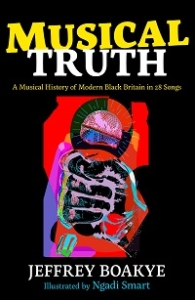

Musical Truth: An Interview with Jeffrey Boakye

Darren Chetty interviews his friend and sometime writing partner Jeffrey Boakye about his book Musical Truth.

Jeffrey Boakye is a special talent and Musical Truth is a special book. It manages to cover more Black British post-war history than my entire education from primary school to university. And it does so in prose that is energetic, funny and crafted so as to appear effortless. So, when Books for Keeps asked me if I’d interview him, I jumped at the chance. I began by asking Jeffrey how he went about selecting the 28 songs for Musical Truth.

‘I tried not to over think it. I wanted to represent various eras of the black British narrative and knit them together into something cohesive, so I knew I wanted a spread of songs spanning various decades. But beyond that, it wasn’t too calculated. I started with songs that have impacted upon my life in some personal or significant way – songs that I have grown with or represent particular moments in my personal development. Naturally, that’s a big list. So, it just became a process of selecting the songs that said something important about the wider black British experience. That said, these had to be songs that I felt I could comment on. It wasn’t just a case of choosing the most politically or historically relevant songs and using them to tell a basic history. It was also important for me to ensure that the songs were representative of the spectrum of styles that black music encompasses. I was keen to let the playlist go broad into a range of genres.’

Jeffrey and I first met through the UK HipHopEd Seminars that we both had a hand in organising. These sessions brought teachers, artists, youth-workers and scholars together to explore the relationship between education and hip hop culture. Karl Nova, winner of the 2018 CLiPPA award was another person I first met there who has since gone on to write for children. Jeffrey was a star presenter at these sessions; more than once someone was heard to say ‘I wish he’d been my English teacher at school.’ How does hip hop inform his work?

‘Hip hop taught me that the expression of skill in the face of wider adversity is a powerful driving force, and teaching is, I feel, all about empowering people out of becoming victims of wider society. Hip hop doesn’t back down. Add it all up and it’s safe to say that my writing and my teaching exemplifies the creativity and criticality that you see a in hip hop mindset. Or at least, that’s what I’m aiming for anyway.’

The DJ – knowledgeable, in control and yet sensitive to their audience – is also how Boakye talks about his approach to both teaching and writing for a young audience. I was lucky enough to read an early draft of Jeffrey’s first book Hold Tight (Influx) which explored grime and Black masculinity using a track-by-track format. Since then, Boakye has written the critically acclaimed Black, Listed (Dialogue). He and I together wrote What Is Masculinity? (Wayland) for children and young adults. I’m not claiming to be a disinterested party when I write about Jeffrey. And Jeffrey is not claiming to be a disinterested party when he writes about Black British history – and nor should he.

The DJ – knowledgeable, in control and yet sensitive to their audience – is also how Boakye talks about his approach to both teaching and writing for a young audience. I was lucky enough to read an early draft of Jeffrey’s first book Hold Tight (Influx) which explored grime and Black masculinity using a track-by-track format. Since then, Boakye has written the critically acclaimed Black, Listed (Dialogue). He and I together wrote What Is Masculinity? (Wayland) for children and young adults. I’m not claiming to be a disinterested party when I write about Jeffrey. And Jeffrey is not claiming to be a disinterested party when he writes about Black British history – and nor should he.

‘Black history didn’t come into the picture in my formal education. It’s a scary fact that everything I’ve learned of black history beyond a thin explanation of the American Civil Rights Movement, I’ve found out for myself, or been exposed to outside of school. I never went to any formal supplementary schools out anything, but there was a whole curriculum being taught to me through black culture at home, via family and friends, and also in non-mainstream media. Then, as I got older, I pursued my own curiosity by reading around the subject and making connections with people with similar interests. This is where the concept of community is so important – that network of people from whom you can learn and grow. It took work. I had to go out of my way to find things out about my own blackness, motivated by the blunt realities of growing up black in a white world.”

In my own work with schools on developing an antiracist, inclusive ethos I have been recommending Musical Truth alongside books by David Olusoga, Hakim Adi, Dan Lyndon, and Kandace Chimbiri. All these books are excellent in offering accessible approaches to information that has too often been withheld from young people in British schools. But whilst these other books apply a fairly traditional children’s non-fiction authorial style to Black British history, Boakye writes in a more personal style very popular in adult narrative non-fiction but less common in children’s books. ‘I literally start the book with Hello…My name is Jeffrey,’ he points out. We talk about how this voice comes out of Jeffrey’s approach to teaching. This more personal approach to writing allows him to discuss what particular historical events mean to him but also to acknowledge that he doesn’t hold all the answers. I tell Jeffrey that his narrative voice in Musical Truth – he describes it as ‘breaking the fourth wall when narrating painful events’ – reminded me most of EH Gombrich’s classic A Little History of The World (Yale), a book first published in 1935. Yet, I couldn’t think of many non-fiction books for younger readers since that had taken a similar tone, at once authoritative, warm and humble.

‘I hadn’t seen a template for that ever and I really thought hard about audience… So, if it’s something which is traumatic, rather than trying to put the shields up and intellectualize it and kind of be confident with it, I’d drop the shields even more and say this is difficult, this is hard in there are no easy answers here. If there are no easy answers, I’m going to say that.’

We talk about how many of the textbooks we read as school-kids didn’t even have an author’s name on the front. ‘It comes from this place of nebulous sort of authority’ and how difficult this disembodied authority was to challenge when we were school kids reading stereotypical, and often racist, views of the world.

Musical Truth deserves to be read widely by young people. Although the book is aimed at Key Stage 3 students, I’d say that teachers from Year 3 upwards will find the book useful for lessons and as a very accessible way to begin building their own background knowledge. Jeffrey is not stopping here, however.

‘My next book, I Heard What You Said, has a keen focus on race in the British education system. I’m proud of this one. It’s been difficult to write – but it’s so important in exploring how race is dealt with (or not) in British schools.’

Darren Chetty is a teacher, doctoral researcher and writer with research interests in education, philosophy, racism, children’s literature and hip hop culture. He is a contributor to The Good Immigrant, edited by Nikesh Shukla and the author, with Jeffrey Boakye, of What Is Masculinity? Why Does It Matter? And Other Big Questions. With Karen Sands-O’Connor, he writes the Beyond the Secret Garden column for Books for Keeps. He tweets at @rapclassroom

Musical Truth: A Musical History of Modern Black Britain in 28 Songs is published by Faber and Faber, 978-0571366484, £12.99 hbk.