Authorgraph No.244: Kevin Crossley-Holland

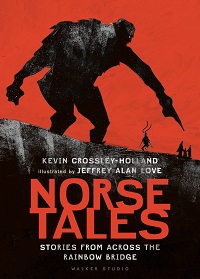

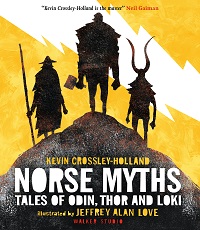

Kevin Crossley-Holland is an award-winning novelist, poet and storyteller, an expert in traditional tales and an acclaimed writer of historical fiction and retellings of legends and myths. He won the Carnegie Medal with his novella Storm in 1985, and the Guardian Children’s Fiction Prize in 2001 with The Seeing Stone, the first volume of his Arthur trilogy. His recent work includes Between Worlds, retellings of British and Irish folktales, and Norse Myths, illustrated by Jeffrey Alan Love. His latest book, a second volume of Norse tales, Stories from Across the Rainbow Bridge, has just been published by Walker.

As Gatty, one of your most memorable heroines, points out, ‘…inside our story…there are bits and pieces of all kinds of other stories.’ What’s the first story you can remember being shaped by?

I suppose that most of us can remember bits and pieces of stories, rather than hearing or reading them whole. In my case, it was certainly hearing – sleeping in my bunk bed, in the top half, with my sister Sally in the bottom half, and my father coming with his Welsh harp, sitting by our bunk beds, and singing and saying folktales to us, above all the Celtic folktales that he especially loved. And I think it was the stories of transformations that got me by the throat, and that I kept asking him to tell me again – the tale of the seal-woman who is captured by a fisherman and comes to land and bears children by him and is caught in a desperate quandary when she is empowered to go back to sea again… I think that those stories of transformation were the ones that first began to speak to me.

[As a child], I read very little. The first book I did read, hook line and sinker, and revisited so often that it came off its hinges – and became unhinged – was Our Island Story by H.E. Marshall. Terrible, chauvinistic stories, tremendously well told. And that was the first book I decided to write – a history of England, which I began when I was nine. Before I decided it was a dead loss, I wrote 77 pages.

Your second volume of Norse tales, Stories from Across the Rainbow Bridge, has just been published – and you’ve retold the Norse myths at other times too. What’s the appeal of these particular stories for you – their perennial pull?

I think I’ve become more aware, now, than when I first engaged with the Norse myths in the 1980s, of the moral ambiguity of the myths; and certainly more aware of their apocalyptic nature, so that they sing in tune with many of the thoughts and fears that we all have about the way that the world is rushing to its end, and we’re doing precious little to prevent it. They also have a splendid seam of wit, and some extremely well-defined characters, whom we follow through a series of adventures. But it has its master card in the shape of Loki, the trickster, who is like yeast; without him, the stories wouldn’t really develop, and start, middle and end would be much of a muchness. He has his transition, another transformation, from a sort of tease to the architect of the evil that has the globe crumbling – and he is the figure who promotes and enables change within those stories. It’s a tremendous body of material, and it’s been thrilling to revisit it. And I certainly don’t mean to stop yet – unless Time stops me.

Jeffrey Alan Love’s stark illustrations combine so harmoniously with your text, both in Rainbow Bridge and in the first book – and you’ve had a lot of other brilliant illustrators over the years. What do you think illustration can lend a book?

What Sendak wrote is that illustration should be ‘an expansion of the text. It’s your version of the text as an illustrator, your interpretation. It’s why you are an active partner in the book, and not a mere echo of the author.’ And Richard Strauss, or his librettist, said something like ‘Ton und Wort sind Bruder und Schwester’ – ‘Brother and sister are word and music’. Are word and image brother and sister? Yes, in a sense – but brother and sister don’t always agree, and they can often offer a varying approach to something (although kids, of course, are the first to pick up if there’s an actual discrepancy between the two disciplines.)

What Sendak wrote is that illustration should be ‘an expansion of the text. It’s your version of the text as an illustrator, your interpretation. It’s why you are an active partner in the book, and not a mere echo of the author.’ And Richard Strauss, or his librettist, said something like ‘Ton und Wort sind Bruder und Schwester’ – ‘Brother and sister are word and music’. Are word and image brother and sister? Yes, in a sense – but brother and sister don’t always agree, and they can often offer a varying approach to something (although kids, of course, are the first to pick up if there’s an actual discrepancy between the two disciplines.)

What I love best is when there’s a bouncing of the ball between the two artists, as with Jane Ray [with whom Crossley-Holland collaborated on Heartsong] We each made a journey to Venice, and we fed each other bits and pieces, images and paragraphs – and so the whole time we were exalting one another, moderating one another, qualifying. It was lovely, a real collaboration.

As well as Norse tales, you’re preoccupied with British folktales. Selkies and green children, wild men, shapeshifters who live between one form and another, liminal creatures … Why, again, do you think we return to these stories? What keeps them green, for us and for you?

