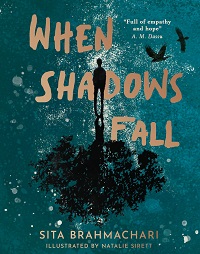

Authorgraph No.254: Sita Brahmachari

As the critically acclaimed When Shadows Fall comes out in paperback, Damian Kelleher meets author Sita Brahmachari to discover how her work is inspiring others.

It’s a bright spring day when I meet Sita Brahmachari at Waterlow Park in north London to talk about her latest book When Shadows Fall. We’ve not met before, but as soon as we sit on a park bench perched beside the beautiful gardens, Sita takes out a small box and passes me a package.

It’s a bright spring day when I meet Sita Brahmachari at Waterlow Park in north London to talk about her latest book When Shadows Fall. We’ve not met before, but as soon as we sit on a park bench perched beside the beautiful gardens, Sita takes out a small box and passes me a package.

‘I’ve got a present for you.’

It’s a piece of charcoal, a few centimetres long. And for anyone who has read When Shadows Fall and admired Natalie’s Sirett’s vivid and expressive art, the significance of the charcoal is not wasted.

‘When I go into schools to talk about the book, I start by talking about Natalie’s work,’ Sita explains. ‘I get them to hold the charcoal in their hands, and see it start to rub off.’

As the charcoal makes it mark on her audience’s hands, the creative magic begins to happen.

‘I get them to write individual poems, starting with “I’m holding charcoal in my hands”,’ explains Sita. ‘And then we see what comes.’

The launch for the hardback edition of When Shadows Falls was held in the library of Kensington Aldridge Academy, a school that stands metres from Grenfell Tower in west London. Several pupils from the school were victims of the blaze that engulfed the block in June 2017.

‘It was spine-tingling. The young people there completely understood what holding the charcoal in their hands meant.’

In the poem that prefaces her book, Sita writes about ‘the passing of a pen and charcoal to make art from scorched earth.’

In the poem that prefaces her book, Sita writes about ‘the passing of a pen and charcoal to make art from scorched earth.’

‘Without any explanation, they knew what it meant. There we were in the shadow of Grenfell, and as soon as I started speaking about the themes of the book, they just knew what I was talking about.’

When Shadows Fall focuses on the struggles of teenage Kai and his group of friends as they hang out together on a threatened patch of  wilderness in a dangerous city scape. When Kai struggles with grief, the story begins to grow in all kinds of directions. But always at its heart are the many young people in society who ‘walk this earth in the shadows’, the disadvantaged kids who grow up on the edges of society. Facing mental health challenges, exclusion from school, and social injustice, the story is relayed through a mixture of narrative, free verse and Natalie Sirett’s arresting imagery.

wilderness in a dangerous city scape. When Kai struggles with grief, the story begins to grow in all kinds of directions. But always at its heart are the many young people in society who ‘walk this earth in the shadows’, the disadvantaged kids who grow up on the edges of society. Facing mental health challenges, exclusion from school, and social injustice, the story is relayed through a mixture of narrative, free verse and Natalie Sirett’s arresting imagery.

‘The threads of this story go back so far,’ explains Sita. ‘I worked in community and youth theatre for a long time before I started writing novels. That’s why this book is a big, emotional novel for me. I did shed quite a few tears at my desk over writing this book.’

Fresh out of university, Sita started her career as a community theatre worker for the Royal Court Youth Theatre in west London.

‘I loved that title! One of the places I was asked to work in was a pupil referral unit underneath Trellick Tower, not far from Grenfell. What I saw was the damage that a lack of trust can bring about; the feeling that nobody really has your back, and the impact that can have on young people.’

These then are the beginnings of the book which Sita has described as ‘a life’s journey’.

‘It’s been written in many phases over many years. In a funny sort of way, the fragmentation of the story opened something up. For me as a writer, there’s a lot of space in the story: there’s space for image.’

What that space allowed was an opportunity for Sita to work with Sirett whom she had first met many years earlier when their children were at nursery school together.

‘We’ve been wanting to work together and waiting for the right project. We were talking about creativity and education and sketching out the ideas of it way back. I said then, ‘if I ever get this book published it will be image, and it will be word, and it will be poetry, it will be prose, song – however these young people need to express themselves.’

