trouble with the other animals, including his arch-rival Isengrim the Wolf. Yes, animals who can speak are a familiar feature of children’s stories, but it’s a strange idea when you think about it. I wanted to explore that strangeness, and remind readers of how strange it is that there really is an animal who talks — it’s us.

You explore ideas of the power of language. Why did you decide to do that, and what do you want children to understand?

I’m very preoccupied with those ideas. I can’t think of a more important topic, or one that’s closer to home. Language has such power to help and to hurt, whether in our most private experiences or in the way the human species imposes itself on the planet. I hope the wolves and foxes of Wolfstongue offer readers a myth about the good and bad we can do when we name one another and tell stories about one another — and not just one another, because when we tell tales about the sly fox and the big bad wolf, we turn other living beings into symbols for aspects of ourselves, and human stories end up shaping the non-human world.

I also hope Wolfstongue has comfort to offer readers in their own struggles with words. Perhaps it’s comforting to remember that there is a world beyond language, and to imagine how we could inhabit that silence in the company of wolves.

This is your first book for children. What do you enjoy most about writing for young people, and what do you think are the challenges?

In all the important respects, the challenges are the same whoever you’re writing for: finding the story that needs to be told and telling it as simply and clearly as you can. What I enjoy about writing for young people is that there’s an extra urgency about it. I remember being a young reader, the hunger for books, the need to absorb what was inside them and be changed by it. It’s serious business.

Do you plan to write more books for children?

I’m working on a sequel to Wolfstongue at the moment. When I finished the book I found that I’d uncovered the beginnings of another story, so I’m digging deeper…

You teach creative writing. What do you think is the single most important piece of advice for anyone who wants to write?

Just to keep going. Persistence is more important than anything. You’re in a hurry, and often it feels as if you’re getting nowhere; but if you want to do it, keep doing it, and eventually you’ll get to where you did not expect.

Wolfstongue, by Sam Thompson, illustrated by Anna Tromop, is published by Little Island, £8.99 pbk