It’s perhaps the dichotomy of being between having a very powerful sense of home – which has exercised me more than ever, during these strange seasons – and what ‘home’ consists of, what ‘belonging’ consists of. Is it people, place, memory? We’re caught up at the minute at a time when there have never been so many people on the go, and lost – notably, of course, refugees, but an extraordinary movement of people. And an extraordinary awareness of the movement of people, voluntary or enforced, at other times – like slaves being driven out of Africa. So the whole area of belonging, boundaries – it’s something that’s in the air, the whole time, for all of us. And I love engaging with that area, because it’s part of our story, as inhabitants in England. I think too that one thing many people have done during this virus, apart from tend their gardens, is to become more interested in relationships, more interested in their place, their community. “Who am I? How do I belong here?”

Would you say that it’s Norfolk and East Anglia that have inspired you most, geographically speaking?

I would. I would. It’s a place constantly in flux and so land and ocean are at one another the whole time…You have only to wander out into any of the fields around here, knowing something of the old field names, to pick up bits of pot, if you’re lucky an old coin; someone a couple of years ago found a wonderful Anglo-Saxon ninth century belt-buckle. The stories are here, around us, at our feet, in the air; the salt-marsh, like all empty places, becomes a theatre for stories, and superstitions; the black dog Shuck, who is called Hooter in Warwickshire and Skriker in north Lancashire – he’s not peculiar to Norfolk, but everyone here knows about Shuck, and knows to beware of him. It’s suffused, lively with stories.

Particularly when you write historical fiction, you have a unique combination of soaring poetry and visceral, down-to-earth realism. Is it difficult to decide how much detail is appropriate for young readers?

It was Edith Nesbit, I think, who said that the only way to be a good writer for children was to remember what you thought and felt and what your interests and dislikes and so on were when you were a child. I think you must not lose touch with that, and that’s something I’ve always been pretty good at – I’ve felt my own childhood, I’ve been in touch with my own childhood very vividly and continuously. On the other hand, society changes, and I have to recognise the world that children are living in now, as opposed to the world that I grew up in. One of the things that genuinely exercises me is whether I’m sufficiently in touch with kids now – not only the way they speak and think, but the society they’re growing up in, to offer a subtle, artful account of the story I want to tell, that is au courant with where children are now. At about-to-be-eighty, is the stamina, the imaginative energy still there?

You’re working on a new piece of historical fiction at the moment – can you tell me a bit about that?

It’s called Kata and Tor, and it will be set during the weeks leading up to the battle of Stamford Bridge. It will be part love-story – but not too much love! – between a Viking boy who is the illegitimate son of Harald Hardrada, and a Yorkshire girl. It’s sort of half-sister, half-brother to my two Viking novels, Bracelet of Bones and Scramasax, but it’s a standalone novel. I’m longing to get on to the North York moors and see when Hardrada turned his back on the delights of Scarborough and Bridlington and forged his way across to York. Very often it’s the land, the truth in the lie of the land, that gives me a hell of a kick. And I love writing about the relationship between place and people.

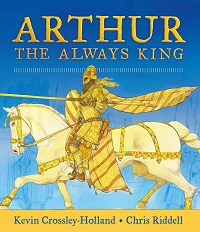

And you’ve also revisited Arthurian legend again – this time the territory of Arthur’s childhood and early youth. What drew you back to Arthur?

[In the Arthur trilogy], the legends that I chose were expressly to anticipate or recollect aspects of Arthur de Caldicot’s life; and quite often I just told bits and pieces of them, or told them very briefly. So I asked myself, after all…he was the Pan-European hero – but what are the story steps of Arthur? And I devised a very simple structure by which Arthur moves from being the first amongst equals in a brotherhood, to the rituals and rapid of romantic love, to the always uncertain and unpredictable presence of magic, to spiritual love, and so on. I devised that structure, and I preceded it with a much fuller account of Arthur’s childhood in the borders of Devon and Cornwall, when I really just let go, and let it flow. I think they’re perhaps quite good, those first two chapters, although you never know… And it’s called Arthur, The Always King.

[In the Arthur trilogy], the legends that I chose were expressly to anticipate or recollect aspects of Arthur de Caldicot’s life; and quite often I just told bits and pieces of them, or told them very briefly. So I asked myself, after all…he was the Pan-European hero – but what are the story steps of Arthur? And I devised a very simple structure by which Arthur moves from being the first amongst equals in a brotherhood, to the rituals and rapid of romantic love, to the always uncertain and unpredictable presence of magic, to spiritual love, and so on. I devised that structure, and I preceded it with a much fuller account of Arthur’s childhood in the borders of Devon and Cornwall, when I really just let go, and let it flow. I think they’re perhaps quite good, those first two chapters, although you never know… And it’s called Arthur, The Always King.

Imogen Russell Williams is a journalist and editorial consultant specialising in children’s literature and YA.

Stories from Across the Rainbow Bridge, by Kevin Crossley-Holland, illustrated by Jeffrey Alan Love, is published by Walker Books, 978-1406391763, £16.99 hbk