Publishers Little Tiger also understood the unique origins of the book. ‘They have done an amazing job,’ says Sita. ‘Mattie Whitehead and Ruth Bennett, the editors, met Natalie and said “we’re going to leave the dramatic form of the book to you.” For example, the section where we see Kai moving through London and over the bridges – it was written like a stage instruction. Natalie took that and brought so much more to the work as so many illustrators do, working closely with the designer Charlie Moyler.’

Once the book was written, illustrated and published, the story continued to grow in all sorts of creative directions – beyond even Sita’s imagination.

‘Natalie is now working on a beautiful exhibition called the Raven Treasure which we’re taking up to the Edinburgh festival. It’s going to be a kind of performance – there’s a raven treasure box made by her father-in-law Burt who’s a carpenter in his late 90s and it’s based on the box in the Rijksmuseum. It unfolds and she’s going to paint it, and as we open up the drawers we’re going to talk not just about the creation of the book, but also the creative process. She’s making it at the moment and I can’t wait to see it.’

The ravens reference an integral part of the story. Not the best-loved birds in the animal kingdom, they are often seen as a nuisance and a threat. ‘I’ve actually always loved them,’ says Sita. ‘I was obsessed with ravens growing up. I always noticed their iridescence – like a rainbow – and I loved that. One of the themes of the book is also the number of Black and mixed-race young people who are excluded from the education system in our country. The young people in this story feel as if they’re on the outside, and ravens are often shooed out of places.’

Throughout Sita’s body of work – and there are award-winning novels, short stories and plays – humanity and the natural world are recurrent themes skilfully woven throughout the plot. Green spaces are not just picturesque backdrops but provide her protagonists with vital room to breathe and grow. I ask Sita if this is inspired by her own childhood.

‘We moved around a lot but the countryside that really got under my author skin is the Lake District. The Lake District that I grew up in – I wrote about it in Kite Spirit – fed me completely. I was free in nature, able to make up stories. But when you grow up in a landscape that’s as awesome as the Lake District and you see the weather go across the fells – it changes so quickly. You are so connected with that internal Wordsworthian idea – “emotion recollected in tranquillity” – and I seek that for my city dwelling characters.

‘One in three young people in cities, and of that the most disenfranchised young people, has no access to nature. For me, mental health and the natural world have been recurrent themes in my stories. But this landscape that these young people are on, this Rec, it’s just become very real. It could be anywhere – in the banlieues of Paris for example, or in any cosmopolitan, multi-cultural city that is experiencing the massive frictions of the world and the refugee crises of many different countries.’

Working with refugees is something that Sita understands only too well. As writer in residence at the Islington Centre for Refugees and Migrants, she has direct experience of the treatment refugees receive when they arrive in the UK. She is particularly concerned about the latest announcements that the government intends to send refugees to Rwanda.

‘Everybody who is displaced – and particularly the children – needs to be treated respectfully. I’ve always wanted my stories with refugee character representation to show a journey – a journey of integration and one of opportunity. To hear now about this Rwandan…’ She pauses to try and find the right word. ‘I can’t even call it a plan. I think it’s a stunt. To use people in that way is inhumane and shameful.

‘There’s a big refrain in this book. Omid says, “when shadows fall, you stand beside.” I do think we are living in that time when it is for all of us to decide who we stand beside.’

There’s so much to talk about with this book, I say, it is so rich in themes. It takes us off in so many new directions and down so many paths. Sita agrees.

‘I said what this book doesn’t need is me talking about it!’ She laughs. ‘This is the book that spans the arc of my writing for children. The artwork that is coming through, inspired by the book, is unbelievable. There’s going to be an exhibition organised by Counterpoint Arts. I also met Love Ssega [the musician/artist] through an event I did with the National Literacy Trust, and he read my book and came back saying how much it links to his own work, campaigning for access to green spaces for young people. He’s going to be at the paperback launch and is talking about writing a song for Omid. And now we have the audiobook read by Baba Oyejide, one of the actors in Top Boy. When I listen to the audiobook I’m never tempted to read the book in my own voice – I just want to hear it read by Baba.

‘There’s even film interest, too. But I just want to see When Shadows Fall in the hands of young artists now. It’s inspiring poetry, art and song. It’s a creative catalyst.’

Damian Kelleher is a writer and journalist specialising in children’s books.

When Shadows Fall by Sita Brahmachari, illustrated by Natalie Sirett, is published by Little Tiger.